1 Chapter One – The Origin of Theatre and the Greeks

Chapter 1 – The Origin of Theatre and the Greeks

Introduction

If you are reading this book, you are probably a student with some – or more than some- interest in theatre. You might have already familiarized yourself with the stage, with the thrill of performing, or you might have contributed to a production in different capacities, as back stage crew or even designing, for example. Quite likely, you have an idea about what is being produced on Broadway, which famous actor is doing what, and have a go-to showtune you keep humming from time to time. You have heard of Shakespeare (hopefully), but you have mixed feelings about him. And now you have to learn about the history of theatre. You probably have mixed feelings about this as well.

Why is it important to study theatre history?

While there is no simple answer to this question, we can start by saying that learning history is important in every field. It allows us to understand the evolution of a specific topic, how we got to where we are now, what was successful (or not), and what consequences were triggered by something or someone. In other words, we learn from the past and we can apply that knowledge to what we do today and moving forward.

In theatre, specifically, it is safe to say that nothing we see nowadays is truly original. Even the most contemporary play or musical relies on elements that are part of the culture of the field. As much as it sounds cliché and might make you arch your eyebrows, it is quite likely that most of what we see on stage, to some extent, goes back to Shakespeare, the Greeks, or Brecht.

Theatre history teaches us why theatre is important to begin with, how it originated, and developed. It also helps us better understand the evolution of society itself, since it is a reflection and a commentary of it, and is oftentimes a direct response to it. For example, by studying Brecht, we learn not only about a specific theatrical style but also about the reason why that style was introduced. And that reason relies on the socio-political environment contemporary to Brecht. As society evolves, theatre evolves with it, and while that makes some texts feel “dated” or somewhat “obscure” at first, it all contributes to a vocabulary that is constantly morphing into a new language. In a way, theatre history shows the human side of history by presenting us with how human beings individually respond to global events, facts, and daily circumstances. It makes history personal, subjective, and easier to comprehend, since it is easier to relate to a scene that imitates reality and whose characters are like us. Aristotle mentioned in his Ars Poetica that theatre originated because humans tend to imitate and represent life, because they want to see what they are living through, either for educational purposes or for pure enjoyment. We will see how Aristotle elaborates on this later in this textbook.

Many of us live “in the moment”; we are so overstimulated and overwhelmed by what is going on around us and being thrown at us in so many different ways that it feels we don’t have the time or the need to just stop, take a breath, and evaluate the circumstances somewhat objectively. The pace at which society moves is so fast that our collective memory has a hard time keeping up, much like the film of an old-fashioned SLR camera — the thing that leaves an imprint is the very last thing to hit it.

That is why dedicating some time to intentionally study the past becomes imperative.

You were not born yesterday, and you are who you are because of the life you have lived and the circumstances you have experienced up until now. If this is true for you, it is true for all things that have a past, theatre included.

With so many different platforms available to us, live theatre becomes just one of the options available for performance fruition. Starting with the radio in the late 1800s, the big and small screens have later become a staple in our lives and in our daily consumption of entertainment, storytelling, and educational material.

Although it might sound inconceivable to many, there was a time when live performances, in theatres or specifically dedicated spaces, were the only option. And to this day, against all odds, audiences still go to the theatre to see live performances because the experience of live theatre is unique and cannot be compared to anything else. Theatre has survived and thrived since the dawn of time; it finds its way into our lives and our society because it speaks our language and evolves with it. This is exemplified by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which caused theatres all across the world to shut down for over a year. Many feared that that was it, and that the theatre business would never recover. And yet, here we are, with some of the most exciting and thought-provoking theatrical pieces being conceived and produced worldwide. Audiences all over the world are lining up to be “in the room where it happens.”

The Origin of Theatre.

Long ago, theatrical storytelling originated in ritualistic practices, both religious and secular.

The congregation would perform to please the Gods, to pay tribute to them, or they would do it for the spirits of Nature, to propitiate better conditions for their agricultural needs (a healthy harvest, rains). These performances would include dancing – or some form of choreographed movement- singing and chanting, and at times, even elaborate costumes and masks. Depending on the culture, participation in these rituals could include everyone or just a few select individuals. There is, unfortunately, very little material that has survived about these forms of theatre, as most of their traditions were passed down orally.

Yet, there are exceptions, where some cultures have documented events through art.

The cultures that we know used theatrical storytelling are the Egyptians, the Mesopotamians, the Greeks, and several Asian cultures, including those in China and India.

Egypt

In Egypt, almost every aspect of daily life – and death- was tied to a god, and paying tribute to the Gods was of the utmost importance. Life heavily depended on agriculture and the Nile River, whose floods brought much-needed nutrients to the sandy terrain, and that functioned as the main outlet for transportation.

One of the most famous Egyptian rituals followed burials, with the deceased being accompanied on their last voyage into the underworld by a specific boat that would grant them safe passage. The very detailed ritual is recorded on The Book of the Dead, written in hieroglyphs on papyrus and left beside the deceased in their final resting place.

Depending on their wealth, the dead would be buried in an underground chamber along with objects they would use in the afterlife, as well as a miniature of the boat itself. Clearly, Pharaohs would receive the most luxurious treatment, and the images of the Pyramids stand as a testament to the Egyptians’ construction abilities and resilience.

Osiris was the god of the afterlife as well as the god of fertility and agriculture. Most rituals were dedicated to him and his sister-wife, Isis, the goddess of motherhood, fertility, healing, and death. One of the most famous rituals was held in Abydos, and it told the mythical story of Osiris, who ruled Egypt and married his sister, Isis. Osiris’ brother killed him out of jealousy and scattered his dismembered body throughout the kingdom. Yet, Isis collected all the pieces and, with the help of a god, was able to bring his spirit back to life. Because he couldn’t live on earth as a spirit, his body was buried in Abydos, and he became a god in the underworld. Every year, from 2500 to 550 B.C., thousands of Egyptians would visit Abydos to attend the ritual of the reenactment of this story.

We know that Egyptian rituals made use of music, as archaeological remains of instruments have been found, along with images of musicians included in frescos. Dancing seemed to be part of it as well.

Historians also believe the Egyptians enjoyed performing arts as a form of entertainment, mostly for the more educated and the Pharaoh’s inner circle. Clues about this rest in the architectural remains of several palaces, where the space seems to suggest a potential division between performers and audience members.

Minoan Civilization

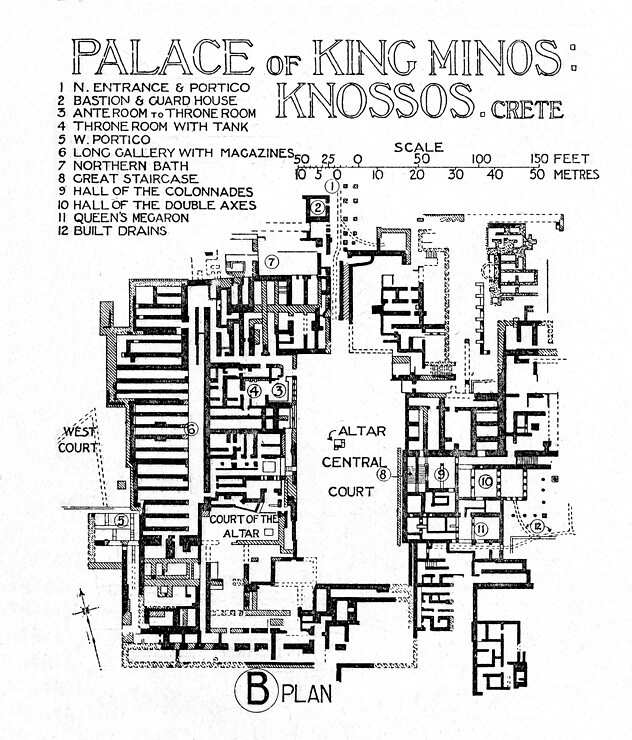

A similar situation can be found in Crete, where the Minoan society thrived between 2900 and 1400 B.C. They are considered one of the first advanced civilizations in Europe and beyond. The Minoans formed a very close-knit community, with a few independent settlements on the island. They were peaceful and didn’t engage in wars, so they instead dedicated their time to the arts. The archaeological remains of their citadels, or castles, show a great mastery of building techniques and advanced uses of engineering. For example, they had a system for collecting the water as well as a system to dispose of their waste. There won’t be anything as advanced as this until the Romans, much later.

Their palatial “castles” featured housing for most of the population of the settlements and included spaces that were specifically conceived and dedicated to performance. Remains of them can still be seen today in Knossos and Malia. Moreover, the palaces were very richly decorated with frescoes, many of which detail dances, musical performances, and other forms of entertainment, including sporting activities.

The Minoan civilization disappeared abruptly. Historians are still researching to conclude why that happened. Many believe that it was one of the consequences of the disastrous eruption of the volcano on Thera Island, the modern Santorini, around 1600 B.C.

The eruption made most of the island of Thera sink into the ocean, and the width of the caldera can still be seen today when visiting Santorini. The catastrophic event likely triggered a tsunami, destroying and gravely damaging several other islands, including Crete. Some believe that the floods on the Nile, mentioned in the Bible, were also a consequence of the Thera volcanic eruption.

Regardless, the Minoan civilization lost most of its power and withered away. What is left of it are the archaeological remains of the citadels/castles, scattered on the island of Crete. The Palace of Knossos is probably the most majestic site, and it has been heavily restored by Sir Arthur Evans at the beginning of the 20th Century. While his goal was to recreate the beauty of the site, he reconstructed several parts of the settlement with modern materials, stirring a great deal of controversy.

Unfortunately, while the Egyptians’ ancient hieroglyphs language has been codified and translated, the Minoans’ writing system of hieroglyphs, known as Linear A, has yet to be deciphered, so it hasn’t been possible to associate scripts with their performance practices just yet.

Asia has been a cradle for the arts in all of their forms, and theatre is no exception.

India

One of the richest Asian cultures when it comes to theatre is India. There is evidence of theatrical activities dating back to 1200 B.C. with the Rigveda, the oldest Vedic Sanskrit text. The text is divided into several books, each one focusing on a different topic, including cosmology, the gods, and more philosophical aspects of life. Its representation provided a form of theatrical storytelling that consisted of dancing and chanting along with dialogue.

Classic Sanskrit literature produced several theatrical pieces throughout the centuries. It is also a culture that has recorded the names of some playwrights, which is new for this time in history and won’t happen again until the Greeks. For example, we know of playwright and Buddhist philosopher Asvaghosa, who authored Buddhacarita, which is the first known Sanskrit drama. Generally, for Indian theatre, it is important to mention that while it had a strong religious and ritualistic element, it also provided an insight into characters and traditions belonging to worldly matters and was conceived as a form of entertainment as well. Scripts also included comedies, adaptations of fables, adaptations of religious Indu and Buddhist texts, and romantic storytelling.

