4 The English Renaissance

Timeline:

Elizabethan Theatre – named after Queen Elizabeth I (1558- 1603), House of Tudor

Jacobean Theatre – named after King James I (1603-1625), House of Stuart

Caroline Theatre – named after King Charles I (1625- 1649), House of Stuart

England had somewhat of a late start to the Renaissance, mostly due to the ongoing wars within the island and in France. On top of that, famines and plagues played a large role as well. In short, the focus was primarily on surviving, quite literally- rather than developing new trends in the arts.

It is only with the beginning of the House of Tudor – with King Henry VII in 1485 – that the cultural environment starts to change. Many scholars believe this happened because of the influence of continental humanists, such as Erasmus, who traveled to England, and because classic literature was finally available in translation at the two main universities, Cambridge and Oxford. Universities fostered and promoted Humanism in the arts and theatrical performances happening on campus. Productions were student-led, some of them were in Latin, while others were in English.

Yet, it was really during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign (1558-1603) that theatre in England experienced the greatest growth, which later continued under the two following kings, James I and Charles I, up until 1642, when the Puritans took control (eventually killing Charles I in 1649), and banned any theatrical activity for the next eighteen years.

Back in Queen Elizabeth’s London, the humanist ideals were promoted in the Inns of Court, institutions that provided further education to young men, mostly Oxford and Cambridge graduates. The curriculum focused on law, politics, and economics, and yet a strong emphasis was devoted to the arts, including classic literature and theatre. These institutions targeted wealthier students, who also constituted the intended audience of any cultural and theatrical event.

In other words, it was culture for the elite, not for the masses.

More popular theatrical events and performances were still available, although they still echoed the structure and the fashion of Medieval entertainment.

Most Inns were in the financial district, the most famous ones being The Inner Temple, the Middle Temple, The Grey’s Inn, and the Lincolns’ Inn.

The Inns housed theatrical performances all throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries and shared other theatrical spaces, such as the public theatres and the private theatres (more on those later).

Warning! Nowadays, the term “Inn” is normally associated with guest houses or pub-like businesses. That was not the case at the time.

It is at one of those Inns, the Inner Temple, that in 1561 Gorboduc (also known as Ferrex and Porrex), the first English tragedy in blank verse, was produced. The play was written by Tomas Sackville and Thomas Norton. The plot was rooted in English history, and its style echoed Seneca’s tragedies – so, very grim. All the main characters eventually die a bloody death, which is supposed to teach a lesson about the importance of securing a line of succession to the throne. For today’s aesthetic, this play would be a hard watch. It is long, very wordy, and has many characters that add complexity to the plot. At the time, it was a huge success and set the standard for a whole generation of playwrights.

As playwrights and actors understood the potential of live performances, they felt the need to widen their audience. In order to see that happen, they slightly changed their approach to storytelling with the new goal of making it more compelling and easier to follow.

The University Wits, a group of learned men primarily active in academia, worked in this direction. The most famous among them were John Lyly (1554-1606), Thomas Kyd (1558-1594), Robert Greene (1560-1592), and Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593).

Lyly’s interest focused on comedies and pastoral plays, sourcing his material from classic mythology and English history. His style was refined and almost fairytale-like. His works appealed to the aristocracy.

Kyd more strongly embraced Seneca’s subject matters and stylistic elements, such as ghosts, the chorus, and soliloquies.

Greene leaned towards romantic comedies featuring strong female characters.

Marlowe is without a doubt the most famous of the group. His Doctor Faustus continues to be successfully produced today and was seminal in defining a style and a character that would later appear in many other forms of narratives.

Marlowe writes more psychologically complex characters who face extraordinary circumstances. He is also one of the first playwrights to introduce the episodic plot, where the timeline of the play does not follow a cause-and-effect chain of events.

Some of his plays include the above-mentioned The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Tamburlaine (Parts 1 and 2), and The Jew of Malta. Most of his plays were produced by the Admiral’s Men.

His life was unfortunately cut short in 1593. Many scholars believe he would have rivaled Shakespeare if he hadn’t been killed.

As theatre grew in popularity, it soon became clear to the government, and to the monarchy specifically, that it needed to be regulated or, better still, kept under control. Even before the Tudors, actors needed the support and the employment of a gentleman, functioning as a sponsor, to perform and travel. Without said support, they would be persecuted as vagabonds. Gentlemen would employ a troupe of actors to have exclusive access to their entertainment and plays, but once they no longer needed them, they would allow the troupe to tour. A sponsor would provide actors with a small allowance and often donate their discarded clothes to be used as costumes.

When Queen Elizabeth I took the throne, she had to address a huge growth in the number of theatre troupes, most of which were misusing their patronage and producing plays whose content undermined the stability of her reign and of the church. Hence, she instituted that only local public officials, appointed by the monarchy, could issue public performance permits and that political and religious matters could not be discussed in plays. In 1572, she also established that to sponsor a theatre troupe, the sponsoring gentleman had to be at least of the rank of a baron.

With the new restrictions and regulations, theatre companies could also opt not to have a noble sponsor, but they then needed to get a permit from a local Justice of Peace to perform in that town. This new system indicated that a license was to be obtained in every town the troupe wanted to perform, and that traveling from one town to another did not represent an act of vagabondage any longer.

