3 Chapter Three – 6th-16th Centuries European Theatre

Chapter 3 -6th/16th Centuries European Theatre

Introduction

Discussing the Middle Ages in the Arts and Theatre is a very controversial topic, since scholars disagree on just about everything. This happens because, while there is quite a lot of evidence that has survived, a lot of it is contradictory in nature. Moreover, each country in Europe experienced different social and political occurrences, which significantly determined the evolution of the arts in general, and of theatre specifically. In some instances and countries, Medieval practices morphed into the new aesthetic of the Renaissance. In other countries, they lingered for a longer period, effectively delaying the rise of the Renaissance. And in some cases, there was an overlap between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, where the two cultural and artistic trends coexisted.

This chapter will provide an overview of the theatrical practices and their evolution between roughly 900 A.D. and as late as the 16th Century. Scholars divide the Middle Ages into two periods: the Early Middle Ages (from 500 to 1000 A.D.) and the High Middle Ages (from 1000 to 1500). Some scholars prefer to call the Late Middle Ages the time between the 14th and the 16th Centuries, as that is clearly when there is overlap with the Renaissance.

In the past, the Middle Ages were also called the Dark Ages, as the belief was that with the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 A.D.) and the turmoil that ensued in Europe, survival was everyone’s main goal, leaving culture and the arts in a disadvantaged position. This viewpoint has been completely debunked, which might be the only thing contemporary scholars agree on when it comes to the Middle Ages! Although indeed, the lack of governance (particularly in the Early Middle Ages) determined a significant adjustment in society, the arts and culture were cradled and honed, and the seeds that were planted would later determine the blossoming of the Renaissance.

As a rule of thumb, we can say that the fall of the Western Roman Empire gave way to invasions and wars to assert power over the individual European countries. Quite predictably, wars lead to a general impoverishment of the population and to the deterioration of the quality of life. The wealthiest fled cities and towns – as those tended to be the target of most of the violence and looting — in favor of the countryside, where they were somewhat more protected and could rely on their land to sustain themselves. Trade became more difficult and dangerous, which led to a general shortage of goods and a spike in prices. The plague(s) didn’t help, and neither did the famines that followed.

During their tenure, the Romans enforced the use of Latin as the official language of the empire. Coincidentally, Latin also became the language utilized by the Church for functions and in holy scriptures. Monasteries became the main cultural centers of the Middle Ages, as they studied, preserved, and eventually translated the works of most Greek and Roman scholars, first into Latin and later in the vernacular. Later in the Middle Ages, monasteries were replaced by the newly formed universities, which developed at a time when cities and towns regained some footing.

With the empire gone, Latin was no longer enforced, and the people moved more steadily towards speaking the vernacular, which would eventually become the national language.

This is quite significant when it comes to the development of theatre (and of literature in general). Roman plays were written in Latin and were mostly meant to be read rather than being fully staged. With fewer people able to read and speak Latin, and cities being depopulated, conventional theatre came to a halt. Yet, theatre itself did not disappear altogether: it morphed into a variety of outlets that better suited the rising needs of society.

In the end, we always go back to the fundamental questions: what is theatre, and what is its function?

We have theatre every time someone – preferably an actor- stands in front of an audience (as small as one person!) and tells a story that springs out of an artistic intent.

Theatre can speak to the universal nature of mankind, bridging cultures and periods, and can specifically respond to the needs and issues of its time.

Between the early 500s to 900 A.D. theatre provided the opportunity to “take a break” from everyday life thanks to the performances of traveling troupes that relied mostly on physical theatre, comedic skits, circus games, and other forms of storytelling, which were pretty much a heritage of the Roman mime. Some pagan festivals still happened, and they would attract most of these theatre artists. The Church did not approve of those forms of entertainment, but its ban was difficult to truly be enforced.