Sanskrit drama flourished throughout several centuries and has influenced the evolution of theatre styles and genres, even outside of Asia and in more modern settings.

Another famous Sanskrit playwright is Kalidasa, who was active in the 4th Century A.D.. He has written several plays, some with a romantic nature and some adapted from the Mahabharata. One of his works has influenced Goethe’s Faust. Another known playwright is the emperor Harsha (600-648 A.D.), who is mostly famous for his comedy Ratnavali.

Latin America

Latin America also featured early forms of theatrical activities tied to the religious rituals of the indigenous people, and a lot of that tradition is retained in contemporary theatrical practices.

It has to be noted that most of these performative events, while similar in structure and concept to the Egyptians and the Indians, took place later in time compared to the other civilizations we have discussed.

The Aztecs and the Maya were probably the most prolific. They had Festivals to celebrate and propitiate nature, honoring the gods of rain to ensure a good harvest season. They also had staged representations dedicated to the gods of war, to gain their favor.

It is worth mentioning the Aztecs’ ceremony of the Flowery War, which included very choreographed and complex fights and ended with a human sacrifice.

The most famous Mayan theatrical ceremony was called Rabinal Achi [Man of Rabinal]. It tells the story of a warrior who protects the kingdom of Rabilnal with the aid of a Jaguar and an Eagle. He is attacked by a villain from a nearby land, but in the end, he captures him and brings him to justice. Interestingly, the narrative also features secondary female characters, such as the warrior’s wife and daughter.

The ceremony heavily used masks, elaborate and vibrantly colored costumes, music, and dance.

TAKEAWAYS so far.

The first forms of theatre were recorded in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Most theatrical storytelling stemmed from rituals, usually of the religious kind.

Performances originally featured everyone, not specifically actors.

Performances included dancing, singing, or chanting, and at times, some form of dialogue.

Some forms of costuming and masks were common.

Research opportunities.

Sanskrit drama and the several adaptations of the Mahabharata.

Peter Brook’s The Mahabharata. This very stylized movie adaptation of a stage play of the Mahabharata, directed by the same Brook, can provide an insight into Hindu storytelling and theatricality.

The Greeks

It is safe to say that Western theatre originated in Greece, specifically in Athens, between the 6th and the 5th Centuries B.C.. The very word “theatre” comes from the Greek word “theatron”, which translates to “the viewing place”.

Thespis is also a household name today, as we have many Thespian Festivals around the country (U.S.A.), and we normally refer to actors as “thespians”; why? Because Thespis is the first actor whose name has survived, thanks to Aristotle, who mentions him as the first person who appeared on a stage impersonating a character other than himself. He is also known as the “Inventor of Tragedy” as he is credited as the person who modified the structure of the dithyrambs, a form of poetry close to a hymn, into a dramatic script. He was active in the 6th Century B.C.

In the first chapter of the Poetics (335 B.C.), Aristotle mentions that theatre originated because humans have an interest in imitating and reproducing reality, which is, at its core, what theatre is. Specifically, Aristotle used the term “mimesis,” which means imitation. All things considered, the attempt by Thespis at transforming a poem into a scene with dialogue does indeed make for a more realistic approach to life.

Theatre was part of the everyday life of the citizens of Athens, and it was strictly connected to the cult of the god Dionysus. Most theatrical representations were held during city festivals and rituals dedicated to the God. These festivals were organized and produced by the Athenian government and culminated in a competition among productions. The participating plays were only tragedies, as that was considered the most appropriate, elevating, and culturally relevant genre of theatre.

Yet, comedies and satyr plays were also popular, although they had less of a patronage from the city. We will investigate the reason shortly.

There were three theatre festivals: the Lenaia (end of January), the Rural Dionysia (end of December) and the City Dionysia (end of March/beginning of April), or Great Dionysia, and all of them were related to the cult of the Dionysus and originated in the 6th Century B.C..

The Lenaia and the Rural Dionysia were of a smaller scale. They lasted for fewer days and featured fewer productions than the City Dionysia.

The Rural Dionysia took place outside the city-state [polis] of Athens, in Attica, between December and January to celebrate the winter solstice. The Great Dionysia instead happened first in Eleutherae, Attica, about three months after the Rural Dionysia as part of the celebration of the spring solstice. Then, the Eleuthereans brought the statue of Dionysus to Athens, intending to move the festival there as well. Yet, the Athenians weren’t originally keen on doing that, except that legend has it that Dionysus punished them with a plague that hit the men’s genitalia. When the Athenians finally accepted the statue and committed to the cult of Dionysus and to producing the festival, the plague was lifted as the god’s will had been satisfied. Every year, there would be a procession of Athenian citizens carrying bronze and wood phalloi as a remembrance of the event.

Despite the initial reluctance, Athens soon fully embraced the festival and grew very fond of theatrical competitions. Athenian citizens attended the festival as part of a civic duty.

The festival lasted several days and was very structured. The rituals started with a procession featuring all the producers, or the sponsors, dressed in expensive and complex costumes. Animal sacrifices were part of the opening ceremony as well to pay tribute to the god. The first day was dedicated to poetry, with a competition of dithyrambs, a form of poetry similar to a hymn and accompanied by music. At the end of the competition, animals – mostly bulls and goats- were sacrificed to the god.

The second and third days were dedicated to the theatre, with the presentation of the playwrights and their plays on the second day and then with the performances from the third day onward. Each following day would feature three tragedies and one comedy, all written by the same playwright. The festival culminates in a ceremony awarding the best tragedy, the best comedy, and later on, the best actor.

The festival was “produced” by the city of Athens, with an elected official, called an archon, in charge of putting together and supervising the team of judges evaluating the plays, as well as selecting the plays within a year before the festival. Moreover, the archon selected a producer, the choregus, for each play that was selected. Differently from today, where the producer is in charge of all the expenses and costs of a production but rarely uses their own money, the Greek choregoi (plural for choregus) personally paid for everything. The commitment to the festival was so strong that all the producers heavily invested in the productions, as it was a great honor to win. The festival lasted for several days.

All genres, tragedies, comedies, and satyr plays had a space in the City Dionysia, although there were great differences in each of their roles.

Everything happened either in the Theatre of Dionysus, on the slope of the Acropolis of Athens, directly below the temple of Dionysus, or in the Odeon, which was also right below the Acropolis. It is important to understand that all performances were held in the open air and during the daytime. Attendance was always high, with people coming from all over Greece. Whichever war was happening – and there was always a war somewhere in the region- it would be stopped for the entire duration of the festival to allow for people to attend the performance. It has been estimated that at the peak of its popularity, the City Dionysia was attended by 17,000 people, as there is evidence that roughly that many people could have been seated in the Theatre of Dionysus. To put things into a modern perspective, this kind of attendance is comparable to the American Super Bowl – which usually draws anywhere between 60,000 and 70,000 supporters.

The first tragedy to be performed is believed to be one by Thespis, in 534 B.C., and he was rewarded with a goat. The very word “tragedy” comes from this, as tragos, in Greek, means “he-goat.”

Spotlight: What is a polis?

The word “polis” in Ancient Greek means city, but its meaning spans wider than what we consider a “city” today. During Classic times, the Greeks were organized in structured communities functioning as independent, self-sufficient, and organized states. A polis was a small state. Ancient Greece was not a unified country, like today, but rather a territory comprised of several communities organized in a polis, which, most of the time, were at war with each other. For example, the rivalry between the polis of Athens and Sparta generated the Peloponnesian War that lasted almost thirty years (431-404 B.C.).

Theatrical Genres

We briefly mentioned the dithyrambs being the first form of performance, and how they evolved into what we can consider the first tragedy under the hand of Thespis.

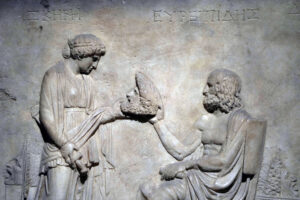

Tragedies soon became the most renowned genre and would develop greatly throughout the centuries ahead. This was through the work of some of the most important classic Greek playwrights, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.

Other important genres of performances included comedy and satyr plays.

Let’s break down each genre.

Tragedy

It is worth mentioning that scholars haven’t unanimously agreed on what is the origin of tragedy. There simply isn’t a lot of data that has survived, and most of what we know comes either from Aristotle’s Poetics or from later writings by the Roman historian Horace. We do know that Thespis introduced the division between the actor and the chorus, creating dialogue that allowed for the dramatic action to be more “realistic.” Further development of the structure of the tragedy came later with Aeschylus (523-456 B.C.), who introduced the second actor onstage, and finally with Sophocles (496-406 B.C.), who introduced the third actor and set the number of chorus members to fifteen. It is important to know that the playwrights were also directly involved in the production of their pieces, and often acted in them too.

The structure of the classic Greek tragedy is quite rigorous.

They start with a prologue providing exposition about events that happened before the play began. The prologue is followed by a parodos, marking the entrance of the chorus. At times, the parodos substitutes the prologue. Then we have a succession of episodes – three to six- where the story is developed. In between the episodes, we find stasima, choral songs. The play ends with the exodus. Tragedies were written in verse and only featured characters of noble birth. Most of the texts were sung, or chanted, and dance played a significant role in the productions.

Tragedies focused on myths that were very popular among the Greeks, and the playwrights had the freedom to interpret them according to what message they were trying to convey. That is why there are several “versions” of the same myth in the remaining Greek plays. An example of this is the myth of Helen of Troy, whose story is told very differently from common knowledge in Euripides’ play, Helen. In Euripides’ play, Helen didn’t run away with Paris to Troy, abandoning her husband Menelaus and thus causing the Trojan War. Instead, she was kidnapped by the gods and stranded on the shore of Egypt, where she was held captive, while a ghost of her was sent to Troy. The takeaway of Euripides’ Helen is therefore that the war at Troy had been triggered by a lie.

While the addition of dialogue and actors was intended to provide some realism to the production, we are still in a very stylized world. The three male actors played multiple roles, including female roles, because women were not allowed to act.

The use of masks allowed for a quick transition in characters. The masks being utilized represented the archetypical version of the characters, such as the messenger, the king, the queen, etc. They were likely made with a combination of straw and papier mâché, with a wide conic aperture by the mouth that allowed for a rudimentary amplification of the voice of the actors. The description of the masks, along with most of the terminology we are aware of regarding classic Greek theatre, comes from a much later source, the Onomasticon, a compendium written by historian Pollux around 170 A.D. He mentions the existence of twenty-five masks: three representing old men, eight representing young men, three representing servants, and eleven representing women.