Needless to say, to obtain a license, troupes had to pay a fee, which made this whole ordeal quite profitable for the crown. Just to provide an idea, it has been estimated that between 1572 and roughly 1642, there were around one hundred theatre troupes on tour through England.

In 1574, a Royal Patent was instituted and it provided an even stronger royal control over the troupes. It gave the power to license a company’s plays directly to the Master of the Revels, who was in charge of the queen’s entertainment, and who served directly under the Lord Chamberlain (the manager of all the needs of the royal household).

From 1598 onward, the Master of the Revels was also in charge of licensing playhouses: the theatrical spaces.

As the population and the need for entertainment grew exponentially all over England, the situation became particularly challenging in London, with theatre troupes fighting over spaces and plays. The queen’s response to this was to give the monopoly of performing in London and its suburbs to only two professional theatre companies: the Admiral’s Men and the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. For the record, said monopoly worked to a certain extent but didn’t last past the Tudor monarchs. With the advent of the Stuart monarchs, the royal patent was retained, but licensing through the Master of the Revels also became an option.

Let’s take a look at professional theatre companies working at the time.

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men was arguably the most important theatre troupe operating in London. It was founded in 1594 and included the most famous and revered actors and theatre artists of the time, including Richard Burbage (one of Shakespeare’s leading actors, who originated the roles of Hamlet, Richard III, Lear and Othello), Will Kempe (who played comedic roles), and last but not least, Shakespeare himself. From 1599 onward, the company performed almost exclusively in the newly built Globe Theatre in the summer, an outdoor public playhouse just outside the city close to the River Thames, and in the Blackfriars Theatre in the winter, an indoor private theatre within the city limits. When James I became king in 1603, the company was renamed the King’s Men.

The Admiral’s Men first performed at the Rose Theatre, an outdoor public playhouse not far from the Globe Theatre, and then moved to The Fortune Theatre. The most prominent actor in the company was Edward Alleyn.

Professional theatre companies were organized as a cooperative, which means that in order to be part of the company, the actors had to become shareholders. As shareholders, they would cover the leading positions, including the main roles in the play and in the management, they would get a share of the profits, but they would also be financially responsible for the cost of the productions and of the maintenance of the space.

London-based companies had up to twelve shareholders, while touring companies tended to be smaller, with about half a dozen of them.

Companies sometimes had a resident playwright, as in the case of Shakespeare for the King’s Men, and if that was the case, it wasn’t unusual for plays to be written keeping in mind the specific actors available within the troupe. Otherwise, troupes would hire a playwright and commission new work. While copyright laws didn’t exist at the time, hired playwrights would receive a flat fee, the amount of which depended on the popularity of the playwright.

Good plays were a property of the troupe and could potentially be published if they obtained the patent for it. Yet, the most successful plays stayed unpublished so as not to allow access to them by other companies, which is why none of Shakespeare’s plays were published during his lifetime. Once the company owned the play, it still needed to be licensed by the Master of the Revels to be produced. One of the tasks of the Master of the Revels was to make sure that the play didn’t deal with destabilizing subject matters. Anything politically or morally troubling was cut, or censored.

Each company had a rule of conduct everyone should abide by that determined fines for actors if they, for example, arrived late at rehearsals, damaged a costume, were drunk on the job, and so on.

Aside from shareholders, there could be hirelings – actors hired to cover a specific, usually small, role in a production – and finally, apprentices – young aspiring actors who were assigned to a resident actor for training and who often played female roles, as women were not allowed to perform.

Both the King’s Men and The Admiral’s Men were adult companies, meaning all of the actors were adults, as opposed to what happened in boys’ companies, which were also popular.

These were professional troupes which had to obtain the same kind of license as the adult companies to perform, and which had a similar shareholding structure, except that the actors – the boys- could only reach the status of apprentice. Most of the young actors came from choir schools and were then funneled into acting in plays to improve their communication skills. Boys’ companies were popular at court, and they also performed in smaller venues, such as the Inns and the first Blackfriars Theatre (as opposed to the second Blackfriars Theatre, where the King’s Men would perform). The most famous boys’ troupes were The Paul’s Boys and The Blackfriars Boys. Boys’ companies would get their plays from notable playwrights such as Ben Johnson and Thomas Middleton.

A theatrical season could last a bit short of fifty weeks, with up to forty being produced by the same company, hence the ongoing need for new plays. A successful play could be revived and rewritten several times, but the amount of new work was always higher. That meant that many playwrights dug into pre-existing material such as chronicles, classical myths, and novellas as the spine of their works.

Successful theatre companies would be very busy and would always have a production running, which meant that they had a repertoire of plays and assigned roles that could facilitate a quick turnaround. Rehearsals for a new play couldn’t last long and could not disrupt the performance schedule of the company. Because of this, it was common practice to have a prompter close to the stage, to feed the actors their lines should they need it.

The greatest obstacle to the continuity of theatrical activities was … the plague, which caused theatres to suspend all activities for months at a time, like in 1609.

