7 Chapter Seven – The French Renaissance

Chapter 6 -The French Renaissance

Historical Introduction

The end of the 15th Century and the entire 16th Century saw France almost continuously engaged in internal turmoil and war, mostly due to the religious controversies between the Catholics and the Protestants, called Huguenots, in France. The peak of the persecution happened in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed in what is now known as the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

The situation somewhat stabilized in 1594, when the recently ascended king, Henry IV, originally a Protestant, converted to Catholicism but enforced the Edict of Nantes, which stipulated that while Catholicism was to be the state religion, Protestants were to be granted equal rights and tolerance under the law.

With new stabilized peace in the country and with the rise of even more political power and wealth coming from colonization, France colonized some regions of Canada, and the area including and around the current American state of Louisiana, the arts and literature could start flourishing again.

Another main factor in this trend was the growing exposure to Italian culture and its new aesthetic models, due to the influence of the Medici family and both Cardinal Richelieu (1586-1642) and his successor, Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661).

The Italian noblewoman Caterina de Médici had married King Henry II in 1533, establishing a strong connection between the Médici family and the House of Orléans. Three of Caterina’s sons became kings: Frances II, Charles IX (both of whom had very short reigns due to their early deaths), and Henry III, thus solidifying the Italian influence over the court and the nation.

In 1610, Louis XIII became king, but since he was still a young child, his mother, Marie de Medici, ruled in his place with the supervision of Cardinal Richelieu.

Richelieu had a strong liking for Italian culture and wanted to establish it in the French arts, particularly in literature and in the performing arts. In 1637, he promoted the establishment of the French Academy by providing it with a royal charter. The Academy was created to support the diffusion of Neoclassical ideals, along the lines of the activity pursued by Italian academies. The French Academy was formed by forty intellectuals, and it is still in existence today. Its primary role was to codify genres, styles, and the French language itself.

Richelieu’s actions were furthered by his successor, Cardinal Mazarin, who basically ruled France for a good part of Louis XIV’s reign, as this monarch as well was crowned at a very young age (he was five).

This trend will go on basically until the French Revolution of 1789.

The Early Stages

Theatre practices before the Edict of Nantes (1594) were still very rooted in a medieval aesthetic. There was a taste for forms of entertainment for the court, which often included music and dance as well as a revived interest in the Greek and Latin classics as they had been finally translated and circulated within the upper, more learned classes. A big push in the classic revival is to be attributed to a group of scholars, called La Pléiade, led by Pièrre de Ronsard. The group aimed at introducing classic principles in literature, and by extension, in theatre.

A couple of playwrights of this time applied these principles to their plays. They are Etiénne de Jodelle and Jean de la Taille. Their works attempted to conform to the Neoclassic unities, although they took some liberties. For example, the unity of space and time was not often respected.

Caterina de Médici loved entertainment, and she promoted court festivals, which revolved around a variety of sketches that included pageant shows, some singing, some dancing, and some form of spectacle.

Another form of theatre from this period was still connected to religious themes, and was closer to the Medieval aesthetics of the mysteries and morality plays… touring on wagons and mansions. Yet, over the 16th Century, the Confrérie de la Passion (instituted back in 1402) was given the monopoly to perform religious plays in Paris and in 1548 was allowed to build their theatre, the Hotel de Bourgogne, which incidentally is considered the first theatrical building ever built in continental Europe since the fall of the Roman empire.

When religious plays got banned, the Confrérie tried to come up with secular plays, but had little success. Instead, they started renting the space to other companies to make ends meet. Eventually, in 1677, the Confrérie ceased to exist.

At this point, it is important to mention Alexandre Hardy (1572-1632) as he is often referred to as France’s first professional playwright. He was quite popular during his time and extremely prolific in his writing. It is believed that he wrote hundreds of plays, although fewer than forty have survived. His works included tragedies, tragicomedies, and pastorals. He stuck to some of the Neoclassic devices, such as the use of the messenger and the chorus and the five-act structure, but he does not always respect the units of time, action, and space. He was compelled to write interesting stories, frequently using supernatural characters, and he didn’t shy away from having violent scenes happen on stage rather than off stage.

His work was likely staged at the Hotel the Bourgogne by the Royal Company, featuring some of the most well-known actors of the time, including Robert Guérin, Hugues Guéry, and Henri LeGrand.