In Eastern and Northern Europe, where the Roman influence had been weaker, the figure of the “scop” became popular. The scop was the German/Teutonic version of the jester, who might be at the service of a noble family or a traveling artist. He was a musician, a singer, a storyteller, and a poet, his stories would mostly rely on local mythology – hence, not Classic — and heroes.

Conversely, Medieval theatre also served the needs of the Church in various ways, and we will develop this shortly.

The lack of centralized governance — as had been provided by the Roman Empire — is what triggered the Church to substantially “step in” to provide some structure to the overall chaos. This is very important, as the Church ended up becoming the main catalyst for the evolution of culture and of the arts well beyond the Middle Ages. For a brief period, there was also an attempt at a stronger socio-political model, with the crowning of Charlemagne as the Emperor of the newly formed Holy Roman Empire (800 A.D.). Charlemagne was a lover of the arts and promoted them vicariously. Yet, his reign only lasted until 814, when he died.

Hrosvitha – by Caterina Mordeglia

Hrosvitha (935-1001 A.D.) of Gandersheim was a canoness, which is a nun who does not necessarily have to live in a monastery and has less strict life obligations. She lived in Saxony, the present-day Germany, and attended the imperial court of Otto I.

Hrosvitha is a woman who writes about women, which was unusual in the Middle Ages, as women were largely considered an emanation of the devil (ianua Diabli = “the devil’s door,” with an obscene allusion). She is the first known female playwright in history.

She wrote eight hagiographic poems, two historical works (a biography of Otto I and the history of the monastery of Gandersheim, where she mostly lived), but above all six dramatic dialogues in rhymed prose (Abraham; Dulcitius; Calimachus; Paphnutius; Gallicanus; Sapientia). Hrosvitha wrote all of her works in Latin.

Hrosvitha aimed at somewhat rewriting Terence’s six comedies to promote a new image of women, opposed to the one in the Latin poet’s original works. Specifically, she mentions in the preface of the collection of her plays that she wanted to “glorify the Christian virgin.” Hrosvitha, like most scholars of the time, had access to most of the Roman texts and was quite fond of Terence. Yet, the nature of Terence’s plots would conflict with the ethical models preached by the Church. Hence, she also aimed at providing a “new version” of his plays that could serve an educational purpose. From Terence, Hrosvitha borrows the dramaturgical mechanism while vastly modifying the plot source material and the characters. Moreover, her plays were likely not written to be performed or staged, but rather to be dramatized and read at the emperor’s court.

As of today, her plays tend to receive staged readings rather than full-blown productions.

The protagonists of Hrosvitha’s plays are no longer the prostitutes (meretrices) of Latin comedy, devoted to free love, but rather young Christian virgins who resist the devil’s temptations and the threats of powerful evil men at the cost of sacrificing their own lives to preserve their virtue. In her worldview, virginity becomes the instrument of emancipation against male power. This is a very strong Christian message, which is in line with the preachings of some Fathers of the Church – St. Jerome, for example.

Recent interpretations of her work – and herself as an artist — aligned it with a more radical feminist approach and highlighted lesbian undertones (as for example in 1973, Rita Mae Brown’s novel Rubyfruit Jungle). Yet, those claims don’t seem to be truly supported.

Early Middle Ages

Liturgical theatre

As the Church gained footing in establishing its organizational, educational, and cultural model, theatre started to be re-integrated and considered a potential asset.

Most scholars agree on the theatricality of religious ceremonies and rites, and this stands true for Medieval Christian functions and processions as well.

Every day life was punctuated by church events: it was a way to keep the congregation engaged and devoted. Special religious occurrences were celebrated with specific services and processions, both of which had theatrical value and somewhat relied on spectacle and audience participation.

The Christian church had several kinds of services, out of which the most “rigid” was the Mass itself. Yet, all other services – such as the Hours, for example – provided a good opportunity to incorporate a theatrical element in the rituals. And this is how Liturgical Drama came to be, and it is safe to say that by the 9th Century A.D., the genre had fairly extensively developed all throughout Europe. The Easter service and procession were the most popular events, allowing for such performances.