Most of the time, actors were only given the sides containing their lines and their cues, while the entire script was kept somewhere safe. That prevented, to some extent, the theft of scripts. Actors would have access to the overall plot and timeline of the play – as they would be available backstage.

When it comes to the acting style of the time, scholars have little to go on, and therefore, nothing definitive can be said.

A famous scene in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Act 3, Scene 2, see BOX) could shed some light on the matter. While discussing with the touring acting troupe that had just arrived at Elsinore, Hamlet makes specific requests about the way the actors should deliver their lines and their performance. That text suggests a realistic style of acting, with a final emphasis on respecting the text as provided by the playwright. Fun fact: many think that the line: “and let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them” is a direct reference to one of the King’s Men company members, Will Kempe, who played comedic roles and might have taken some liberties on his provided text, displeasing Shakespeare.

While Hamlet’s speech on acting is truly wonderful and can indeed be applied to modern acting, it seems unlikely that realism—at least in the way we conceive it today— was really what Elizabethan acting was all about. First of all, women were not allowed on stage, and all female roles were played either by boys, sometimes the apprentice, or by company members if roles required older actors. There was likely a convention about stylized gestures, postures, tone, and pitch of the voice that differentiated characters, both in terms of gender and of status. These elements alone defeat any attempt at realism.

Secondly, most of the focus was on the language as the primary vehicle of storytelling. There was little or no scenic design as a visual support for the play (more on this later). Details about locations and environment were delivered through exposition, that is to say, within the dialogue between the characters. What the audience would see is something very close to a bare stage, with actors entering and exiting at the beginning and at the end of each scene.

Lastly, most companies needed to assign several roles to the same actors due to the characters outnumbering the actors they had available.

Hamlet’s Speech on Acting. Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2)

HAMLET

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced

it to you, trippingly on the tongue. But if you mouth it

as many of your players do, I had as lief the town-crier

had spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much – your hand, thus – but use all gently. For, in the very torrent, tempest and, as I may say, the whirlwind of

passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that

may give it smoothness. O, it offends me to the soul to

see a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to

tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings,

who for the most part are capable of nothing but

inexplicable dumb-shows and noise. I could have such

a fellow whipped for o’erdoing Termagant – it out-

Herods Herod. Pray you avoid it.

PLAYER

I warrant your honor.

HAMLET

Be not too tame neither, but let your own

discretion be your tutor. Suit the action to the word, the

word to the action, with this special observance – that

you o’erstep not the modesty of nature. For anything so

overdone is from the purpose of playing whose end,

both at the first and now, was and is to hold as ’twere

the mirror up to Nature, to show Virtue her own

feature, Scorn her own image, and the very age and

body of the time, his form and pressure. Now this

overdone, or come tardy off, though it make the

unskilful laugh, cannot but make the judicious grieve,

the censure of the which one must in your allowance

o’erweigh a whole theatre of others. O, there be players

that I have seen play and heard others praise – and that

highly – not to speak it profanely, that neither having

the accent of Christians nor the gait of Christian,

pagan nor no man have so strutted and bellowed that I

have thought some of Nature’s journeymen had made

men, and not made them well, they imitated humanity

so abhominably.

PLAYER

I hope we have reformed that indifferently with us, sir.

HAMLET

O, reform it altogether – and let those that play

your clowns speak no more than is set down for them.

For there be of them that will themselves laugh to set

on some quantity of barren spectators to laugh too,

though in the meantime some necessary question of the

play be then to be considered. That’s villainous and

shows a most pitiful ambition in the fool that uses it.

Go, make you ready.

Because of the lack of scenery, the spectacle relied on costumes. Theatre companies cherished their “stock” of costumes dearly. Most of their items would come from donations from noble families and the occasional purchase, also made possible thanks to the allowance they would receive or from the revenue coming from the box office. Actors were asked to treat their costumes with care, and they were not allowed to wear them when not on stage. Failing to comply with this rule would result in a hefty fine.

All costumes reflected the fashion and the style of the time, which means that there was no attempt at period style costuming if the play required it: Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, for example, would have actors wear Elizabethan costumes instead of period-appropriate Roman-style garments. Needless to say, this element also works against a realistic approach to production.

When it comes to style, subject, structure, and characters, Elizabethan theatre varied significantly. The Aristotelian unities (unity of time, space, and action as discussed in previous chapters) were not respected, as all plays presented several locations.

Comedies had more complicated plots, seldom included at least one character that functioned as the “fool” or as a “clown”, tended to be shorter than tragedies, and featured characters who were not necessarily of noble birth (but could be). The subject matter could vary from pastorals, household themes, complicated love stories with, of course, a happy ending.

Both prose and verse were utilized in comedies, and music was frequently added as well.

Tragedies presented a serious subject matter and didn’t have the ultimate “happy ending,” while they did deliver some sort of moral in order to make sense of the character’s demise. Tragedies also used both verse and prose, depending on which character was delivering the lines. While this is not a universal truth, noble characters would normally speak in verse (in particular when talking to each other), while lower-class characters would speak in prose. Elizabethan tragedies featured characters of noble birth as their leads. In terms of structure, tragedies tended to focus more on the main action, with fewer subplots. Shakespeare often introduced some sort of comedic relief element in his tragedies to allow the audience to “catch a breath” now and then.