Overall, tragedies tended to deliver a lot of exposition from the beginning to almost the middle of the play, thus reducing the main dramatic action almost to a minimum.

Most remaining tragedies abide by the Aristotelian unities of action, time, and location, meaning each play would focus on the development and resolution of one main issue. This would happen in chronological order over a day and would take place in one location.

The characters interacted with the chorus. Usually, the characters occupied a space opposite the chorus, as the chorus needed more space for the stylized movement/dance. When we speak of dance, it has to be noted that it was likely more a set of symbolic rhythmic movements associated with certain emotions, concepts, or characters, and widely known and recognizable by the audience. There wasn’t choreography as we know it today.

The function of the chorus is multifold. First, it provided some exposition for the audience to better understand the action; sometimes it functioned as “the voice of the people”, opposed to the character, providing insights on the framework of the ethical and social issue at stake in the tragedy. Then, it allowed for moments of change of pace in between the dialogue between the characters, thus making for a better experience for the audience. It also provided spectacle because of the dancing. Finally, at times, the chorus worked as the “ideal audience member”, directly reacting to what was going on between the characters and providing their point of view to the characters.

For the City Dionysia, each playwright was asked to write a trilogy – a set of three plays- and a satyr play. It is worth mentioning that only very few plays (31) have survived of the thousands that were produced between 534 and 400 B.C., and among the surviving ones, there is only one trilogy, Aeschylus’ Oresteia. This means that most Greek tragedies we read and produce today are the beginning, middle, or ending episode of a much wider storyline.

All the remaining plays were written by only three playwrights: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Clearly there must have been many, many more, but alas, only these three names have survived.

Classic Greek tragedies are still very popular today, with many of them being produced every year all over the world. Many of them have also been adapted in new plays by later playwrights throughout history and to this day.

Aeschylus (534-456 B.C.)

Aeschylus is remembered for adding a second character to the structure of the tragedies, although a third actor is present in the trial scene of his Eumenides. He was very active in the City Dionysia and won thirteen times. Aeschylus’ style and poetic structure are strongly rooted in history and myths, which he used to further his concepts. His plays focus more on the chorus than on the characters – it has been noted that in most of his plays, half of the lines are spoken by the chorus- and explore social concepts, such as justice, honor, and ethics. The characters engage in dialogue with the chorus to debate or confute the social issue, but most of the narrative is usually carried by the chorus.

There are records of over eighty plays authored by him, but the only surviving ones are:

The Persians – a history play about the Persian defeat after the battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. This is the oldest play that has survived.

Seven Against Thebes – the play revolves around the rivalry between the sons of Oedipus, and it was part of a trilogy called Oedipodea. The other two plays of the trilogy, namely Laius and Oedipus, along with the satyr play Sphinx, are lost.

The Suppliants – the protagonists of the plays are the Danaids, maids who fled their country in order to escape arranged marriages with the Egyptians. They seek refuge in the sanctuary city of Argos, where they ask for the help of the king. This play was likely the third play of the Danaid trilogy, which featured two other tragedies of which only the titles have survived, The Egyptians and The Daughters of Danaus. The satyr play concluding the suite is believed to be Amymone, also lost.

The Oresteia (Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides) – as mentioned before, this is the only trilogy that survives (aside from its satyr play). It develops the concept of justice, as it shows how personal revenge does not make it right, while only the rule of the land will restore true justice.

Prometheus Bound – the play tells the story of Prometheus, a Titan who defied Zeus by stealing fire and donating it to mankind. The authorship of this play is still debated, as some scholars believe its style suggests someone other than Aeschylus wrote it.

Sophocles (496-406 B.C.)

Sophocles lived a long and successful life. He is believed to have written over one hundred and twenty plays. He introduced the third actor and set the number of chorus members to fifteen in the tragedy, sanctioning the final form of the genre. He is believed to have won over twenty-four City Dionysia.

Sophocles’ plays revolve more around characters and character development than on the complexity of the plot, both elements that make him quite different from Aeschylus. Sophocles’ choruses are important, but they mostly support or antagonize the characters rather than functioning as characters themselves. This is also quite different from Aeschylus.

His plays also stood out for their elegance in the language and the overall structure. It is one of his plays, Oedipus the King, that Aristotle utilized as an example to describe “the perfect play.”

Only seven plays written by Sophocles have survived, and they are:

Oedipus the King – The preamble to the play is the myth of Oedipus, who flees his home to escape the Oracle of Delphi’s prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother. When he arrives in Thebes, he can eradicate a plague by solving the Sphinx riddle, and for that he is rewarded with the kingdom, and he marries the deceased king’s wife. Years later, a new plague hovers over the town, and to uplift it, the oracle tells him that he needs to find out who killed the previous king. In pursuit of the truth, he will discover that he had been adopted and that when he fled home, he set in motion his fate. He had killed a man at a crossroads, and that man turned out to be his real father and the previous king of Thebes. Hence, Oedipus had also married his mother, who bore him five children. Oedipus takes responsibility for his actions, blinds himself to show everyone that he had been blind all his life, and leaves Thebes in exile with his two daughters, Antigone and Ismene.

Ajax – The play follows a Trojan warrior, Ajax, who is enraged from being denied Achilles’ armor and is driven to madness by the goddess Athena.

Antigone – This play is one of Sophocles’ most famous plays. It explores the concepts of justice and ethics. Should the law of the land bypass the law of nature and ethics? Antigone is one of Oedipus’ daughters. After a long war, both her brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, are dead. Yet, they were on opposite sides. Creon, Antigone’s uncle and the ruler of the land, Polynices attempted to usurp, establishing that only Eteocles was entitled to burial rites, while Polynices’ body was to stay exposed to the elements to rot as an example for the people. Antigone questioned the righteousness of this decision and challenged it, knowing she would be facing death for her action. Yet, she claimed both brothers had to be buried to give them peace. When she is discovered, she faces death.

Oedipus Colonus – the play follows blind Oedipus in his exile in the final years of his life. Oedipus and Antigone are in the small village of Colonus, and Oedipus has to defend himself from the villagers, afraid that his lack of morals would bring a curse on them all. Oedipus advocates for himself, but understands that his end is near, as predicted by the oracle. King Theseus of Colonus agrees to protect him while news from Thebes opens new wounds. Oedipus’ sons – Eteocles and Polynices- are at war with each other as Eteocles had commended Polynices to exile for the attempt at usurping power. Polynices seeks revenge – and eventually this will lead to a war, killing both brothers. Oedipus interprets a sudden thunder as Zeus’ sign of his coming death, and walks away, followed by King Theseus and his children. Oedipus dies, King Theseus attends his burial and does not reveal its location to preserve the peace of the site.

Elektra – During the ten-year Trojan war that kept Agamemnon away from Argos, Clytemnestra had become the ruler of the town and had chosen a new lover in Aegisthus. When Agamemnon comes back from the war, Clytemnestra kills him with the help of her lover. She justifies the murderous act as a rightful revenge for Agamemnon’s sacrifice of their younger daughter, Iphigenia. Clytemnestra’s remaining two children, Orestes and Elektra, wanted to avenge their father and therefore became a threat to Clytemnestra. Orestes fled Argos to escape being killed, and Clytemnestra got rid of Elektra by marrying her off to a countryman, far away from Argos. As Orestes comes back and finds his sister, they plot their revenge and kill both Aegisthus and their mother, Clytemnestra, to avenge their father.

Philoctetes – the play follows the Greek warrior Philoctetes, who was abandoned on the island of Lemnos by Odysseus as they were sailing towards Troy because he suffered an infectious wound that had a rotten stench. Years later, a prophecy told the Greeks they would never win the war at Troy unless they retrieved Philoctetes’ divine bow and arrows. Neoptolemus and Odysseus then sail back to Lemnos to trick Philoctetes and steal the divine weapon. Yet, Neoptolemus gets to know Philoctetes and is ashamed of the deceitful plan. In the end, Neoptolemus asks Philoctetes to join them in the war against Troy.

Trachiniae – The play focuses on Heracles, who comes home after having accomplished the twelve labors. His wife, Deianeira is led to believe that a love potion provided by Lichas, a deceitful messenger, would make sure Heracles never leaves her side – and her family- again for any other labor of in search of a new and younger wife, so she applies said potion to a garment she gives Heracles as a gift. The love potion turns out to be a magic poison that horrendously kills Heracles. Deianeira commits suicide immediately afterwards, overwhelmed by guilt.

Euripides (480-406 B.C.)

Euripides was also a very prolific Greek playwright who is believed to have written over one hundred plays, out of which only eighteen have survived. He was less popular in his time than either Sophocles or Aeschylus, but his popularity grew later in time, which is probably one of the reasons more of his plays are widely available to this day.

Euripides’ style was less elegant than Sophocles’, and his attention to detail and structure was less specific than Aeschylus’. His text is clunky at times, his monologues repetitive, and the overall timeline of his plays is sometimes inconsistent. He also uses the apparition of the gods (the so-called deus-ex-machina) a lot, mostly to “resolve” the action that could not be resolved otherwise.

His plays focus on a wider variety of myths, some of which are lesser known. In his time, he was considered controversial, which was likely one of the reasons why he wasn’t very popular, since his plays often questioned the order of society and power. He criticized the government and introduced the idea that the gods might not have much to do with earthly matters after all. This same feature, along with his very strong characters, is what will appeal to future audiences and what makes some of his plays very popular today as well.

It is important to note that several of Euripides’ plays do not end with tragic and horrific deaths, but that doesn’t make them less of a tragedy. The genre is defined by the amplitude of the scope and of the subject matter rather than by the technicality of the ending of the play.

The eighteen plays that we know of are:

Alcestis – the play follows Alcestis, who offers herself to the god of the underworld, Thanatos, in place of her husband Admetus. When Heracles visits Admetus’ house, he learns about Alcestis’ sacrifice and ventures into the underworld to fetch her and bring her back to the world of the living.

Medea – the play is about the Medea, the young queen of a foreign country who had helped the Greek noble man Jason steal the Golden Fleece and was married to him in return, only to be abandoned by him years later when a new, younger bride would also grant him the ability to become king. Now residing in Greece, where they find her cultural differences barbarian and akin to witchcraft, she is rejected by her husband and ordered to leave the country, leaving her children behind. Instead, she uses her magic to kill Jason’s new bride, then she kills her children, leaving the city of Corinth on the chariot of the sun with the children’s corpses, while Jason mourns his losses.