When Hardy retired, his position as the “resident” playwright at the Hotel de Bourgogne was taken by Jean Rotrou (1609-1650), whose work focused on the dichotomy between love and honor and who was heavily inspired by Spanish drama. Yet, his plays weren’t particularly popular, in part due to the lack of psychological insight for his characters.

It was really over the 17th Century that French theatre flourished, being greatly inspired by the Neoclassical ideals and by the Italian new approach to design and theatrical architecture.

Theatrical Spaces

In 16th-century France, medieval practices in theatre were still very popular, and troupes would travel the provinces with their wagons and mansions. Italian Commedia dell’Arte troupes and French professional companies also toured extensively, performing in a variety of non-dedicated spaces that could be private halls, town halls, outdoor spaces, and tennis courts.

There were a great number of tennis courts all over Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries as the sport grew incredibly popular. Paris alone is believed to have over 250 active tennis courts within its city limits!

Because of their structure, these buildings provided an indoor space that could be easily converted into a theatrical venue. First, they were rectangular, allowing for a temporary wooden stage to be installed on one side, facing the court. Then, tennis courts already had the right disposition of seating, with up to three levels of galleries along the sides of the court, and the court itself could be used as the “pit” or parterre for the audience to stand.

Before the completion of the Hotel de Bourgogne (1548), the first public theatre, theatrical performances in Paris were held in private halls and, of course, in tennis courts. Most of the buildings that will become dedicated theatrical spaces were originally tennis courts.

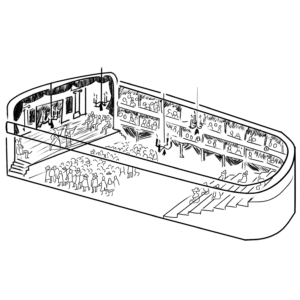

The Hotel de Bourgogne was a long, narrow building with a rectangular ground plan – quite like a tennis court! The stage occupied one end of the building and faced an empty court – the parterre, for standing audiences only. There was no proscenium arch. It has been calculated that the theatre could hold a maximum of 1600 audience members.

On the remaining three sides of the building and directly facing the court were up to three levels of galleries, some of them with boxes (loges). The upper gallery would provide somewhat of a cramped space and was ironically called paradis (heavens).

Across the parterre and opposite to the stage, there was a bench seating area arranged in an arch, looking like an amphitheater.

A tiring house backed the stage and looked similar to tiring houses in Spain and, to some extent, in England. The tiring house facilitated entrances and exits and the apparition of some scenic element of “surprise”. Yet, when it comes to design elements, there wasn’t much that helped provide a visual support for the performance, other than potentially some painted panels – there are records of the existence of some of those at the Hotel de Bourgogne — and the use of curtains. When needed to illustrate a change of location, old-fashioned (medieval style) mansions would be positioned on stage, usually stage left and right.

The Hotel de Bourgogne had a long life, hosting performances on and off until 1783, when it was briefly converted into a market, only to be demolished shortly after. It used to be in the Parisian second arrondissement, which is a very central area in Paris.

There are records of a second public theatre, the Théâtre du Marais. Originally a tennis court, it was converted into a theatre in 1634, but it burned to the ground shortly after (1643), leading to the construction of a bigger and more modern venue that could seat about 1500 people and even featured a “second stage”. The reconstruction allowed for the implementation of more modern (Italian) elements, such as the proscenium arch.

The Théâtre du Marais has later been remodeled, closed, and relocated several times over the following centuries, and today a “new” Théâtre du Marais stands and operates in Rue Volta, in the 3rd arrondissément in Paris.

In 1641, Cardinal Richelieu promoted the construction of a court theatre, specifically inspired by the new Italian style. The theatre was originally named Théâtre Cardinal and then became the Palais Royal after the Cardinal’s death. One of the first new elements that was introduced in the theatre was the proscenium arch. In addition, it featured an Italian-style scene-shifting type of machinery, which allowed for a more complex approach to the implementation of scenic design in productions. The theatre had a more “intimate” configuration and seating arrangement, with a small pit and side galleries, due to it not being open to the general public but to guests only. The most prestigious seats of the house were immediately to the side of the stage and were usually occupied by nobles.

The Palais Royal underwent a full remodel in 1646 in order to bring it up to speed with the modern technology for scene changing.