The one common element for all plays was their length: they were much longer than what we are used to today. Most Elizabethan plays produced today (including all of Shakespeare’s plays) are heavily edited and cut to keep the production under two and a half hours.

In their time, performances would go way beyond the three-hour mark. Playwrights had to accommodate lots of repetitions, mostly because audiences were not as “disciplined” as we expect them to be today. Performances in public playhouses in particular could see the actors being seriously challenged by the audience, as people used to go to the theatre not only to experience the play, but also to meet with friends, discuss whatever matters they needed to, and…to drink! You can imagine how that might have contributed to discussions getting more heated and devolving into fights. In short, actors had to repeat the text in order for the rowdy audience members to catch up with the story.

The situation was overall better in private playhouses, as they were smaller and more expensive to attend.

The Iambic Pentameter or Blank Verse

The Iambic Pentameter (or Blank Verse) is a verse that has a specific syllabic rhythm (unstressed, stressed) and structure. “Iamb” stands for a metrical foot of two syllables, while “penta” means five in Greek, which implies that a line of verse in Iambic Pentameter uses five feet of two syllables, for a total of ten syllables.

The rhythm has been exemplified as follows:

“da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM”

Each “da DUM” is a foot of two syllables, the first one (da) unstressed, the second one (DUM) stressed.

Example (unstressed syllables are lower case, stressed syllables are upper case):

“shall I compare thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”

(William Shakespeare, Sonnet 18)

Theatrical spaces

We have briefly mentioned a few theatrical spaces in the previous sections. Now we are going to explore them in greater detail.

University student-led productions would premiere in the main halls in Cambridge or Oxford, where removable theatrical structures were positioned. If they were successful, they would move to London and perform in the Inns of Court, in what would now be the financial district. The Inns of Court were the following: Gray’s Inn, Lincoln’s Inn, the Inner Temple, and the Middle Temple. These spaces belonged to the lawyer’s associations and consisted of several buildings such as libraries, lounge areas, accommodations for students continuing their education in the field (in law, but also the arts), and a church. Access to these facilities was not for everyone, as you can imagine. Performances were public, but with space being limited, tickets would be expensive. The type of performances was also a discriminating factor: both the subject matter and the style tended to be elevated and comprehensible to a more educated audience.

There were also other Inns throughout London that appealed to less academic and learned companies. Some of them included The Cross Keys and The Bell, and The Bull. In these cases, the yard area was adapted into a performance space with the addition of a removable wooden structure functioning as the stage, while the audience would either stand in the yard or sit in the surrounding galleries.

Playhouses were also popular. These were buildings specifically conceived and built for theatrical activities, and they were very popular in London, specifically.

There were two types of playhouses: outdoor public ones and private indoor ones.

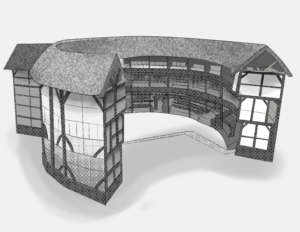

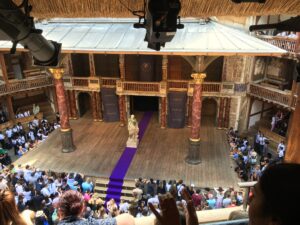

The outdoor public playhouse is the most iconic and the one that is commonly associated with Shakespeare. It saw several developments during the following centuries, culminating with the 1997 reconstruction of The Globe Theatre in London, in a location supposedly not far from the original playhouse by the same name. Despite its popularity, the evolution of the architecture of the outdoor playhouse isn’t totally clear to scholars. There is some late 16th Century artwork by Johannes De Witt, depicting The Swan Theatre as well as the actual contracts for the construction of The Fortune Theatre and The Hope Theatre, dated 1600 and 1613. Yet, these documents aren’t exhaustive and only provide an idea of some aspects of the buildings rather than covering the general concept behind them.

What we can conclude about the buildings and how they functioned is the following:

All the outdoor public playhouses were made of wood, mud, and straw, which didn’t make for the safest and most durable buildings. Theatres often burned to the ground and had to be rebuilt several times.

Most of the buildings had a polygonal ground plan, enclosing an inner yard.

The stage was a 4-feet high raised platform that extended into the inner yard – thrust style- from one of the sides and out of the tiring house, the Elizabethan equivalent of the Greek skene. The Tiring house had several doors onto the stage to allow entrances and exits and provide the actors some backstage space where they could store properties and change costumes. Some scholars believe there might have been a smaller, removable, and adaptable structure to be placed on the stage, against the tiring house, to make “revelation moments” possible. While this theory would explain and solve several blocking needs in most Elizabethan plays, there is no hard evidence to support its existence.

The Tiring house had a second level, with windows open to the stage, which would help when levels were needed – think of the balcony scene in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

The stage and the Tiring house were roofed, and were referred to as the “heavens” because they were painted with images of the heavens.