Hippolytus – Because of a spell cast by the goddess Aphrodite, Theseus’ wife Phaedra falls in love with her step-son Hippolytus, but her love is unrequited. She kills herself out of shame, but leaves a letter accusing Hippolytus of having seduced her. Nothing will convince Theseus of his son’s innocence; he exiles and curses him, asking Poseidon to avenge him. As Hippolytus leaves, a divine bull unleashed by Poseidon causes the chariot to run out of control, and Hippolytus falls to his death. Learning the news, Theseus is overjoyed, believing justice has been served. Yet, the goddess Artemis appears and reveals the truth: Hippolytus was innocent.

Troyan Women – In the immediate aftermath of the defeat of Troy, the widows of the Trojan warriors are gathered outside the walls of the city, waiting to know their fate. Among them, Hecuba (King Priam’s wife), her daughter Cassandra, and Andromache (Hector’s wife) with her newborn child, Astyanax. All the women will be assigned to Greek warriors as slaves as part of the loot, but some will prefer to die rather than leave their country and be degraded.

The Bacchae – King Pentheus and his mother, Agave, ban the cult of the god Dionysus from Thebes, questioning his status as a god. Dionysus is the son of a mortal woman, Semele, and of Zeus. Yet, Agave and Pentheus believe Semele made up that story to justify her pregnancy. Dionysus is enraged and plans his revenge. He drives the women of Thebes, including Agave, into a frenzy. They leave town and go into the woods, where they wildly engage in rituals, hallucinate, kill flocks, and kidnap children. Dionysus, disguised as a mortal, suggests Pentheus wear women’s clothes to go spy on the women to find a way to stop the frenzy. Yet, when Pentheus is close to the women, the god appears to them and lets them believe he is a wild animal. Pentheus is trapped and killed by his own mother, who will carry his head back to Thebes. As the madness slowly fades away, the horror sets in.

Iphigenia in Aulis – To win the war at Troy, Agamemnon is told by a prophet he needs to sacrifice his younger daughter, Iphigenia. He summons her and her mother, Clytemnestra, deceitfully telling them the young lady will be marrying Achilles. When the scam is revealed, Clytemnestra is enraged, but Iphigenia accepts her fate. Yet, as the sacrifice takes place, a god intervenes. Iphigenia disappears and is replaced by an animal.

Iphigenia in Tauris – This play is somewhat a follow-up to Iphigenia in Aulis. Once she disappeared from the sacrificial altar in Aulis, Iphigenia was transported by Artemis to Tauris, where she became a priestess. When her brother Orestes washes ashore and is sentenced to be sacrificed, Iphigenia helps him out and they escape together.

Helen – the play is based on a variation of the myth of Helen of Troy. Here, Helen never abandoned Menelaus for Paris and never fled to Troy. Instead, the goddesses Athena and Hera sent her off to Egypt, while they sent to Troy a mere phantom of the woman. When the war is over, Menelaus shipwrecks on the coasts of Egypt and finds himself face to face with Helen, who has a lot of explaining to do. When Menelaus understands what happened, they plot their escape and flee Egypt together.

Ion – Being raped by Apollo, Creusa gives birth to Ion, but she abandons him in the wild. Apollo saves the child and brings him to his temple in Delphi. Years pass, and Ion has become an attendant of the temple. Creusa travels to Delphi to ask the god to help her conceive a child with her newly married husband. Ion and Creusa are initially unaware of being related, but in the end, they find out and are reunited.

Orestes– After killing their mother, Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus, Orestes and his sister Electra plan to kill Menelaus’ wife, Helen, out of revenge. When they’re about to do it, she vanishes, as Zeus intervenes and transforms her into a constellation. Orestes kidnaps Menelaus’ daughter Hermione, and just before the standoff with Menelaus’ men, Apollo appears and averts another bloodshed. Hermione will marry Orestes, while Electra will marry Orestes’ best friend, Pylades.

Andromache – In the aftermath of the war of Troy, Andromache, Hector’s widow, has been assigned as a concubine to Neoptolemus as part of the loot. After having her first son killed by the Greeks, Andromache tries to save her second child, conceived with Neoptolemus, but she is unsuccessful.

Hecuba – King Priam’s widow, Hecuba, loses two more children. Her younger daughter, Polixena, is sacrificed by the Greeks while her baby boy, Polydorus, washes ashore, dead. Hecuba had confided in a nearby former ally of Troy, Polymestor, to protect the child. Yet, Polymestor had killed him to please the Greeks. When Polymestor comes to the Trojan camp and meets Hecuba, she executes her revenge with the help of the other women. She kills Polymestor’s sons and blinds him.

The Suppliants – revolves around the mothers of the warriors who were killed in Thebes as they travel to Athens, the cradle of democracy, to advocate for their right to see their children buried with the due rites to the king of Athens, Theseus. The king listens, is moved, and provides support.

Electra – This play tells the story of Electra and of how she avenged her father’s murder, killing Clytemnestra and Aegisthus with the help of her brother Orestes. This play doesn’t differ much from previous renditions of the myth by the hand of Aeschylus and Sophocles. The main difference lies in the style.

The Children of Heracles – Heracles’ sons are at war against Mycenae’s king, Eurystheus. A Prophecy informs them that they would only win if a maid is sacrificed to the gods. Heracles’ daughter, Macaria, offers herself for the sacrifice, granting victory to her brothers.

Heracles – the play follows Heracles as he is driven into a frantic state by the goddess Hera. In his madness, he kills his wife and his three children.

The Phoenician Women – Jocasta, Oedipus’ wife, hopes to see her two sons reconcile and avoid the war, but she is unsuccessful. Eteocles and Polynices keep fighting one against the other, and they both die. Jocasta kills herself. This play provides a different take on Jocasta’s demise. In Sophocles’ play [Oedipus the King], she killed herself before Oedipus blinded himself. In Euripides’ version, she doesn’t commit suicide and stays in Thebes when Oedipus leaves town in exile, as a blind man.

Cyclops– this is not a tragedy, but a satyr play. The play follows Odysseus as he and his men wash ashore and are detained by the Cyclops, who intend to eat them. Odysseus plots his escape and executes it, blinding the Cyclops. It is worth noting that of all the satyr plays that were written, this is the only one that has survived.

Satyr Plays

There is evidence that points to Pratinas as the first playwright to introduce satyr plays. As we have mentioned, playwrights who wanted to be considered for the City Dionysia were asked to present a trilogy of tragedies and a satyr play, which means…. Thousands of them have likely been written. Yet, only Euripides’ Cyclops has survived, along with some parts of Sophocles’ The Trackers.

The satyr play is named after the chorus, which is populated by satyrs – half-beast beast/half-human creatures. The chorus leader (coryphaeus) was Silenus, the father of all satyrs. Satyr plays were very different in style from tragedies, although they often used the same material. First off, the language was different. There was no attempt at a heightened language, and nothing was written in verse. There was also an abundant use of foul and indecent language, mostly for comedic purposes. Because satyr plays were performed after the trilogy of tragedies, they aimed at providing the audience with some comedic relief. Most plays dug into myths, but emphasized some of the features and characters for comedic purposes. In a way, they leaned into the caricature style. They also heavily relied on dance and music.

Comedy

Comedies were also produced and performed in the City Dionysia in Athens, and they set a completely different tone from tragedies, which is quite intuitive. They also featured three actors and a chorus, like for tragedies, although the comedic chorus was much larger, featuring up to twenty-four members. Women were not allowed to act, and here, there was also the use of music and dance, although the style was significantly different from tragedies. The music and the dancing, in particular, were less composed and stylized. The dancing was often inspired by animal movements and celebrations of many sorts.

The main intent of the playwright was to entertain the audience, to make them laugh, while also providing some specific social commentary. Comedies distanced themselves from any form of realism and had a wider pool of subject matter. Some of them were set in a fantasy world, with fantasy characters, like for example The Clouds, The Birds, and The Wasps, all plays by Aristophanes (446-386 B.C.). Comedies had a fast pace, almost farcical, and at times featured characters who really existed. For example, in another one of his plays, Aristophanes makes fun of Euripides (The Acharnians).

As for style, there was no intention to use heightened language. Common elements of the plots included allusions to sex, heavy drinking, and more generally, leisurely activities. The structure is also simplified, with a prologue setting up the story and prepping for the main idea, then there is the entrance of the chorus that triggers the debate (agon) of said idea, and finally, there is the execution of the idea. In between, there is a choral ode, called parabasis, where some social or political issue is discussed, which usually has ties to the main idea.

Most of what we know about comedies comes from the plays that have reached us, which happen to be written by only one playwright: Aristophanes.

Aristophanes was not the most prolific playwright, in particular if we compare him to Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. He is believed to have written around forty plays, out of which only eleven have survived. They are: The Clouds, The Knights, The Wasps, The Birds, Lysistrata, The Frogs, The Acharnians, Peace, The Women at the Thesmophoria, The Assembly Women, and Plutus.

Aristophanes’ plays are still very popular today and are frequently produced; below is the synopsis of some of the most popular ones.

Lysistrata – the play is a social commentary on the Peloponnesian War, which saw Athens fighting against Sparta for many, many years. In the play, the women decide to undergo a sex strike to stop the war. In other words, they wouldn’t satisfy their husbands’ needs unless they stopped fighting. As you can see, the motto “make love not war” is grounded in Lysistrata, a play written in 411 B.C.! An element that adds more comedy to the plot is the fact that, because women were not allowed to act: as such, their roles were played by men. The play also featured male characters – the husbands-, who at some point dress up as women to go spy on their wives. That makes for yet another, very comedic, element.

The Frogs – The play features Dionysus heading down to the underworld in disguise to bring Euripides back to life. He finds him “dueling” against Aeschylus to determine who was the best writer of tragedies. Dionysus decides that the winner will be brought back to life, but both playwrights do well, and that makes his decision very difficult. He then says he will bring back to life the one who will give the best advice on how to save Athens (from the wars). Aeschylus wins. The Frogs has been adapted into a musical by the same name, authored by Stephen Sondheim.

Peace – in another anti-war play, where a middle-aged Athenian Tygaeus succeeds at ending the Peloponnesian war by visiting the gods and getting peace, set free from the cave where she was kept. The war ends, and many Athenians are overjoyed, while those who profited from the war are unhappy with Tygaeus.

Costumes

There is very little evidence about what kind of costumes were utilized in Classic Greek theatre, in particular when it comes to tragedies.

Some believe that actors would wear a decorated tunic, called chiton, with maybe a short cloak, the chlamys, or a long one, the himation, to go on top of it. Actors apparently wore platform shoes, called kothornos, with laces coming up to their calves. Other scholars argue about the existence of more complex costuming, tailored to the needs of a specific production. Yet, nothing has been proven for certain. What we know mostly comes from some painted fragments of vases and pottery.