After Richelieu’s death, Cardinal Mazarin summoned to Paris a famous Italian architect and designer, Giacomo Torelli (1606-1678), to work on a second court theatre, The Petit Bourbon, which was part of the Tuiliéries Palace. This proscenium theatre became the epitome of the Italian style of theatrical architecture, featuring Torelli’s most famous devices, such as the chariot-and-pole system to shift scenes. It mostly produced ballets, operas, and “plays with machines”, such as Corneille’s Andromède, all performances that allowed a greater amount of spectacle.

The Petit Bourbon had a short life, being replaced in 1660 by the new and bigger Salle des Machines, designed by another Italian architect, Gaspare Vergani. While this newly built theatre showcased some of the best features when it comes to machinery, it had some structural flaws, including really bad acoustics. It had been conceived to be big to accommodate the celebrations following Louis XIV’s marriage, but its size also worked against it, being too big for the “regular” court entertainment.

Court theatres were popular among the nobles and the royals, who loved the implementation of the spectacle. The most popular forms of court entertainment included ballets, comedy ballets, and operas. In short, the combination of dance and music proved to be a favorite of the time. Choreography tended to be simple, which often allowed the audience, including the king himself, to participate. The most appreciated composer of the time was Jean Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), and he worked intensively on court music, at times with Molière (for comedy ballets) and later on his own.

Paris court theatres experienced a setback after 1660, when Louis XIV moved the court to the palace of Versailles, outside Paris. He forced all the nobles to move there so that he could better control their activities. As a result, most court entertainment was moved to Versailles. Yet, in 1680, Louis XIV inaugurated the Comédie Française, which is to become the very first National Theatre in existence. This theatre also resulted in a conversion from a Tennis court. This theatre would become the home of the very first resident national theatre company, which resulted in the merging of the companies originally residing at the Théâtre de Bourgogne and the Théâtre du Marais.

Theatre troupes

There were a great deal of theatre companies operating in France all throughout the 17th Century – some have estimated that number to be around 400! – yet performing in Paris required a special permission, only originally granted only to the Confrérie de la Passion, who also had exclusive access to the Hotel de Bourgogne. That ended in 1629, when another company, the Royal Company, was granted performance rights in Paris, and that space became its permanent residence.

In 1634, a second company was allowed to perform within the city limits. This company was managed by the famous actor Montdory (born Guillaume de Gilliberts) and was given sole access to the Théâtre du Marais.

Theatre troupes worked on a “share system”, similar to what happened elsewhere in Europe. The shareholders, or sociétaries, would split the profits after every performance, after taking off all of the expenses. The troupe would hire actors to fill minor roles when needed. These hired actors were called pensionnaires. Theatre troupes originally only had up to twelve shareholders, although that number increased in the later part of the 17th Century.

Theatre companies could include women! Regardless, the actors’ reputation suffered greatly due to the social and religious stigma attached to their profession.

Sociétaries were responsible for their own costumes, although the company might have some stock. Costumes were a prized possession and usually reflected the fashion of the time rather than adhering to the specific style and period of the play.

Theatre companies granted sociétaries a twenty-two-year tenure and a small pension after that, when they retired. Pensionnaires were promoted to sociétaries when someone retired or resigned.

Each company would usually have a “resident” playwright, who had the greatest say in casting the play within the troupe. Actors in the troupe could not turn down the role. It wasn’t unusual for a company to have anywhere between forty and seventy plays in their repertoire.

Rehearsals would happen daily in the morning, while performances would usually start in the early/middle of the afternoon, to allow the audience to safely go home before dark.

When it comes to performers, a few names need to be remembered, aside from the above-mentioned Montdory, who became famous for his interpretation of Corneille’s Cid.

Michel Baron (1653-1729) was one of the most respected tragic actors of the time. He was in Molière’s company and then joined the Comédie Française. He had started as a child actor, impressing Molière to the point of becoming his protégé. He is remembered for more “realistic” and less stylized performances.

Everyone in the Béjart family had a successful career in the theatre business, first in Molière’s company, which they co-founded, and later in the Comédie Française. Specifically, the two leading women in Molière’s company, Madeleine Béjart first and later Armande Béjart, became incredibly popular. Other family members include Louis Béjart, Joseph Béjart, and Genéviève Béjart.