As for the audience seating, there were several options. There were three tiers of seating around the perimeter of the building. The first tier was divided into boxes, also known as the Lords’ rooms, for the wealthiest patrons. The other two tiers represented the galleries, with wooden seating on the second level and standing places at the top level. Finally, the cheapest tickets in the house were for the yard itself, or the pit, where the groundlings, as they were called, would stand, trading a cheaper ticket price and greater proximity to the stage for being completely exposed to the weather, as the yard had no roof.

Public houses worked primarily in the summer because of the warmer temperatures and light conditions. Performances started at 2 pm and could last up to four hours.

Eating and drinking during performances was allowed! Popular concession items were nuts, fruits, oysters, wine, and beer.

Between 1567 and 1623, we know of thirteen public playhouses in the London area. All of them were actually outside the city limits, as public theatrical activities were not allowed in the city. They all varied in overall size, seating capability, and stage dimensions. At the peak of their popularity, it is believed that public playhouses could house 1000 to 3000 people.

Out of all the public playhouses, the most important ones are: The Red Lion, The Rose, The Theatre, The Globe, The Swan, The Fortune, The Boar’s Head, and The Curtain.

The Theatre, built in 1576, was for a long time considered the model for all the others. It had been built by James Burbage. In 1599, its lease expired, and Burbage’s two sons, Cuthbert and Richard (also the famous actor in the King’s Men) dismantled it and used its wood to build The Globe Theatre.

Private indoor playhouses were located inside the city limits. It is believed that between 1575 and 1635, you could find eight private theatres in London, including the first Blackfriars (built in 1576) and the new (or second) Blackfriars (built in 1596).

These theatres were smaller than public houses, with a seating capacity set between 500 and 1000 people. Originally, they were exclusively used by Boy’s companies, but after 1608, adult companies took over most of them. These spaces made for a more intimate theatrical experience, being confined within one big room and a building.

While they were called “private”, they were indeed open to the public! Tickets were more expensive compared to public outdoor playhouses, due to the limited number of seats. Depending on the theatres, there were two or three orders of galleries, some boxes, and pit seats. There was no standing area.

The stage was on a raised platform, much like in public playhouses. Usually, there was no seating on the side of the stage, making it less of a thrust. Yet, the lack of a proscenium arch didn’t make for a proscenium arrangement either. The actors had access to a “tiring house” upstage as well, allowing entrances and exits, off-stage costume changes, “revelation moments” and prop storage.

The most important private theatre is by far the second Blackfriars, built by James Burbage and utilized by the Blackfriars boys as their home venue until 1608, when King James I passed it down to the King’s Men.

Playwrights

Shakespeare (1564-1616)

The time has come to discuss the “elephant in the room”: William Shakespeare, certainly the greatest English playwright, arguably the greatest in Western Theatre, and a household name all over the world. For the economy of this book, it is impossible to provide an accurate recollection of all the reasons why he is so popular and important, and deciding what to write about him here is definitely a challenge.

Shakespeare was born into a relatively wealthy family in Stratford-upon-Avon, a small town ninety miles north-west of London. He grew up there and attended the local Grammar School, where he was exposed to the classics and most of Plautus’ comedies, written in Latin. He was likely fluent in Latin and might have known some French. We don’t know exactly when he moved to London, but it is assumed that he pursued acting there for a while prior to his turn toward playwriting and producing.

He became a shareholder of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men) in 1594 and remained so until his retirement in 1613. After him, John Fletcher (1579-1625) became the resident playwright for the King’s Men.

Most of his work fell under two different monarchs: Queen Elizabeth I and King James I.

He was a popular playwright in his own time, although not nearly as much as he is now.

At the time, he was just as famous as Christopher Marlowe, Ben Johnson, or Thomas Middleton.

A lot about Shakespeare’s life is still unclear. Some scholars even question his actual existence…or the authorship of “his” works!

The evidence and the documentation that survived don’t allow for a precise recollection of his biography or his works.

In his over twenty year long career he surely wrote more plays than the surviving thirty eight, but because he never published any of them in his lifetime we are only able to enjoy the ones that were put together by his company after his death and that were published in the first anthology of his works: The First Folio (1623).

Some scholars have argued that he might not have been the sole author of some of his plays, and there is indeed a strong possibility, based on the differences in writing style that can be found in sections of certain plays, that he worked together with Thomas Middleton (possibly on Macbeth and Timon of Athens), George Wilkings (possibly on Pericles), and John Fletcher (possibly on Two Noble Kinsmen and Cardenio). There is also the belief that he might have worked with Christopher Marlowe on the Henry VI plays. Yet again, all this is speculation based on the analysis of the text rather than on facts coming from hard evidence.

Regardless, Shakespeare wrote a lot and fast because he needed to provide his company with new plays almost constantly. And while this is not unusual for the time, it has to be said that all of his work, except for The Tempest, is not original in subject matter. He heavily relied on previous sources, such as historical chronicles, novellas, and Latin literature.

Some of the features that make Shakespeare stand out are: the attention to character, the compelling storytelling, and the brilliant use of language.