As for comedies, apparently, they allowed for a less elegant or stylized approach to costuming. It is believed both the actors and the chorus would use garments that were adapted from everyday clothes, with the occasional addition of grotesque elements to add to the comedic effect. Sexual attributes, such as the penis, the bottom, and female breasts were exaggerated and added to the costumes as well. On many occasions, the comedic chorus is populated by animals, for example, in Aristophanes’ The Frogs. In that case, costumes would try to provide an idea of the animal as well.

How did the Greek Theatre respond to its society?

The tragedy Trojan Women, written by Euripides and produced in 415 B.C., is a direct response to the Siege of Melos (the current island of Milos), during the Peloponnesian Wars of 416 B.C., where Athens invaded the island, killed, and enslaved its population. While the playwright could not directly attack the Government, the Greeks did indeed introduce “democracy” [demos=people + cratos= power, power to the people], but it was not exactly the same concept of democracy we have today. He wrote about the aftermath of the Trojan War, when the Greeks set Troy on fire, killed all the men, and enslaved the women, assigning each one—including the widows of the king and the warriors—to Greek commanders and warriors. For example, Hecuba, the wife of King Priam, was assigned to Odysseus, and her daughter Cassandra to Agamemnon. In a famous passage, Taltybius, the Greek messenger, announces to Hector’s widow, Andromache, that she must relinquish her newborn child to the Greeks because he has to be killed. The Greeks feared that once an adult, the baby boy would seek revenge.

Below are a couple of famous quotes from the play, and as you can see, while they are directly connected to the plot of the play, they do lend themselves to a more generalized and universal criticism about the Greeks.

Andromache: You Greeks have invented savage new crimes:

Why are you killing this innocent baby?

(V 764-765)

Hecuba: You, Achaeans, have greater pretense at the spear

than sense. Why, in fear of this child, have you

committed a new murder? (V. 1158-1160)

Achaeans, your spears weigh more than your judgement,

Why, you are afraid of a child, and therefore, you commit murder.

Another example of how theatre commented on society is well presented in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata. Research exercise: read the play and find the connection between the text and its social commentary.

Music in Greek Theatre

Classic Greek plays used a ton of music, including instrumental pieces and songs, as an element of spectacle and to emphasize the relevance of certain concepts. The Greeks, in fact, believed music had some ethical qualities, in particular when played to highlight a specific idea or emotion. Unfortunately, very little has survived of the original scores. There are a few fragments, but nothing as extensive as to allow us to reconstruct the score of any play in its entirety.

The instruments that we know were utilized are the flute, the lyre, the trumpet, as well as a variety of percussion instruments. Musicians played alongside the chorus, likely sitting closer to the audience.

Who is the Greek Hero, or the Tragic Hero?

The Greek Hero, or Tragic Hero, in a Classic Greek tragedy is the protagonist of the play. Nowadays, the term “hero” carries various meanings and immediately brings to mind over-the-top characters who fight— and mostly win—against inconceivably tough circumstances to “save the world.” When it comes to Classic Greek theatre, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

In a Classic Greek tragedy, the Greek hero is always a male character of noble birth – as it had to be someone the audience looked up to, someone who could set an example. He, like everyone, isn’t perfect and therefore makes a mistake due to a character flaw, also known as hamartia. That mistake is at the core of the tragedy and sets in motion the hero’s demise. Yet, what makes the character a hero is that he ultimately understands his mistake, takes responsibility for his actions, and bears the consequences of them.

For example, in Sophocles’ Antigone, the tragic hero is Creon, Antigone’s uncle. His tragic flaw is his pride, or hubris. While he believes he is doing what is best for Thebes, he is too proud to listen to other people’s advice and ultimately refuses to admit he is wrong. By prioritizing the state over his own family and condemning Antigone to death, he loses the support of the people as well as his son, who commits suicide. He loses everything. He will live bearing the consequences of his actions, becoming the living example of what happens when we are too proud to accept the advice of others.

In Euripides’ Medea, the tragic hero is Jason, whose hamartia is ambition. Because he is not content with his social standing, he rejects his wife and abandons his children to marry the daughter of the current King of Corinth and advance his social status. This triggers Medea’s revenge, as she first kills Jason’s soon-to-be new bride and the king, and then kills her and Jason’s children. Once again, Jason is left with nothing. Medea even carries away the corpses of his children, so that he wouldn’t have the opportunity of providing them burial rites and properly mourn them.