Liturgical “plays” were quite short, based on stories from the bible and featured mostly songs and music. Most of these performances were based on the visitation of the three Marys to Jesus’ tomb, which makes sense as the prime occasion for those tropes was, indeed, Easter. Later, some passages in prose were added to the structure of the trope to add to a greater dramatic component. They all used Latin. All of those “plays” (or tropes) were performed inside the church, or within holy buildings such as monasteries and convents. They would move outside later in the 13th Century. Their purpose was mostly to educate the young clergy, as they were not performed for a general audience. It was only later, between the 10th and the 13th Centuries, that we have records of them being performed for the congregation, either inside the newly built bigger cathedrals, or right outside of them.

Performers were members of the church, such as monks or choirboys.

There are several plays that have survived, although today they are only considered for scholarly purposes and not for production. As mentioned above, most of the texts were inspired by Christ’s resurrection, to be performed for the Easter services, but a number also dealt with the Nativity and the lives of the Prophets. Both the tropes themselves and the information about their staging have survived through the manuals of the many churches of the time.

Aside from Hrosvitha, it is worth mentioning another nun who wrote several short plays, which included a lot of music. Her name is Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). Her plays mostly dealt with the lives of saints and with the Holy Mary. Hildegard von Bingen also wrote in Latin.

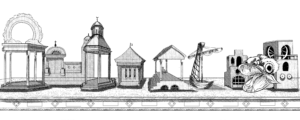

When it comes to the staging of liturgical drama, it is important to mention that it was highly stylized and relied on conventions. The performing space was divided into two parts, the “mansion” and the “platea.” The platea represented the playing space, where the performers would be, while the mansions were small structures providing visual information about the world of the play. If several locations were needed in the troupe, there would be several mansions at the back of the platea and the performers would move in front of each one according to the dramaturgical needs. This meant that all the mansions were visible for the entire time.

As we get closer to the Renaissance, stagings grew in complexity… in particular when it comes to scenery and special effects. For example, there is mention of a piece of flying machinery, which was to be used – for example – for the Annunciation.

Costume-wise, the performers used religious garments, with the occasional addition of an element to better specify the character. Women would have their heads covered and wear long robes (dalmatics).

Religious plays continued to be very popular throughout the Middle Ages, although their structure, content, and scope varied vastly. The biggest difference was the gradual shift to vernacular and away from Latin, likely to make the performances more “audience-friendly.”

Mystery (or Cycle) plays.

Mystery plays directly evolved from Liturgical Drama, as they were still based on stories of the bible and/or dramatized the lives of the saints from the New Testament. Yet, they represent the shift to vernacular drama and show a greater complexity in their structure, often extending and developing into many plays – rather than just one—, hence the term “cycle.” Most importantly, they had a “self-standing” nature, as they were not performed and staged as part of a specific ceremony, but rather as their own theatrical event (but still as part of some religious celebration and festival). Most times, mystery plays were performed outside, and at the peak of their success, they became so elaborate and intricate that they could last for several days, which implies that they were mostly produced in the spring and summer months. They spoke to the audience of their time, hence the characters had Medieval features despite being sourced from the holy books. Spectacle started to be considered necessary, and there are several records of very complex mechanisms and machinery purposely conceived and built to accommodate some form of spectacle. For example, there is detailed information about the production of a play about Noah in the city of Mons, where a complex system of barrels was conceived to “reproduce” the deluge. Violent scenes tended to be avoided (there are very few plays about the Crucifixion), but when there was action that called for a dangerous situation, actors were replaced by dummies. Some comedy slowly crept into some of the mysteries later in the 14th Century and well into the 15th Century, while still being respectful of the religious subject. In other words, there was no attempt at blasphemy but just at some comedic relief.

Dramaturgically, the plays tended to be episodic and to forego verisimilitude both in the shift between one scene and the other and in the chronology of the play timeline.