Differently from previous (or many of his contemporary) playwrights, Shakespeare’s characters show an innate humanity that has allowed them to become at the same time archetypical and universal. Romeo and Juliet are the epitome of the “lovers”, but at the same time, the depth of their individual growth throughout the play gives them qualities that are unique to them. Similarly, Hamlet embodies the “coming of age” that is so typical of teenagers, while also showing a spirit of nobility and commitment to a cause well beyond his age. These examples could go on and on. Shakespeare focuses on the characters’ emotional – and physical— journey and then builds the plot around them, in particular when it comes to tragedies, so that the audience can empathize with them and follow the play more easily. Another device he uses is to make the main conflict and themes of the plays very relatable: jealousy, betrayal, injustice, ill-starred love, dysfunctional family dynamics, and honor.

Lear’s unfair behavior towards his one faithful daughter versus his doting over his other two deceitful daughters was, unfortunately, a common family dynamic back then, as well as today. Audience empathized with that because they recognized and understood the situation, as they might have lived through it themselves or knew someone who had.

Shakespeare wrote thirty-eight plays, and they can be grouped as follows:

History plays:

Henry IV part 1 and Henry IV part 2

Henry V

Henry VI part 1, Henry VI part 2, and Henry VI part 3

Henry VIII

King John

Richard II

Richard III

Tragedies:

Antony and Cleopatra

Coriolanus

Hamlet

Julius Caesar

King Lear

Macbeth

Othello

Romeo and Juliet

Timon of Athens

Titus Andronicus

Cymbeline

Troilus and Cressida

Comedies:

All’s Well That Ends Well

Midsummer Night’s Dream

As You Like It

Much Ado About Nothing

Love’s Labour’s Lost

Two Gentlemen of Verona

Twelfth Night

Winter’s Tale

Taming of the Shrew

The Merry Wives of Windsor

The Tempest

The Comedy of Errors

The Merchant of Venice

Measure for Measure

Pericles (this play was not included in the First Folio, as it had been previously published as a pamphlet. It was later included in the third edition of the Folio).

The Two Noble Kinsmen (this play, as well, was not included in the First Folio. It was first published in 1634).

There could be more nuances to these groups, as some plays feature a combination of elements that makes their sharp identification with just one genre problematic.

For example, Measure for Measure deals with the dishonesty and corruption of a politician who blackmails a young novice. If she doesn’t sleep with him, he will have her brother executed on moral grounds. The play is still considered a comedy because of the happy ending where the legitimate and lawful order is restored and “true love” is rewarded.

Another example is The Merchant of Venice, where one of the main characters, Shylock, a Jew, is depicted in a prejudiced way while at the same time is given one of the most touching monologues about equal rights.

Measure for Measure and The Merchant of Venice have also been labeled “problem plays”, along with All’s Well That Ends Well, Winter’s Tale, Troilus and Cressida, and Two Gentlemen of Verona.

“Problem plays” shift in tone and subject matter, alternating very comedic scenes with darker ones while using ambiguous language.

Shakespeare Trivia and Fun Facts

Shakespeare’s plays have been translated into over one hundred languages.

They have been produced all over the world (and still are).

They have been adapted in movies, modern plays, musicals, comic books, video games, you name it.

It is safe to say that there are likely hundreds of Shakespeare’s plays being produced at any given time all over the world.

In the U.S.A. alone, there are several prestigious Shakespeare Festivals, reproductions of the Globe Theatre – one of Shakespeare’s preferred venues in London – universities and conservatories exclusively focusing on Shakespeare training.

Any famous actor you might think of, from Al Pacino to Benedict Cumberbatch, has performed in a Shakespeare production, if not several.

Any amateur or professional actor you might come across has likely been involved in a Shakespeare production.

Every actor, in general, is likely to have one of Shakespeare’s characters as their “dream role”.

Most children are exposed to at least one of his plays when they are in high school.

Shakespeare invented about 1700 new words that are still in use today. Examples include: gossip (The Comedy of Errors), shooting star (Richard II), alligator (Romeo and Juliet), eyeball (Tempest), addiction (Henry V), and outbreak (Hamlet).

Hamlet married Anne Hathaway, who was ten years older than him, and had three children: Suzanna and the twins Hamnet and Judith. Hamnet died a young boy, and it is believed that the character of Hamlet was named after him.

It is believed that Shakespeare was cast as the Ghost of Hamlet’s father in the original production of Hamlet.

In 2020, a copy of the First Folio, the first anthology of his plays published after his death, sold at auction for a little under ten million dollars, making it one of the most expensive books of all time.

He wrote some of the most famous speeches of all time, including “To Be or Not To Be” (Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 1), “All The World’s A Stage” (As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 7), “She Should Have Died Hereafter” (Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5), “Galop apace, you fiery-footed steeds” (Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, Scene 2), “But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?” (Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 2).

Within his plays, one can find the most incredibly effective insults of all time. Examples include: “I do desire we may be better strangers.” (As You Like It, Act 3, Scene 2), “Tis such fools as you that makes the world full of ill-favored children (As You Like It, Act 3, Scene 5), “More of your conversation would infect my brain” (Coriolanus, Act 2, Scene 1), “You have a February nose, so full of frost, of storm and cloudiness” (Much Ado About Nothing, Act 5 Scene 4), “Thou hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows” (Troilus and Cressida, Act 2, Scene 1)

He likely wrote more, but what has survived are 38 plays and 154 sonnets.