Theatrical Spaces and Design Elements

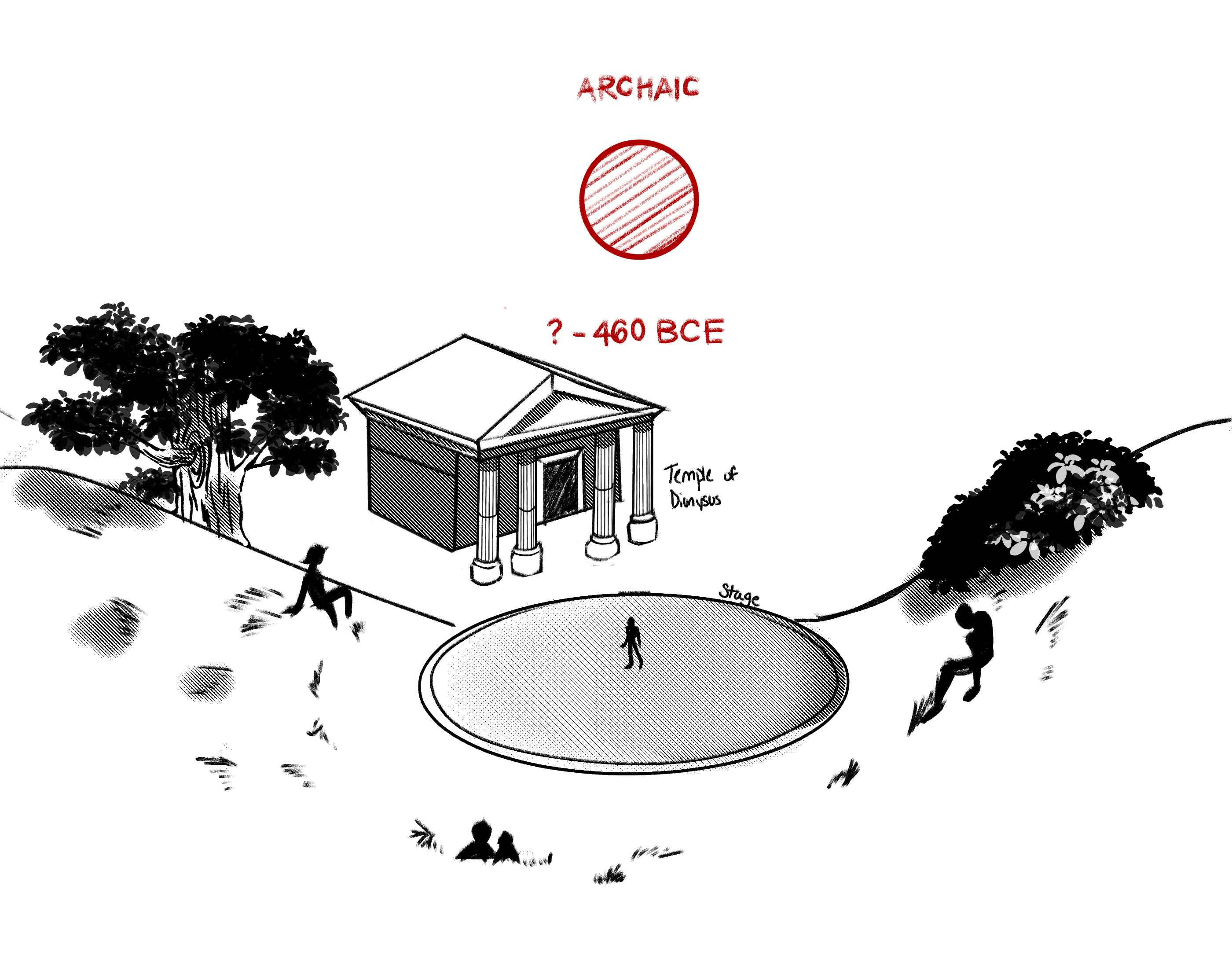

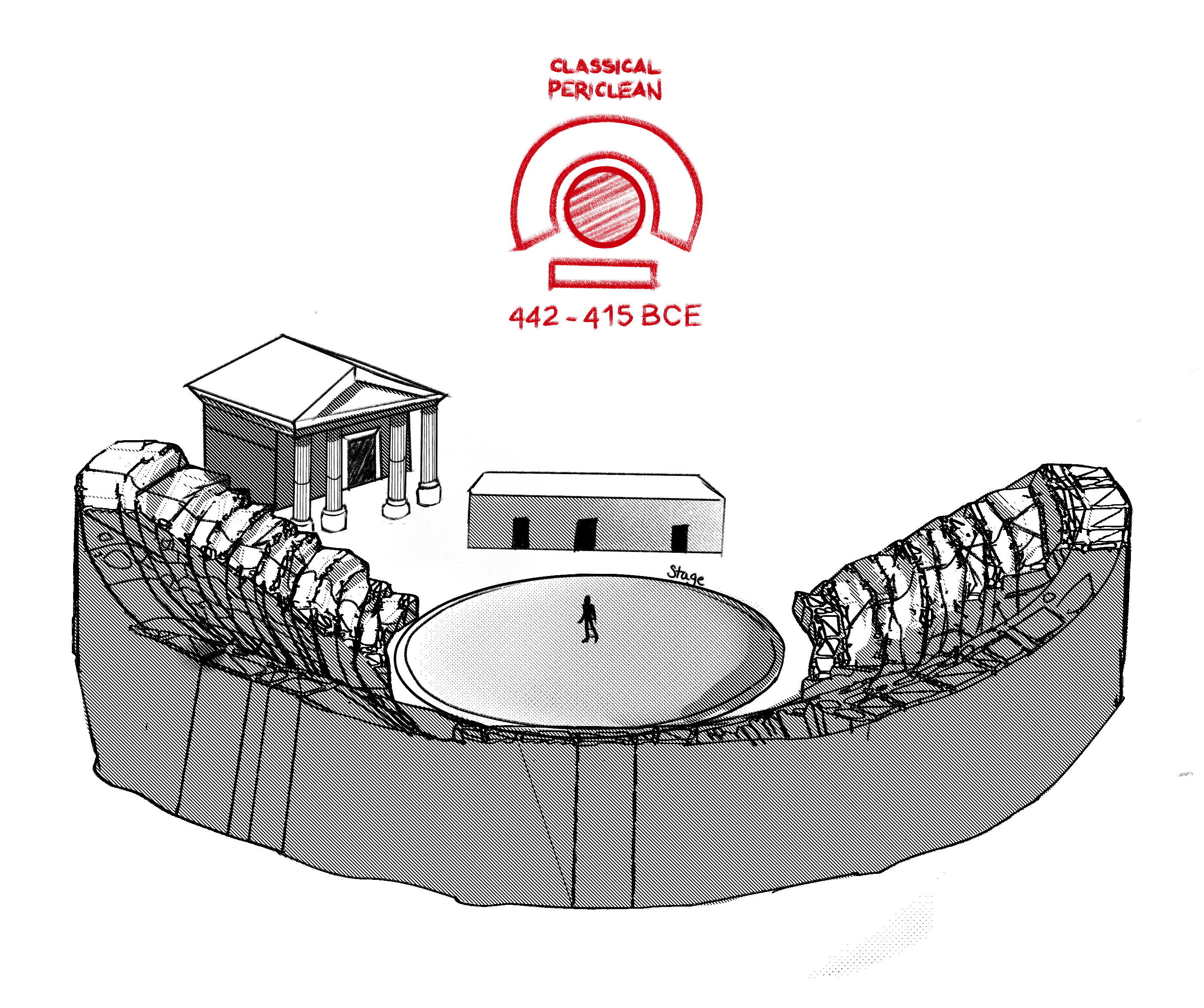

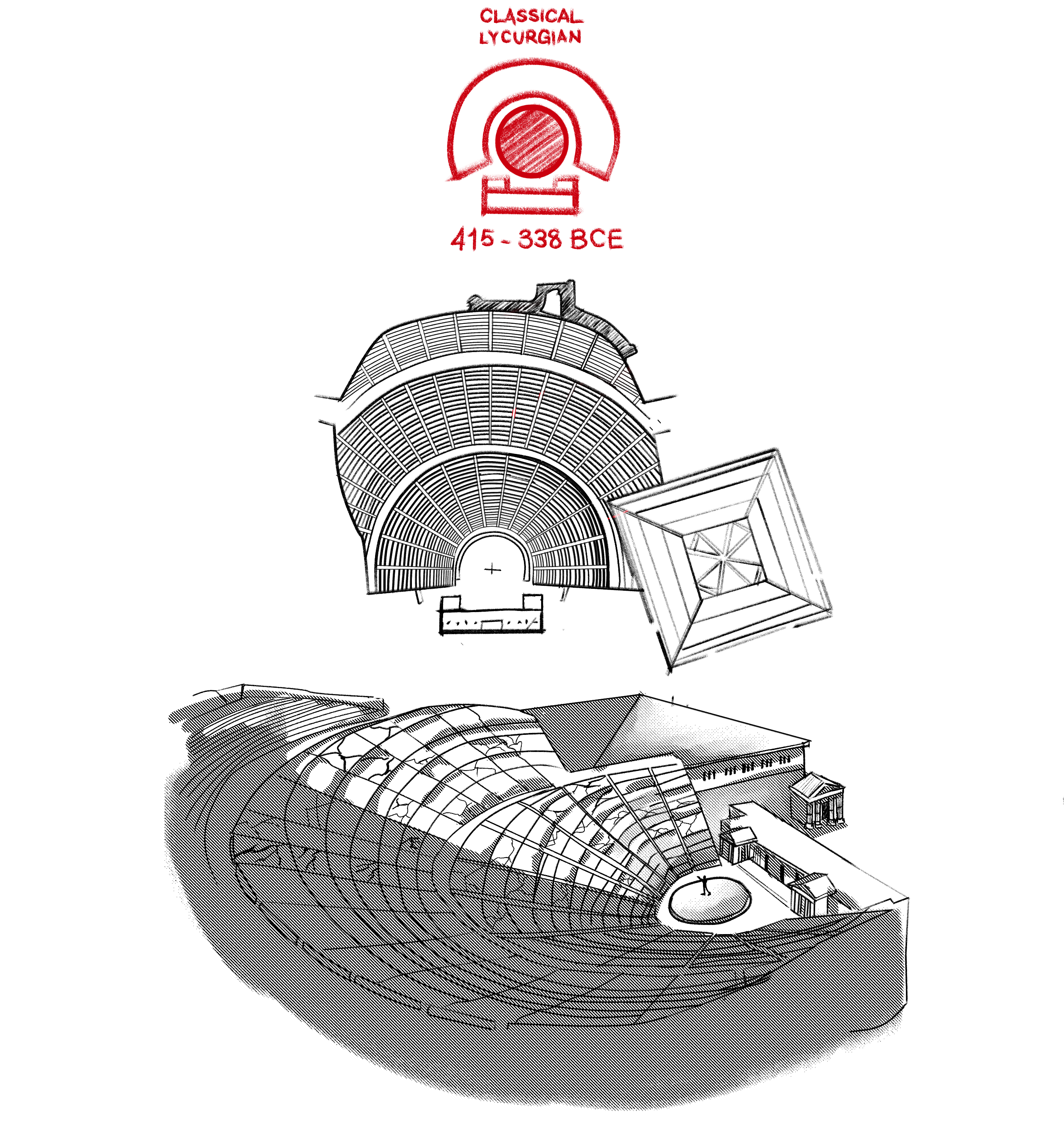

Athens featured one of the biggest theatrical spaces in Greece, the Theatre of Dionysus. It is located at the bottom of the Acropolis, in the sacred area dedicated to the cult of the god.

The theatre evolved greatly throughout the centuries, so tracing back its origins can be quite challenging.

Likely, at the end of the 4th Century B.C., there wasn’t much of a structure per se. The main area was a circular space called the orchestra, located at the bottom of the slope known as the theatron. There was a sacrificial altar somewhere in the orchestra, possibly in the center.

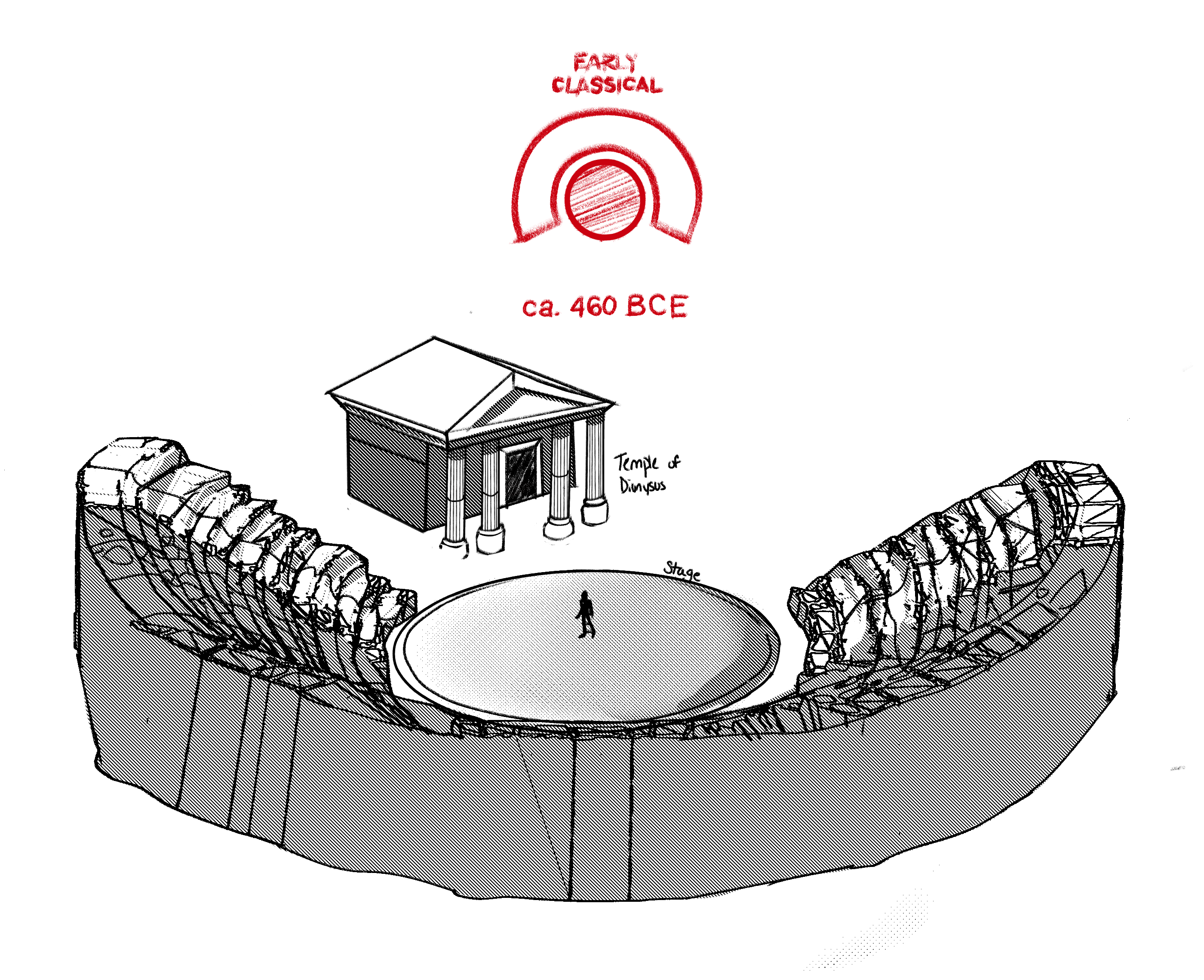

The chorus would reside in the orchestra. The actors would probably be standing on a wooden platform on the opposite side of the slope, tangent to the orchestra. The audience would sit on the natural slope of the land. Initially, there wasn’t much of a dedicated seating area, but around 498 B.C., wooden benches (ikaria) were added, and the theatron was shaped into terraces to facilitate seating.