FUN FACT

In 1641, King Louis XIII issued a royal decree attempting to minimize the social stigma attached to acting. It stated that acting was “not to be considered worthy of blame nor prejudicial to their reputation [of the actors] in society.”

The decree was somewhat helpful, but it didn’t completely resolve the issue. Actors were still marginalized, denied religious rights, and at times access to specific public places.

Genres

When it comes to genres, comedies and tragedies were equally popular, although comedies provided a greater variety in terms of style, topics, and formats.

Companies would perform either for the court (in private theatres and spaces) or for the general audience (in public playhouses, such as the Hotel de Brougogne or the Hotel du Marais), which made a huge difference in the length and style of the theatrical pieces. In particular, when it comes to comedies, as tragedies tended to have a more learned audience anyway.

Court comedies usually featured a combination of scenes, music, and ballet.

Comedies to be performed for the general audience tended to be slightly longer and rely on stock characters and other comedic devices coming from either the Classics (Plauto) or Commedia dell’Arte. They also included dance and music, as in the court comedies.

Later in the 17th Century, ballet became more popular, mostly relying on the physical storytelling of allegories. Proficiency in dance was not a requirement, and audience participation – especially at court — was highly encouraged.

Eventually, a combination of ballet, music, and theatrical dialogue started to establish what would become the French opera, particularly thanks to the work of Jean Baptiste Lully.

Playwrights

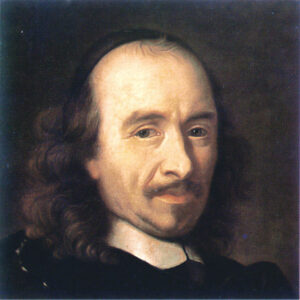

The two most important playwrights of the time, focusing on tragedies, were Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine. Their work fully embodied the new, adjusted French theatrical aesthetics, and their plays are still widely produced today all around the world.

While Corneille is remembered for the complex dynamics of his plots and for his relatively simple characters, Racine is acknowledged as focusing primarily on building strong characters, whose psychological and emotional journey drives the action.

after Charles Le Brun, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pierre Corneille (1606-1684) came from a wealthy family and became a lawyer. He started writing almost as a hobby, and he focused exclusively on comedies. His first known play is titled Mélite (1629), which was followed by many others. His plots revolved around pastorals and love affairs. Cardinal Richelieu took a liking to Corneille’s work and started commissioning his plays.

One of Corneille’s most successful plays is Le Cid, which is based on a Spanish play by Guillen de Castro and takes place in Seville (Spain). The main theme of the piece is honor versus love. The play follows Rodrigue and Chimène, who fall in love with each other but can’t be together because of a feud between their two families. After a long series of setbacks, the couple can finally marry.

While the play was a crowd pleaser, many scholars criticized its distance from the Neoclassic principles. For example, the action seemed cramped to fit the unity of time, thus losing believability, and, more importantly, it blended genres with the addition of moments of comedic relief and, of course, the happy ending. Lastly, decorum was in question too, since Chimène agreed to marry Rodrigue hours away from him killing her father.

Intrigued by the dispute, Richelieu demanded that the French Academy examine the case, and so in 1638, Jean Chapélain – the leader of the Academy – wrote The Judgement of the Academy on The Cid, where it was stated that while the play had outstanding features, it did break from the Neoclassic principles. The verdict didn’t sit well with Corneille, who stopped writing for several years out of spite. Eventually, after 1640, he started writing again, and this time he adhered strictly to the unities and mainly stuck to tragedies, including Horace, Cinna, Polyceute, and The Death of Pompey. He became a member of the French Academy and was active in it until his retirement.

Like Corneille, Jean Racine (1639-1699) was part of the French upper class. He had a very strict and religious upbringing, as he became an orphan at an early age and was raised by his grandparents and his aunt. After convent school, he studied law and became a lawyer. Yet, he was greatly interested in literature and spent most of his time in literary circles, determined to become a successful playwright. He went to great lengths to secure the support of the royals, as well as the support of anyone who could potentially be helpful. His demeanor sparked controversy among the other theatre artists, and he ended up making a lot of enemies as well.

When it comes to style, Racine truly embraced the Neoclassic aesthetic while establishing unprecedented dramatic tension and character development. All of his tragedies are based on Greek myths or plays, including his first play, La Thébaide, which was produced in 1664 by Molière. Racine’s plays include: Andromaque, Bérénice, Mithridate, Iphigénie, and Phèdre, of which Phèdre is undoubtedly his masterpiece.