The only play with original subject matter is his last one, The Tempest, which is also considered his farewell to the theatre.

Examples of movies, plays, TV series, novels, and musicals inspired by or adapted from Shakespeare (in no particular order):

Star Wars Shakespeare, by Ian Doescher. The author rewrote the Star Wars saga in iambic pentameter. He also applied the same treatment to other famous movies and literature. Examples include Much Ado About Mean Girls, William Shakespeare’s Dracula, and William Shakespeare’s Get Thee… Back To The Future.

West Side Story – by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim. This famous and multi-awarded musical is an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet.

British actor and director Kenneth Branagh, aside from acting in a variety of Shakespeare roles and plays, has directed several movie adaptations of the Bard’s work, including: Hamlet (he played Hamlet), Henry V (he played Henry V), Much Ado About Nothing (he played Benedick), As You Like It (only directed).

Slings and Arrows – A Canadian television series about a theatre company working on a Shakespeare play.

It has been argued that The Lion King is a loose adaptation of Hamlet, as it is a “coming of age” story.

Most of Shakespeare’s plays have been adapted, some even several times, into screenplays. The list would be too long to include here….. A brief research will give you the entire list.

10 Things I Hate About You, a contemporary movie adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew.

Prospero’s Books, by Peter Greenaway, is a British avant-garde movie adaptation of The Tempest.

Kiss Me, Kate by Cole Porter is also an adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, by Tom Stoppard. The plot revolves around the two Hamlets’ “friends”. Originally a play, it was also turned into a movie.

Ran, by Akira Kurosawa, is a movie adaptation of King Lear.

Something Rotten! Book by John O’Farrell and Karey Kirkpatrick, and music and lyrics by Karey and Wayne Kirkpatrick. This musical comedy tells the story of Shakespeare’s theatre company. In the original 2015 Broadway production, Christian Borle played Shakespeare, winning a Tony Award for his performance.

The Boys from Syracuse, music by Richard Rodgers and lyrics by Lorenz Hart, is based on The Comedy of Errors.

And Juliet, featuring music of Swedish pop songwriter Max Martin and book by David West Read, is a re-telling of Romeo and Juliet, with a very different ending.

Kill Shakespeare, a comic book limited series centered on several of Shakespeare’s characters.

Shakespeare’s plays have also been rendered into graphic novels and manga.

Fat Ham, a play by James Ijames, is a modern adaptation of Hamlet. The play was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2022.

American playwright Lauren Gunderson has written several plays based on or inspired by Shakespeare’s work and life. Examples include A Room in the Castle, a re-telling of Hamlet from the perspective of Gertrude, Ofelia, and Ofelia’s handmaid, The Book of Will, about the creation of the First Folio, and Exit Pursued by Bear, which uses Shakespeare’s words and quotes within a completely original framework.

Thomas Middleton (1580-1627)

Middleton wrote and co-wrote several comedies and tragedies, although his style and dramatic structure were not the most compelling. His comedies focused on the life of wealthy Londoners and are characterized by a witty use of language. Comedies include: Michaelmas Term and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Middleton’s tragedies focused on the demise of the main character due to corruption and had really dark tones. Examples include: The Changeling, A Game at Chess, and Women Beware Women.

Ben Johnson (1572-1637)

Johnson is probably the most famous playwright of the time, after Shakespeare.

He came from a lower-class family that could not afford to send him to school, so he fed his thirst for an education in the classics by studying on his own. He was particularly fascinated with the neoclassic principles, which he tried to incorporate in his works.

Later, he enrolled in the army, thus gaining a higher social status when he came back from the war.

He is best known for his comedies, the most famous ones being Volpone, The Alchemist, and Every Man in His Humour. His characters were built following the contemporary medical theory of the four bodily “humours”: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Doctors at the time believed that health was determined by the balance of these four humors. Johnson’s characters showed an excess in one of them, therefore being unbalanced.

Ben Johnson considered writing plays just as important as writing any other form of fiction or poetry, and he thought that plays should be elevated to the rank of literature. So, while most of his contemporaries didn’t bother to publish their plays, he published an anthology of his work in 1616 that he personally curated.

His later works included two tragedies, Sejanus and Catilina.

His elegant style made him particularly appreciated by the aristocracy, and he became King James I’s protégé. In 1615, the king bestowed on him the title of “poet laureate” and gave him a royal pension.

He led a tumultuous life, frequently engaging in heated debates with fellow playwrights. In the so-called “war of the theatres”: he wrote satirical comedies to make fun of his rivals. He was incarcerated twice, once for being involved in a production that was considered “offensive” and the second time, in 1598, for killing an actor in a duel.

John Webster (1580-1634)

Webster is remembered for his well-written tragedies and strong characters. His main characters had decisive traits, but were morally flawed, which inevitably led to their violent demise. He used very poetic language, which was much appreciated by the aristocracy.

Yet, his plays lack a strong main action, making it for a sometimes scattered plot.

His most famous works are The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil.

He is believed to have collaborated with several other playwrights, including Thomas Dekker, Thomas Middleton, and Thomas Heywood.