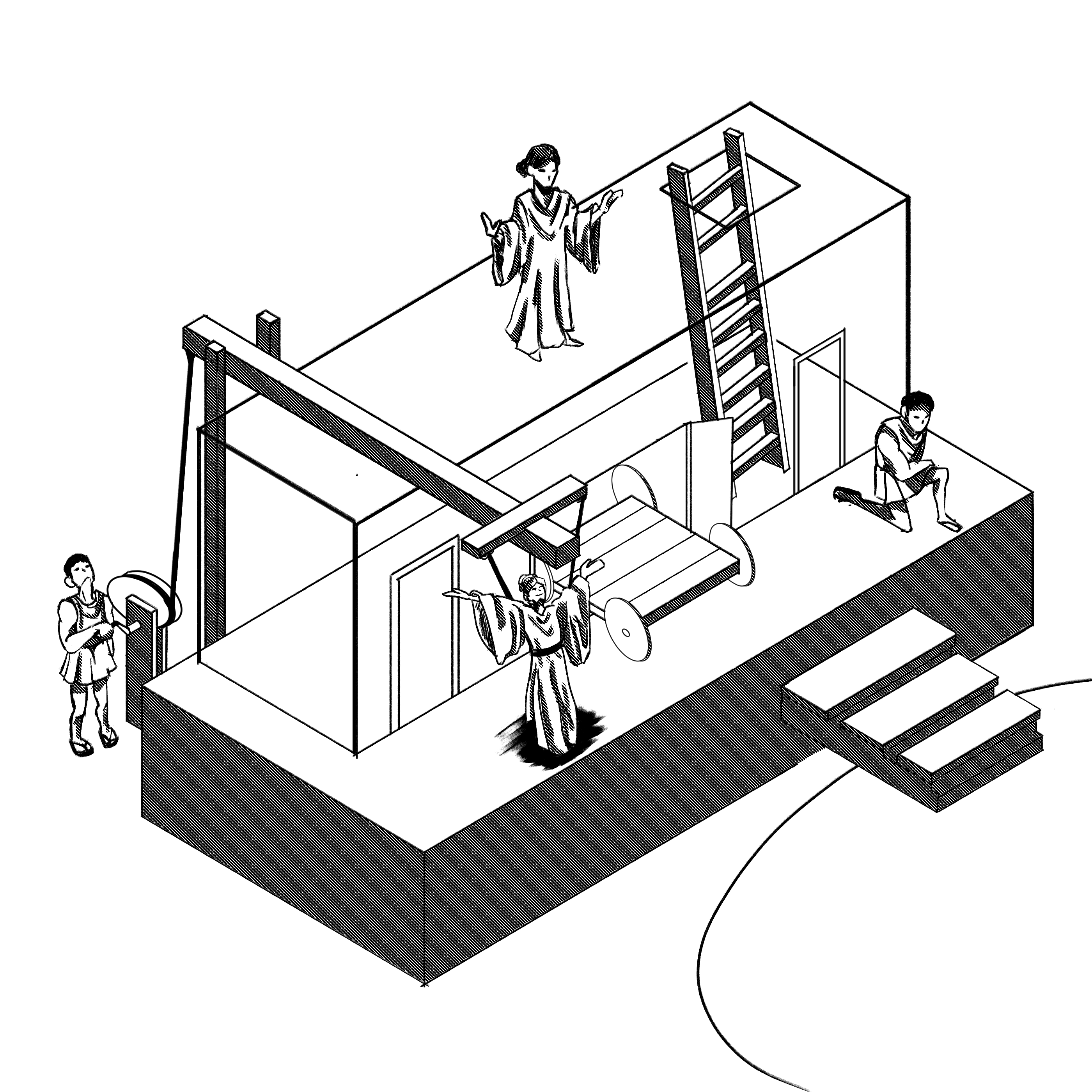

Next (5th Century B.C.) was the addition of the stage building, also called skene. It was originally a simple wooden structure with three doors, a wider one in the center, and two smaller ones on the sides. The central door was devoted to the entrance of the most important characters, while the side doors were for the minor characters and the messengers. The roof of the skene was utilized for the apparitions of the gods or other special effects.

It is assumed that originally the skene was a temporary structure, being built specifically for the City Dionysia every year. Later, it became a permanent, stone building. Either way, it represented the backdrop for all of the production, and it started to be decorated around 460 B.C., which is when both Aeschylus and Sophocles were active.

At the top of the performance, the actors and the chorus would enter from the parodoi (parodos, singular), two aisles at the side of the skene at the bottom of the slope.

At the end of the 5th Century, the wooden benches were substituted by stone seating, and finally, the skene was also built in stone.

The seating area was called koilon, and as the theatre grew in popularity and required more seating, it was divided into two different sections by a middle aisle, the diazoma.

The seats closer to the orchestra were for the notable citizens of Athens, and members of the polis would also have dedicated seats, known as the proedria—small throne-like chairs positioned directly above the orchestra.

At the peak of its popularity, the Theatre of Dionysus would seat about 17,000 people. Tickets had different prices, depending on the location of the seat. Pericles had also established a fund to allow poor people to have access to tickets. All the money coming from ticket sales would go towards the upkeep of the theatre.

The Theatre of Dionysus kept growing all throughout the Hellenistic times and with the Romans as well, gaining seats and a building at the back of the skene. Containment walls had to be built as well, in order to secure the seating area.

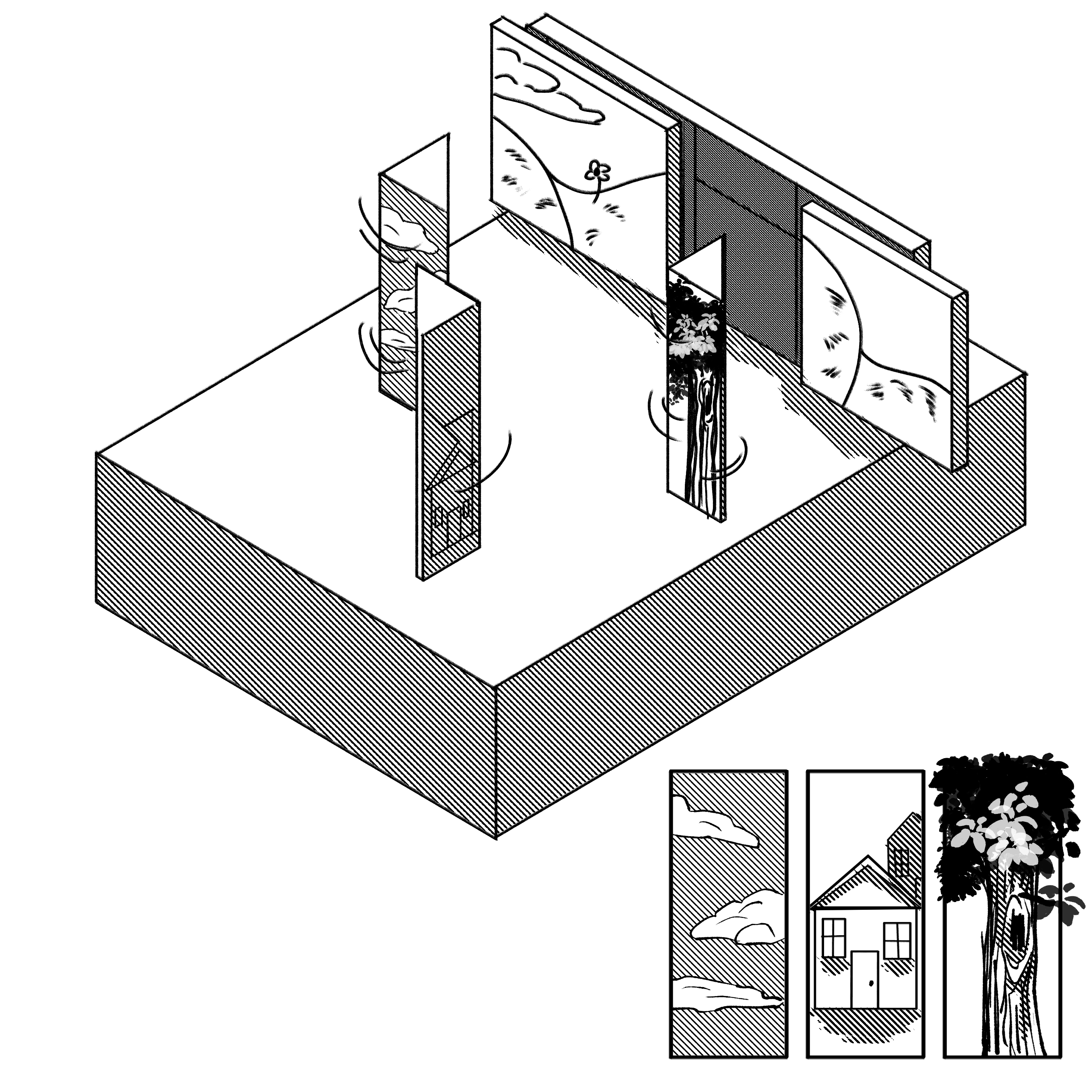

When it comes to scenic design, there are a few elements that are believed to be popular. Pinakes, for example, were wooden panels that could be painted according to the needs of the play. They could be switched during the production thanks to in-ground ridges in front of the skene. Another scenic element was the periaktoi, triangular prisms that could rotate on a central pivot, showing a different design on each side. They were located on the side of the skene. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to claim that these elements were surely used in the 5th Century B.C., but we do have records of them being used later.

Another important scenic element was the ekkyklema, a small platform on wheels that could be pushed in and out of the main door of the skene to create a surprise effect.

Lastly, there was the machina, a crane of some sort that sat behind the skene, allowing for characters or elements to be lifted, thus appearing as though they were flying. This would have been necessary, for example, at the end of Euripides’ Medea, when the Chariot of the Sun takes Medea and the corpses of her children away from Corinth. Many of Euripides’ plays seemed to have benefited from the machina as a way to resolve the play with spectacle.

And this is what originated the Latin expression deus-ex-machina – literally, “god out of the machine”- as a way to abruptly put an ending to a play, without leaving space for a proper dramaturgical resolution.

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.)

In the Poetics (335 B.C.) Aristotle investigated the social and educational value of theatre. He considered tragedies as the prime genre, and comedies not to be morally relevant. He considered Sophocles’ Oedipus the King the perfect example of a good play, and as he analyzed it, he emphasized the elements that contribute to its greatness. They are the following:

Plot (mythos)

Melody (melos)

Characters (ethos)

Language (lexis)

Spectacle (opsis)

Thought (dianoia)

For a play to be good and educational, it needed to have a compelling plot (in Greek, mythos), a story that needed to be told. Oedipus the King portrays this well, telling the story of a young man who tries to defy his destiny. Thanks to his intelligence and good nature, Oedipus becomes a King only to experience a ruinous downfall that will force him to accept his fate and become the living example of his wrongdoing.

Melody and language are also important elements. Melody can be achieved with music as well as with the rhythm of the language. Classic Greek tragedies used verse, which gave the speech rhythm and rhyme. They also had music in them – with dancers performing in the orchestra.

According to Aristotle, characters needed to be of noble birth to help the common citizen learn a lesson. If someone above their status made a mistake, recognized the mistake, and accepted their punishment, that character would be a good role model. The argumentation highlighted in the dialogue would make the protagonist’s personal journey more believable.

Finally, in order to keep the audience engaged, Aristotle recognized that some form of spectacle needed to be present. This could be achieved through dancing or by the ghostly appearance of a God.