Phèdre is based on Euripides’ Hippolytus and tells the story of King Théseus’ wife, Phèdre, who falls in love with her stepson Hippolytus. Being rejected by him and learning that her husband is coming back to the Palace after having been gone for several years and believed dead, she instructs her maid to spread the rumor that it was indeed Hippolytus who made an obscene advance to her. When Théseus learns this, he is enraged and asks Neptune to punish Hippolytus, who is then drowned by the god. Being ashamed of her shameful conduct, Phèdre confesses the truth to Théseus and commits suicide by drinking poison.

The five-act play perfectly showcases the Neoclassic unities, as everything happens in one day, in the same location (the palace), and it is verisimilar as the action is more contained than in Corneille’s works. Decorum is respected, too.

Last but not least, Racine’s use of language established a new standard for generations to come, with a masterful use of the alexandrine verse.

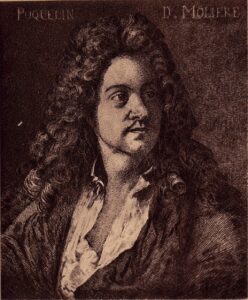

When it comes to comedies, one name tops everyone else: Molière (1622-1673).

Jean Baptiste Poquélin, later known as Molière, came from what can be considered a “middle-class” family of wealthy artisans, his father being in the furniture-making business.

He received a solid education, which would have allowed him to acquire a position in court as a lawyer, or, if he were so inclined, he could have pursued his father’s business. However, he was more interested in the arts, specifically in theatre. He was greatly influenced by the Italian Commedia dell’Arte troupes that were so popular at the time, and in 1643 he founded the Théâtre Illustre, his theatre company, teaming up with a famous family of actors of the time, the Béjarts. The company’s first successes happened in the provinces, and he only got to perform successfully in Paris in 1658 when he obtained permission to use the Petit Bourbon theatre, where his play Les Préciéuses Ridicules, a satirical take on contemporary mannerisms, became an instant success the following year.

Shortly after that, the company moved to the Palais Royal, a theatre built by Richelieu and recently remodeled after the Italian standards by Giacomo Torelli. In 1665, Théâtre Illustre was granted the title of La Troupe du Roi (The King’s Troupe) and provided with an annual financial installment.

As we have mentioned, Molière’s genius shone in comedies, and he wrote several kinds of them. His most successful ones are the so-called comedies of characters and comedies of manners. The first ones revolve around the adventures of the main character, while the second ones focus on ridiculing some aspects of his contemporary society.

To start, Molière wrote Commedia dell’Arte-inspired farces. Those were very fast-paced pieces relying on the stock characters that were made popular by the Italian troupes. Examples include The Imaginary Cuckold, where a series of misunderstandings creates chaos between a married couple and two young lovers, and The Tricks of Scapin, where the title character functions as the facilitator for the marriages between two young couples, whose parents wouldn’t want them to be together.

Molière’s court comedies were specifically written to satisfy the needs of the court for various festivities. These plays tended to be shorter and frequently featured some form of musical accompaniment, usually provided by the French rising star Jean-Baptiste Lully, Molière’s favorite collaborator. Examples of court plays include The Bores and The Forced Marriage. In other instances, the focus was on spectacle, like, for example, in Amphitryon, a comedy in three acts based on Plautus’ play by the same title. In it, King Amphitryon leaves home and his beautiful wife Alcmene to go fight a war. During his absence, the god Jupiter falls in love with Alcmène, but he only succeeds at seducing her by acquiring her real husband’s appearance. Upon the return of the real Amphitryon, confusion ensues and is only resolved when Jupiter reveals his true identity and assures Amphitryon that his wife was faithful, because she would only yield to the looks of her husband.

Great examples of comedies of character are The Miser, Tartuffe and The Misanthrope.

Molière’s ability to truthfully depict the most deplorable vices, while framing them in an extraordinarily comedic setting, is what makes a lot of his work still compelling today, although at the time, his popularity was marred with just as much controversy.