Vernacular religious drama reached its peak of popularity between 1350 and as far as 1550, and while there is a great variety of these plays that have survived and are available to us, there is little to no information about playwrights. This might also be because plays were in a sort of continuous evolution, having to adapt to the reality of their environment and production needs.

The introduction of the celebration of Corpus Christi gave way to the establishment of a Festival related to it, which became the main outlet for theatrical performances. This is often interpreted as the church’s attempt to further include the congregation in celebrating and honoring religious matters. In fact, during the Festival of the Corpus Christi, most trades were represented in the procession, while they also participated in the production of the performances. It is to be noted that during this time (between 1200 and 1350), towns and cities started to be revived and populated again, while the feudalist system somewhat lost footing. Guilds were established, thus representing the various trades of the time and giving artisans more power in negotiating their work and providing rules and standards for each craft.

France, Germany, and England produced the majority of mystery plays. In particular, it is worth mentioning that the French Play of Adam proved to be successful and generated several adaptations and productions into the 12th and 13th Centuries. This play features dialogue in French and choral songs in Latin, providing a bridge from Liturgical dramas into fully vernacular plays.

England has probably preserved the largest amount of cycle plays, starting around 1375. Most of them are grouped after the city where they were performed, which gives the name to the cycle. English cycle plays are all connected within each cycle and were conceived to be produced and performed in sequence. The known English cycles are the Chester Plays, with 24 plays; the York Plays, with 48; the Towneley (or Wakefield) Plays, with 32; and the N-Town Plays – named as such because it is unclear where they were performed— with 42 plays.

The Second Shepherd’s Play

The Second Shepherds Play is one of the most famous British mystery plays, dating around 1372 A.D.. It is part of the Wakefield cycle and is found in the HM1 manuscript, which can be found in Towneley Hall.

The play is about Nativity, but is truly a mix of contemporary Medieval elements and biblical characters.

The plot sees the three shepherds as they meet in a field to complain about a variety of things: the weather (too cold, not unusual for a British winter), their wives, the people in power, and how hungry they are. They are joined by a notorious thief, Mak, who tricks them into believing he is also quite unfortunate, as he complains about his drunk wife, who is only able to give him more children (and mouths to feed). As the shepherds fall asleep, Mak only pretends to do so, and instead he steals a sheep and brings it home to his wife, Gill. When the shepherds wake up, they realize they’ve been duped and immediately head over to Mak’s house. Gill pretends to be in labor with twins, having just given birth to one of them. She hopes this would scare the shepherds away, or at least make them not uncover the cradle where she had hidden the sheep. In the end, the ruse is revealed, and the shepherds get hold of their stolen sheep. They punish Mak by wrapping him up in a canvas and tossing him up and down until they grow tired. After all that, the Angel appears…. And the biblical story begins.

As you can see, the original part of the play heavily relies on contemporary features and is intended to be quite comedic. The play also well depicts the typical episodic nature of these works, as the whole first part is completely separate —and different in style, subject, and nature – from the second one.

Cycle plays became more and more complex, requiring long preparation and, at times, involved an ever-growing number of actors. In other words, it soon became a community effort, where religious confraternities supervised and assigned tasks and roles, but everyone had to contribute in one way or another.

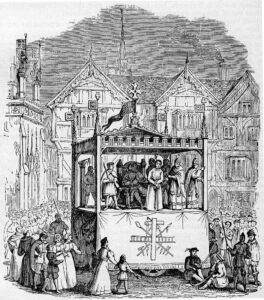

Trade guilds were involved, each one of them working on something akin to their trade. At times, a guild was in charge of producing the whole play, which would mean that they were financially responsible for all aspects of it – from providing the costumes, the scenery, the pageant wagons, and the actors. In return for their efforts, the production would become a showcase for their work, potentially bringing them more popularity and business, which would explain how soon these productions also triggered fierce competition among what we would today call producers.

Other times, the city was financially involved too.

Performance would normally have free admittance, but not always, depending on whether all the production costs had been covered.