How did the audience learn from the play, and what did they learn?

According to Aristotle, the play presented a setup—a scenario, in which a powerful character, the Greek hero, makes a mistake, due to a personal flaw. In the case of Oedipus, his tragic flaw was his arrogance, which led him to believe himself to be smarter than the gods. Once the mistake is committed, a chain of events will lead the character to face the truth and realize that they were wrong and must take responsibility for their actions.

Because the tragic hero, like Oedipus, is a man of integrity, who does not intend to harm but seeks to prevent a greater evil—and because he proves to be a good ruler—the audience follows his downfall with sympathy. The audience undergoes what is called “catharsis”, an emotional release which allows them to better understand the resolution.. As the audience walks out of the theatre, they have learned that trying to deviate from the order of things is wrong, and that punishment will come regardless of social status. Even a king cannot escape his fate.

Adaptations of Classic Greek Myths/Tragedies

There are countless later adaptations of Greek classic plays and myths. Because of the universality of the topics they explored, plays such as Medea, Antigone, Oedipus Rex, the Oresteia, and Helen, just to name a few, have been and continue to be revisited in the modern age. Some of them have even been adapted into operas and musicals.

For the most part, adaptations explore tragedies, but there are also a few adaptations of some of Aristophanes’ other works, mostly of Lysistrata and The Frogs. Below you will find a short list of them, as an example. You could find many more titles with a brief research.

As the 17th Century Europe rediscovered the classics, also thanks to translations from Greek into Latin finally being available, several playwrights revisited some of the Greek plays. It all started with the fall of the Roman Empire in the East, in 1453, when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople. As a result, scholars fled to Italy and France, carrying with them the manuscripts of the Greek Classics. This marks the beginning of the European exposure to Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus. Greek works were then published in their original language and later translated into Latin.

Access to these works was mostly for the most educated and wealthy, yet soon enough, their circulation improved, leading to a significant evolution in European theatre and literature in general.

Below is just a sample of adaptations of classics from the 17th Century onward.

Two French playwrights, Pierre Corneille (1606-1684) and Jean Racine (1639-1699), wrote several.

Pierre Corneille wrote: Médée (1635), Oedipe (1659), La Toison d’Or (1660. This is based on the myth of the Golden Fleece, and features Medea and Jason as main characters. In this version of the myth, Jason does not marry Medea and leaves her in her homeland),

Jean Racine wrote: La Thébaïde (1664, based on Antigone), Andromaque (1667), Iphigénie (1674), and Phèdre (1677)

In England, roughly in the same period, John Dryden (1631-1700), who was mostly known for his comedies, wrote a gruesome adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, titled Oedipus (1679).

In the 18th Century, Germany, Goethe (1749-1832) wrote Iphigenia in Tauris (1779), later Franz Grillparzer wrote The Golden Fleece (1821), and Hugo Von Hofmannsthal wrote Elektra (1903).

Modern and contemporary adaptations include:

Andre Gide – Philoctète (1899), Oedipe (1931).

Bertolt Brecht – Antigone (1948).

Jean Anouilh – Antigone (1944), Medea (1953).

Heiner Müller – Philoctetes (1968).

Derek Walcott – Ione (1977) The Isle is Full of Noises (1984, based on Sophocles’ Philoctetes).

Rita Dove – The Darker Face of the Earth (1994, based on the myth of Oedipus).

With the larger availability of texts thanks to, amongst other things, the internet, the proliferation of classic-inspired texts has grown exponentially in the course of the latter part of the 20th Century and continues to these days. Selecting adaptations of the classics becomes a futile endeavor; hence, what you will find below is just a sample to provide an idea of the scope of the work.

Christopher Durang and Wendy Wasserstein– Medea (1994, a tragicomedy in one act)

Seamus Heaney – The Cure at Troy: a Version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes (1990) and The Burial at Thebes: a Version of Sophocles’ Antigone (2004).

Neil LaBute – Bash: Latter-Day plays (1999, three short plays investigating Iphigenia and Medea).

Luois Alfaro – Electricidad (2003, based on Sophocles’ Electra), Oedipus El Rey (2010), and Mojada (2013, based on Medea).

Some musicals include:

The Gospel at Colonus – score by Bob Telson, book and lyrics by Lee Breuer, based on Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus. It first opened off Broadway in 1983. It opened on Broadway in 1988.

Marie Christine – score, book, and lyrics by John LaChiusa, based on Euripides’ Medea. It opened on Broadway in 1999.

Lysistrata Jones – book by Douglas Carter Beane, score and lyrics by Lewis Flinn. It opened on Broadway in 2011.

While Shakespeare could not have access to Greek classic plays, as they hadn’t been translated yet, he was familiar with the Greek myths as they were reported by Roman historians and playwrights. His play Troilus and Cressida, for example, is based on the Trojan Wars.

TAKEAWAYS – GREEK THEATRE

Thespis is the first actor/playwright we have records of, and he invented the tragedy by introducing dialogue in the 6th Century B.C.

Theatre was part of the rituals in honor of the god Dionysus.

Originally, tragedies had one actor interacting with the chorus. Later, Aeschylus added another actor, and Sophocles added a third one.

Sophocles also set the number for the chorus to fifteen members.

The plays were produced within a festival, the most important of which was the City Dionysia, in Athens.

The City Dionysia presented a trilogy of tragedies and a satyr play per playwright. Later, comedies were also produced.

The “golden age” of classic Greek Theatre is the 5th Century B.C.

The most famous playwrights of the period – and the only ones whose work has survived – are Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, who wrote tragedies, and Aristophanes, who wrote comedies.

In 335 b.C Aristotle wrote the Poetics, a treatise where he discusses theatre, its social function, and analyzes the structure of what he considers a good play (Sophocles’ Oedipus the King)

The Theatre of Dionysus was located at the bottom of the Athenian Acropolis and was where the City Dionysia took place. The theatre greatly evolved from the 6th to the 4th Centuries and beyond. At the peak of its popularity, it could seat 17,000 people.

Classic Greek plays are still very popular for the universality of their subject matter.

Vocabulary

Aristotle

Poetics (Ars Poetica)

Abydos

Osiris

Crete

Minoan civilization

Knossos

Rigveda

Buddhacarita

Mahabharata

Ratnavali

Aztecs

Maya

Flowery War

Rabinal Achi

Thespis

Theatron

Dithyrambs

Tragos

Mimesis

Dionysus

City Dionysia

Rural Dionysia

Lenaia

Polis

Archon

Choregus

Theatre of Dionysus

Odeon

Tragedy

Comedy

Satyr Play

Aeschylus (plays)

Sophocles (plays)

Euripides (plays)

Aristophanes (plays)

Prologue

Parodos

Exodus

Stasima

Episodes

Pollux, Onomasticon

Catharsis

Pratinas

Chiton,

Chlamys

Himation

Kothornos

Tragic hero

Hamartia – tragic flaw

Koilon

Ikaria

Orchestra

Altar

Proedria

Skene

Koilon

Diazoma

Pinakes

Ekkyklema

Periaktoi

Machina

Deus-ex-Machina

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

Let’s recreate a Greek agon (a disputation)!

Divide the students into four groups of four people.

Group 1- The group represents Aeschylus. Each student needs to read one of Aeschylus’ plays, preferably Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides, or Prometheus Bound.

Group 2 – The group represents Sophocles. Each student needs to read one of Sophocles’ plays, preferably Antigone, Oedipus the King, Electra, and Philoctetes.

Group 3 – The group represents Euripides. Each student needs to read one of Euripides’ plays, preferably Medea, Trojan Women, Orestes, and Iphigenia in Aulis.

Group 4 – The students in this group will be the jury. They will have to read a play by each of the playwrights, but not any of the ones read by the other three groups. For example, they could read Aeschylus’ The Suppliants, Sophocles’ Ajax, and Euripides’ Alcestis. All the students in this group should be familiar with the three plays, so that they will have a better idea of the differences between the three playwrights.

Groups 1,2, and 3 have to advocate for their playwright and make the argument that he is the best Greek playwright. The students’ arguments need to be based on the style, the storyline, the characters, the social relevance of the pieces they have read, and on how relevant they are still today.

The students in group 4 will listen to the other groups’ arguments, and then they should challenge each group with some questions coming from their acquired knowledge of each playwright.

The debate should conclude with the determination of who is the best classic Greek playwright.

(For the instructor: this exercise is based on the assumption that the class is capped at 16. If the number of students differs, adjustments in the group should be made accordingly.)

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| c. 3000–1100 B.C. | Minoan & Mycenaean Civilizations | The Minoans (Crete) and Mycenaeans (mainland Greece) laid the foundation for Greek culture, trade, and early writing. |

| c. 1100–800 B.C. | Greek Dark Ages | Collapse of Mycenaean civilization; loss of writing and decline in population; oral traditions like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey emerge. |

| c. 776 B.C. | First Olympic Games | The start of a pan-Hellenic tradition, reinforcing Greek identity and competition among city-states. |

| c. 750–700 B.C. | Homer Composed The Iliad and The Odyssey | Marks the emergence of Greek literature and mythology, influencing Greek identity and values. |

| c. 621 B.C. | Draco’s Law Code (Athens) | First written law code in Athens; extremely harsh, but established the principle of law over personal vendettas. |

| c. 594 B.C. | Solon’s Reforms (Athens) | Abolished debt slavery and laid the foundation for democracy by reorganizing political structures. |

| c. 508 B.C. | Cleisthenes Establishes Athenian Democracy | Introduced democratic institutions, expanding citizen participation in government. |

| 490 B.C. | Battle of Marathon | Athenian victory over Persia proved the strength of Greek city-states against larger empires. |

| 480 B.C. | Battles of Thermopylae & Salamis | Leonidas and 300 Spartans make a legendary stand; the Greek naval victory at Salamis turns the tide against Persia. |

| 447–432 B.C. | Construction of the Parthenon | Symbol of Athenian power and the height of Greek classical architecture under Pericles. |

| 431–404 B.C. | Peloponnesian War | Prolonged conflict between Athens and Sparta led to Athens’ decline and Sparta’s short-lived dominance. |

| 399 B.C. | Trial and Death of Socrates | Socrates is sentenced to death, marking a crucial moment in philosophy and the struggle between democracy and individual thought. |

| 336 B.C. | Alexander the Great Becomes King of Macedon | He began his conquests, spreading Greek culture throughout the known world. |

| 323 B.C. | Death of Alexander the Great | Marks the end of the Classical Greek period and the beginning of the Hellenistic Era. |

| 146 B.C. | Roman Conquest of Greece | Greece falls under Roman rule, though Greek culture remains highly influential in the Roman world. |