Other playwrights of the time who significantly contributed to this time period are John Fletcher and Francis Beaumont, both coming from a wealthy and learned background. They frequently worked together and are believed to have authored over fifty plays, most of which were tragicomedies, which became a very popular genre in the Caroline period. Tragicomedies associated serious themes akin to tragedies, with a more uplifting and happy ending. Many scholars find their style to be the origin of what will become the typical wit of the Restoration (after King Charles II restored the monarchy in 1660).

Finally, other playwrights of the time worth mentioning are Thomas Dekker, John Marston, and Tomas Haywood.

TAKEAWAYS

England’s Renaissance developed over the reign of three monarchs: Queen Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I.

Tragedies still featured main characters of noble birth, but did not follow the unity of space.

Comedies relied on more relatable subject matters and featured everyday characters.

The productions were not realistic in style, and neither was the acting.

Women were not allowed to act; men played all female roles.

Professional theatre companies needed to have the patronage of an aristocrat or of the monarch in order to perform.

Licenses to perform were appointed by public officials, and censorship was common.

There were two different types of theatre companies: boys’ troupes and adult’s troupes.

Universities (Oxford and Cambridge) played a significant role in the development and the growth of the popularity of theatre.

Theatre companies would perform in London and tour outside the town (and they needed a permit to perform in every town).

Companies would perform in Inns, Indoor Private Playhouses, and outdoor public playhouses.

Theatre companies were structured as cooperatives, with the main actors being shareholders.

Of course, Shakespeare. And then, everyone else other than Shakespeare.

Vocabulary

Humanism

Queen Elizabeth

King James I

King Charles I

House of Tudor

House of Stuart

University Wits

Inns

Gorboduc

Royal Patent

Master of the Revels

Lord Chamberlain’s Men/King’s Men

Admiral’s Men

Boys’ companies

The Globe Theatre

The second Blackfriars Theatre

Iambic Pentameter/Blank Verse

Tiring house

Heavens

Tragicomedies

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

Divide the students into groups of 4 – no big groups for this activity.

First, assign each group a famous speech from a Shakespeare play.

Examples: “All The World’s A Stage” (As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 7), “No matter where. Of comfort no man speak.” (Richard III, Act 3, Scene 2); “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears” (Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 2); “But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?” (Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 2); “Now is the winter of our discontent” (Richard III, Act 1, Scene 1); “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more” (Henry V, Act 3, Scene 1).

Give each group 10 minutes to read the speech.

Then, a representative of each group will read the speech out loud to the rest of the class. This is not an acting exercise! Just read the lines out loud.

Each group will have to say one thing they understood from each speech, just by hearing it.

Then, give each group another 10 minutes to go over the text and translate it into modern English. It would be best if the students didn’t have access to phones or computers at this stage.

When they’re done, each group should once again read the speech out loud, but this time in their modern English translation.

A discussion should follow about how much (or how little) they had understood of the speech before the translation. Then, they should focus on how the sound of the lines differs between Shakespeare’s text to the modern translation.

Is the sound contributing to creating an atmosphere? Did the rhythm of the Shakespeare original text also play a role in the overall listening experience?

Finally, with the help of Shakespeare’s lexicon (or a computer), finalize the correct word-for-word translation of the speech.

A discussion should follow about the Elizabethan rhetoric that can be found in Shakespeare (metaphors, similes, alliteration, antithesis, etc.).

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 1485 | House of Tudor Begins | Henry VII becomes king, founding the Tudor dynasty and bringing stability that enables the growth of Renaissance culture. |

| c. 1490s | Humanism Spreads to England | Inspired by the Italian Renaissance and Humanism emphasizes classical education, secular subjects, and individual potential, foundational to Renaissance drama. |

| 1558 | Elizabeth I Becomes Queen | Daughter of Henry VIII; her reign marks the height of the English Renaissance and strong royal patronage of the arts. |

| c. 1561 | Performance of Gorboduc | The first known English tragedy written in blank verse establishes the use of iambic pentameter in English drama. |

| c. 1570s | Performances at the Inns of Court | Law schools in London serve as venues for early modern drama and help develop playwriting talent. |

| 1576 | The Theatre Opens | Built by James Burbage, the first permanent public playhouse in England, launched the era of commercial theatre. |

| 1587 | The Rose Theatre Opens | Built by Philip Henslowe, became a major venue for plays by Christopher Marlowe and the Admiral’s Men. |

| c. 1580s–1590s | Rise of the University Wits | A group of educated playwrights—Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene, John Lyly, and Thomas Nashe—laid the foundations for English Renaissance drama. |

| 1592 | London Theatres Close Due to Plague | Outbreak of bubonic plague forces the closure of public theatres; Shakespeare begins writing narrative poetry. |

| 1594 | Lord Chamberlain’s Men and Admiral’s Men Form | Two dominant acting companies emerge; Shakespeare joins the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, while Edward Alleyn leads the Admiral’s Men. |

| 1596 | Blackfriars Theatre Leased | Indoor theatre leased by James Burbage; later becomes the home to the King’s Men. |

| 1599 | The Globe Theatre Opens | Built by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, became the most iconic playhouse of the English Renaissance. |