Because of the amount of work and people that had to be coordinated, someone was appointed as the “Pageant Master”. This person would be awarded a salary and would be selected by the guild either among their members or elsewhere. The position was incredibly taxing, as it included direct supervision of all aspects of the production, from sourcing the material to building the scenery, to supervising the build itself; from finding the costumes, the actors, and attending rehearsals to make sure everyone showed up on time and had done the work: the list goes on and on. In modern times, the Pageant Master would likely be a combination of a producer, a designer, a stage manager, and a director.

Mystery and cycle plays didn’t feature huge casts; they had eight to ten characters at most. Yet, the number of performers would outnumber that, considering that those plays were performed as cycles and not individually, not to mention the number of non-speaking roles that were added for spectacle.

All actors were amateurs – there was no guild for their trade just yet! – and sourced from the local population, primarily in the lower and working classes, and in the clergy. Women were allowed to act, too, although that was not a common practice. When they were cast, the actors were asked to swear they would take the role “seriously” as they accepted the role. They had to be on time and off book (with their lines fully memorized) for rehearsals. If they didn’t abide by these rules, they would be fined. If they had to miss their work to go to rehearsals, arrangements would have to be made by the organizing guild, which would also provide libations during rehearsals. While we don’t have names to associate with those actors, it has been noted that several of them were quite passionate about doing it. The best ones were famous for their resounding voice and for their willingness to “take risks”, which at times led to dangerous situations. Actors usually were in charge of their costumes, although if they had to portray special characters (like kings, soldiers, angels, demons), either the producing guild or the pageant master would source the costumes for them. In general, though, characters would be costumed in Medieval contemporary clothing as there was no real interest in historical accuracy.

The Staging of Mystery and Cycle Plays

Scholars are very much divided when it comes to the staging of the cycle plays.

Because most of the time the plays were part of festivals, such as the above-mentioned Corpus Christi Festival, it is plausible that the pageant wagons in the procession would also serve as the location for each cycle play and the playing area, therefore providing a processional, dynamic staging of the cycle. Yet, there’s no agreement on this. Some scholars believe that while the wagons would be part of the procession, the actual performance would only start at the end of the procession. Other scholars further believe that at the end of the procession, each pageant wagon representing the background for a cycle play would travel to different locations within the town, in order to create an itinerary style of production.

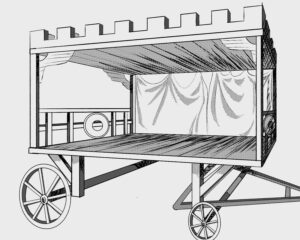

Surprisingly, there is no agreement on what pageant wagons looked like and how they functioned. Yet, there are several assumptions. Likely, they were wooden structures on wheels. Some believe they had two rooms, one on top of the other, as this would allow the actors to have a space to change and store stuff (below) and a place to perform (on the upper level). Others believe that the wagons had only one level where they would accommodate both the playing space and the old-fashioned mansions, providing a scenic background for the play.

Another kind of staging was the stationary one. In this case, all the pageant wagons needed for the production were lined up facing a platform functioning as a stage. Stationary productions took place in big courtyards, in city squares, or even in the old Roman amphitheaters. The arrangement was reminiscent of liturgical dramas, where all the mansions signifying the different locales were located side by side right in front of the playing area (the platea).

Originally, stationary stagings only featured one wagon, but then, as productions grew in complexity, the wagons multiplied. At times, they were positioned in order to reproduce the journey of the character, and other times, they would represent the two polar opposites: Heaven and Hell. In this specific circumstance, the wagons were positioned opposite each other and featured a great deal of specific decoration. For example, the wagon representing hell would look like a monster, with an open mouth, whereas the “heaven” wagon would likely carry the flying machinery. If the journey of the characters would bring them to several other locales, those would be represented by wagons lined up between heaven and hell.