The Miser centers around the character of Harpagon, a wealthy man who wishes to marry off his daughter to an old man so that he could avoid providing her with a dowry. Yet, his daughter is in love with a young, penniless man. Harpagon himself is hoping to marry a poor young woman, who is also loved by Harpagon’s son. As you can see, the vices that Moliere exposes here are greed and stinginess. The play is resolved by Deus-Ex-Machina, like many of his plays, so that the vice itself is not resolved, but rather remediated. In this case, Anselme, the old man who was supposed to marry Harpagon’s daughter, is revealed to be the long-lost father of both the penniless young man Elise (Harpagon’s daughter) loves and the poor young woman Harpagon looked at marrying. This new information allows Elise to marry her true beau, and Cleante (Harpagon’s son) to marry Marianne (Anselme’s daughter).

Amongst all of his plays, Tartuffe is probably the one that sparked the greatest controversy when first produced. The play focuses on the duplicity and lies of the title character, a man who claims to be poor and pious to be granted access to Orgon’s house, food…. And wife. Orgon’s family tries its best to expose Tartuffe’s lies to save the family’s patrimony, but all seems lost when Orgon signs off his house in Tartuffe’s name. The play is resolved, once again, by Deus-Ex-Machina, with the intervention of the King himself, who arrests Tartuffe and re-establishes Orgon’s possessions.

Because of Tartuffe showing off his (fake) religious “piousness”, the play was not well received by the French catholic audience, who considered it insulting to their religion. Molière had to do two rewrites to get it even approved and licensed to be produced. Yet, it became popular and ran for a record of thirty-three times.

The Misanthrope’s protagonist, Alceste, is not fond of mankind in general and considers everyone to be dishonest and corrupt. He distances himself from all sorts of public displays of societal politeness, a fact that makes him very unpopular. When he finally falls in love, he finds his match in Celimène, a beautiful young woman who is a notorious flirt and actually represents everything Alceste protests about. A legal dispute ensues when Alceste insults the work of an influential nobleman. As he is summoned to court to pay a penalty, Alceste refuses to oblige, declaring that he would rather self-exile and live like a hermit, far away from “civilization”. He asks Celimène to go with him and marry him, but she refuses.

As you can see, this play has some quite serious undertones that made it not his most popular comedy at the time. Yet, as of today, it is one of his most produced plays, due to the complexity of the characters and the interesting take on society.

Moving to Molière’s comedy of manners, it is worth mentioning The Learned Ladies, in which the playwright makes fun of the newly rich, who aspire to showcase their intellectualism and appreciation of the arts, but don’t have the actual intellectual means or the education to do it.

Molière’s writing style was witty and multifaceted. He adapted it to better serve the characters and the pace of the piece, using verse and prose alike.

It is important to say that within his theatre company, he wore many hats: he was the main producer, somewhat of director, and, most importantly, he often acted in leading roles.

His life had several ups and downs, both financially and personally; he was even imprisoned for bankruptcy once. He married Armande Béjart, who was the daughter of his company’s co-founders. Armande was trained as an actor since her childhood, eventually making the first steps of what would be a stellar career within Molière’s company, where she played most of the leading young female roles. They married, but it wasn’t smooth sailing. She was much younger than he, and he was much admired, which made Molière jealous. They separated after the birth of their children, but they later reunited until his sudden death in 1673, when he collapsed on stage during a production of The Imaginary Invalid. Because actors were not allowed to have public religious rituals, his funeral was held late at night, privately.

After his death, Armande became responsible for the theatre company, along with Charles Varlet, known as LaGrange, another famous actor of the time, who later published Molière’s first biography in 1682.

TAKEAWAYS

Italian Commedia dell’Arte had a strong influence on French theatre

The Neoclassic principles played a significant role in the work of tragedist of the time.

Italian theatrical architecture and design determined the evolution of French theatrical spaces.

Corneille and Racine can be considered the epitome of dramatic writing for this period.

Molière’s comedic genius was unparalleled, and so was his popularity.

Comedies often featured a combination of dialogue, music, and dance.

Companies would perform for the court and the general audience.

Court theatre and public performances had dedicated theatrical spaces.

The monarchy – and the Church- had a lot of influence and power in determining the success or failure of a theatre company.

Theatre companies had a strong and regulated internal structure that allowed actors to have a stipend and a pension.

Women could act!