We have already discussed the use of the flying machine as one of the “special effects” that were so in fashion at the time. Special effects were called “secrets” and, as such, were “guarded” by the pageant master, as the success and popularity of a production would greatly depend on them. Other secrets would be the use of smoke – which would provide an even greater devilish look and feel to the wagon representing hell, halos to signify the sanctity of characters, and the use of trapdoors.

Morality Plays

The other genre of play in vernacular is represented by the Morality Plays, which sit right at the edge between religious and secular plays. While they deal with ethical and “moral” subject matter and sometimes source their plots from the holy scriptures, they are also less faithful to the religious content. Morality plays revolve around the depiction of good versus evil and of the moral journey of the characters.

They heavily rely on allegories, which are figures of speech where an abstract idea or concept is represented by something or someone. In the case of Morality plays, characters represent concepts, such as good, evil, greed, honesty, gluttony, and so on, and the plot follows their journey as by the end they learn a moral lesson.

As you can see, Morality Plays are deeply rooted in Christianity and pursue an educational purpose. They were particularly popular in England and France, where they were staged way into the 16th Century. Like cycle plays, they featured segments in vernacular and at times (but not always) resorted to Latin for the songs.

Because Morality plays became popular in the High Middle Ages, it is quite likely that they were performed by professional actors. As for the staging, they were likely treated as cycle plays, with the same kind of wagon arrangement.

The most famous Morality play is Everyman, dating from the early 16th Century. Everyman (who represents mankind) is a sinner. He is visited by Death, who tells him that it is his time to leave this world. In despair, Everyman seeks help and company from Goods, Beauty, and Kin, but they all desert him. He turns to Good Deeds and Knowledge. When he understands that only by confessing his sins will he have a peaceful passing, Good Deeds finally consents to follow him in his final journey.

Secular Theatre

Medieval secular theatre was certainly not as popular, widespread, or organized as religious theatre, but it did exist, and will heavily contribute to the further development of comedy and physical theatre in the following centuries.

Pagan festivals had been banned by the Church, but never really disappeared, and those became the preferred performing venue for the jesters, minstrels, mimes, dancers, and the circus artists of the late Roman tradition. Those performers used popular imagery, obscene innuendos, and physical, crass comedy to please the less pious or cultivated masses. In short, secular theatre presented itself as a polar opposite to religious theatre. Where the latter would pursue virtue and morals, the former would capitalize on the vices and the weakness of mankind for comedic purposes.

Fun Fact – The Feast of Fools

Not all religious drama was exclusively serious! We have already mentioned how some elements of comedy appeared here and there as a way to engage the audience and to make the performances more in tune with the reality of the time. Yet, there were occasions where more intentionally and structurally complex comedy was introduced in religious festivals. This is the case of the early medieval Feast of Fools, a procession/festival taking place on January 1. The festival was presided over by “the bishop fool” and featured a variety of comedic episodes where the lesser clergy made fun of their superiors and of the monastic lifestyle. Jokes relied on the misuse of language, innuendos, physical comedy, and inverted hierarchy. The festival is clearly reminiscent of the late Roman pagan festivals, and while the Church did not approve of them, they survived well into the 16th Century.

Many scholars believe the roots of secular medieval comedic theatre can be found in the Feast of Fools.

At times, storytellers were a part of this mix, putting together a performance alternating music, songs, and the recounting of the life of some local (folk) hero.

Secular comedic theatre was mostly episodic in structure, with short, disconnected scenes. A through line was the fast pace that would eventually become standard in later comedies and farces. Those would feature a unified plot, like a modern one-act.

Eventually, comedies started to be penned down, and there are a few titles and playwrights’ names that have come down to us. For example, French playwright Adam de la Halle (1237- 1288) is credited with writing two comedies: The Play of Greenwood and The Play of Robin and Marion. Both plays focus on folk, pastoral tales and characters, featuring sporadic elements of supernatural nature.

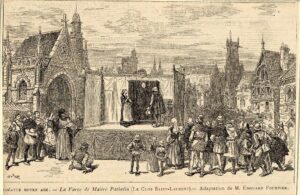

The most famous comedy/farce of this genre is probably the much later French Pierre Patelin (1470), where the protagonist is a humble, illiterate servant who ends up having the upper hand over a lawyer.

Secular theatre was particularly popular in France, Germany, and generally in northern continental Europe.

As we get closer to the 16th Century, comedic actors gained popularity and eventually formed traveling troupes.

Vocabulary

Monasteries

The Fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 A.D.)

Charlemagne

Hrosvitha

Liturgical Theatre

Hildegard von Bingen

Mansion

Platea

Mystery (Cycle) Plays

Bible/New Testament

Vernacular

Festival of the Corpus Christi

Play of Adam

Chester Plays

York Plays

Towneley (or Wakefield) Plays

N-Town Plays

The Second Shepherd’s Play

Pageant Master

Morality Plays

Everyman

Secular Theatre

The Feast of Fools

Adam de la Halle

Pierre Patelin

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

The instructor should divide the students into small groups, no more than 5 students per group.

Each group should be assigned a type of medieval theatre (Liturgical Drama, Miracle Play, Morality Play, and Mystery Play). The instructor should also provide the full text of each type of play for reference as a take-home reading.

Having read their play of reference, each group should engage in adapting a biblical story (or a saint’s story) into a short 5-minute play in the style of the type of medieval play they had been assigned. They should focus on using a similar pattern when it comes to style, language (verse/prose), and they should incorporate at least one allegorical character (Death, Faith, etc) in the story. The short play should carry a “moral” or a message.

Each group should also provide a simplified storybook focusing on the staging, which also has to resonate with the medieval staging practices.

Each group should present their play to the classroom. The presentation could be a reading or a simplified staging.

Following the presentations, a discussion could focus on both the style and the religious nature of medieval theatre and how theatricality helped (or not) strengthen it.

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 313 A.D. | Edict of Milan: Christianity Legalized by Constantine | Theater begins to decline as Christian leaders condemn it; actors and performances are associated with immorality and paganism. |

| c. 400–476 A.D. | Fall of the Western Roman Empire | The collapse of the empire leads to the end of Roman theatrical institutions; theater largely disappears until the medieval revival in liturgical drama. |

| c. 467 A.D. | Fall of the Western Roman Empire | Theater declines with the collapse of Roman institutions; it survives primarily in church rituals and festivals. |

| c. 925 A.D. | First Liturgical Drama Recorded (Regularis Concordia) | The earliest example of drama within Christian worship is performed by monks the night before Easter inside monasteries. |

| 10th–11th Centuries | Growth of Liturgical Drama | Religious dramatizations expand, using Latin and performed by clergy inside churches, illustrating Biblical stories. |

| 12th Century | Vernacular Religious Plays Emerge | Drama moves outside the church, performed in local languages, making biblical stories accessible to broader audiences. |

| 13th Century | Corpus Christi Festival Established | A major catalyst for the development of Cycle Plays, it dramatizes Biblical history from Creation to the Last Judgment. |

| 14th Century | Mystery, Miracle, and Morality Plays Flourish | Religious and moral storytelling becomes widespread; trade guilds sponsor performances in town squares. |

| c. 1376 | First Recorded Performance of a Mystery Play in England (Chester) | Marks a formalization of the mystery play tradition, performed as part of civic and religious celebrations. |

| 15th Century | Morality Plays Rise (e.g., Everyman) | Allegorical plays teach moral lessons through symbolic characters; reflect concerns with salvation and personal conduct. |

| Late 15th Century | Decline of Mystery and Miracle Plays | Social, religious, and political changes (including early Reformation sentiments) contribute to a decline in cycle plays. |

| 1517 | Start of the Protestant Reformation | Religious theater faces growing opposition; secular forms begin to rise in popularity. |

| Late 16th Century | Transition to Secular and Professional Theatre | Medieval religious drama gives way to Renaissance theater (e.g., Shakespeare); professional companies and permanent theaters emerge. |