Vocabulary

Ballet

Armande Béjart

Michel Baron

Caterina de Médici

Cardinal Richelieu

Cardinal Mazarin

Comédie Française

Commedia dell’Arte

Confrérie de la Passion

Corneille

Decorum

Etienne de Jodelle

French Academy

Gaspare Vergani

Giacomo Torelli

Alexandre Hardy

Hotel the Bourgogne

Hotel du Marais

Huguenots

Jean de la Taille

Jean Rotrou

Luois XII

Louis XIII

Louix XIV

Louis XV

Jean Baptiste Lully

Molière

Montdory

Palais Royal

Petit Bourbon

Racine

Salle des Machine

Théâtre Illustre

Versailles

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

The students need to be familiar with the Neoclassical Principles (for an overview, please refer to Chapter 5).

The instructor should divide the class into small groups (4 people per group) and assign the reading of Racine’s Phaedra, so that the students would be familiar with how the Neoclassical Principles could be applied to a play.

Students should work in class on rewriting a contemporary story using the Neoclassic Principles (unity of time, space, and action, decorum, verisimilitude). Models and narratives for this exercise could include Sci-fi movies, contemporary plays, contemporary TV series, video games, novels, and short stories.

The piece should feature elevated language and “noble” characters (contemporary super-heroes qualify as noble characters).

If the plot is too complicated, it is okay to simplify it, as each group should produce a 5 to 10-minute play.

Each group should present their play to the class, either reading it or even performing it.

A discussion should follow on how easy/difficult it was to abide by the Neoclassical Principles.

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 1498-1515 | Reign of Louis XII | His rule saw growing French interest in Italian art and Renaissance humanism. |

| 1515–1547 | Reign of Francis I | Francis I invites Italian artists to France and promotes humanism and the arts, laying the groundwork for the French Renaissance. |

| 1530 | Founding of the French Academy | An institution for regulating the French language and promoting classical learning and literary form. |

| 1548 | Confrérie de la Passion loses its monopoly on religious plays | Allows secular and classical drama to flourish. |

| 1550s | Rise of Etienne de Jodelle and Jean de la Taille | Introduce classical tragedies in France; emphasize decorum and neoclassical unities. |

| Late 1500s | Caterina de Médici introduces Italian court entertainments to France | Brings Ballet and Italian staging traditions, including early influences of Commedia dell’Arte. |

| 1590s | French Wars of Religion end; persecution of Huguenots ceases | Stability returns, allowing the theater to flourish in Paris. |

| 1600s | Commedia dell’Arte troupes gain popularity | Their influence can be seen in Molière’s comic characters and improvisational techniques. |

| 1610–1643 | Reign of Louis XIII | Supported the establishment of major theaters; era of playwrights like Corneille and Hardy. |

| 1624–1642 | Cardinal Richelieu as chief minister | Promotes classical drama, founded the Académie Française, and centralized cultural institutions. |

| 1630s | Montdory and others found the Théâtre du Marais | Rival to Hôtel de Bourgogne, it launches the career of Pierre Corneille. |

| 1636 | Le Cid by Corneille | Sparks the “Querelle du Cid” and debate about decorum and classical form; pivotal in French drama. |

| 1643–1715 | Reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King | Absolute monarch who transformed French theater and built Versailles as a center of cultural life. |

| 1643–1661 | Cardinal Mazarin introduces Italian artists | Brings Gaspare Vergani and Giacomo Torelli to France, revolutionizing scenic design and machine plays. |

| 1650s–1660s | Salle des Machines constructed | A marvel of stage machinery used for elaborate court spectacles. |

| 1660s | Jean-Baptiste Lully collaborates with Molière | They create comédie-ballets, merging dance, music, and spoken word. |

| 1662 | Molière marries Armande Béjart | Solidifies connection to the Béjart theatrical family; she becomes a leading actress in his troupe. |

| 1665–1673 | Peak of Molière’s career | Writes and performs famous comedies; challenges hypocrisy and social norms. |

| 1670s | Michel Baron becomes the leading actor in Molière’s troupe | Later joined Comédie-Française, influencing future acting styles. |

| 1680 | Founding of the Comédie-Française | The first national theater: it merges several troupes, including Molière’s, and institutionalizes French classical drama. |

| Late 1600s | Works by Racine dominate tragedy during that time | Refine classical French tragedy with psychological complexity and poetic form. |

| 1715–1774 | Reign of Louis XV | Continuation of court patronage; theater becomes increasingly ornate and stylized. |