5 Chapter Five – The Italian Renaissance

Chapter 5 – The Italian Renaissance

It is fair to say that Italy became the spear carrier for most of the artistic and cultural principles of the Renaissance, particularly in Continental Europe. We will see in the following chapters on Spain and France, how much Italian artists and trends have determined the development of their national cultural identities.

In Italy, the Renaissance started early in the 14th Century for a variety of reasons. First, we can’t ignore the fact that most of the Roman artistic and archaeological patrimony was right there! The easy access to Roman artifacts and literature helped rekindle the interest in the Classics, which became a source of inspiration for new work.

At the time, Italy was divided into a multitude of small “independent” states, each one ruled by a noble family or a prince. These states had their currency, their language, and their laws, and they were quite often at war with each other. When not at war, they still had a fierce sense of competition when it came to showing off their wealth, mostly through architecture and the arts. For this reason, artists were able to more easily get patronage and financial stability through commissions, which allowed them to really explore and produce new work.

The Catholic Church still had a strong influence on the political dynamics of the Italian states: its favor could determine the rise or fall of a noble family’s fortune and power. The religious grip also heavily influenced the arts, in both its styles and subjects, so when Clement V was elected Pope in 1303 and refused to move to Rome —establishing the French Avignon Papacy, which would last until 1377— Italy experienced new artistic freedom. This created greater interest in new, more secular, artistic subjects, new forms of literature, and even the pursuit of local idioms. Nobles started to foster, support, and commission art that was more secular in its scope. Ultimately, this is one of the main triggering factors of the Italian Renaissance.

It has to be said that Latin was still very much in use within the upper classes, but the people did not have easy access to education, and therefore, each state started developing its own language, which was, of course, somewhat rooted and reminiscent of Latin. This element will prove significant in the development of theatre in its forms throughout the Italian peninsula.

Many scholars agree in considering the Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) as the artist to introduce the new artistic principles in his work, titled The Divine Comedy. While the very first form of literature written in Italian is Saint Francis of Assisi’s Canticle of the Sun (dated around the end of 1224), The Divine Comedy is considered the first complete text written in what will become the Italian language. The text is a long poem, divided into three sections – or cantiche – and represents the journey of the poet himself through the circles of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. He is accompanied by the Roman poet Virgil. During his journey, Dante will meet several notable historical characters, many of whom were his contemporaries. The piece is praised for its magnificent use of the verse, its impeccable structure, and its use of allegories. Eventually, it would become a mandatory reading for Italian students, which it still is to this very day.

Aside from Dante Alighieri, another renowned poet of the time was Petrarch (1304-1374), who studied the Greek and Roman classics extensively to reproduce the elegance of their style. Petrarch, like Dante, resided in Florence, where access to the Greek classics had been facilitated by Manuel Chrysoloras, a Byzantine diplomat who started teaching Greek to scholars and artists.

Finally, trade and commerce flourished and brought greater wealth to the notable families, which allowed stronger patronage of the arts and of artists specifically.

Later in the 15th Century, Italian scholars and artists were able to increase their exposure to the classics first through the discovery of twelve long lost plays by Plautus and later, following the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, when many scholars fleeing Constantinople (the present day Istanbul) settled in Italy, bringing along the manuscripts of the classic Greek plays and some philosophical treaties, including Aristotle’s Poetics.

Last but not least, Gutenberg’s printing press (1440) was introduced in Italy, making it possible to print and publish Roman and Greek works. It is believed that by 1518, all the Roman and Greek plays known to be in existence were published, and later even translated into Italian.

EARLY STAGES

Before the rediscovery of Greek and Roman classics, Italian early Renaissance theatre still relied on plots based on the bible and the lives of the saints, in the Medieval fashion. These theatrical events were called Sacre Rappresentazioni (Sacred Representations), and they were almost exclusively written in Latin. They were to be performed —or just read— alongside religious festivals and events.

There were also a few attempts at plays with a secular content, such as Eccerinus, a tragedy by Albertino Mussato dated 1315 and centered on the (fictional) tyrant ruler of the city of Padua. As for comedies, Pier Paolo Vergerio’s Paulus stands out. It was written in 1350 and deals with a wealthy student and his two servants.

At this stage, most playwrights attempted to mimic the style of the classics, and their works were likely meant to be read within the learned circles of the Academies rather than to be performed, meaning they were not conceived for a wide, public audience. Most plays were written in prose, not in verse.

In the 1400s, we see the rise of the Commedia Erudita, a form of comedy that will later open the door to the more popular Commedia dell’Arte. Commedia Erudita plays were inspired by Plautus and Terrence and usually had complex plots, bawdy themes, and intrigue, and featured characters who didn’t have much, or any, psychological insight. These comedies were somewhat popular, although most of them were still written in Latin and targeted a more learned and niche audience.

RENAISSANCE DRAMA IN ITALIAN

Comedies, Tragedies, Pastorals, Intermezzi, and Opera

It is only later in the 1500s, with the first plays written in Italian, that we can truly say that theatre returned to be fully available for public consumption. Most playwrights were also scholars, philosophers, and primarily wrote other forms of literature. In other words, writing plays came as a secondary skill set, which was mostly applied to please their noble benefactors. At times, plays were directly commissioned by the rulers of the Italian states to their literary protegees to complement special occasions, such as marriages, or as part of festivals.

Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533) is mostly known for his epic poem in verse, Orlando Furioso (The Frenzy of Orlando), and he is one of the first scholars and writers to consistently write in Italian. His most famous plays are La Cassaria (The Chest) and I Suppositi (The Counterfeits), which are both written in prose, while his masterpiece Lena is written in verse, following the play Negramante. Ariosto started writing plays after 1493 when he joined a theatre company in Ferrara. The company had the patronage of the duke of the town, Ercole I d’Este, who, as a theatre lover, commissioned several plays to be staged within his dukedom. It is worth mentioning that the original production of La Cassaria (1508) is also the one that first included the use of scenic design elements featuring perspective drawings.

Ariosto’s plays are worth mentioning mostly because of the novelty they represented at the time they were written and staged. He heavily dipped into Terrence and Plautus’ works, in terms of comedic devices and plots. This nowadays makes his plays feel thin, unoriginal, and closer to an exercise of style. However, Lena stands out because the protagonist -Lena- is a woman, and specifically a bawd, who is charged with facilitating two young lovers whose engagement is opposed by their families. The novelty is right there: having a woman, and a “bad woman” as the protagonist. The play has a similar plot and characters to what will become a staple in Commedia dell’Arte, where the “old characters” are portrayed as greedy and lusty over the “young characters”, whose dream of being together is supported by the ingeniousness and mischief of a servant.

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469- 1527) is a true “man of the Renaissance”, whose interests span from philosophy to politics to literature. His famous political treatise Il Principe (The Prince), published in 1532 but likely written earlier in the century, is basically an instruction manual for a new prince, with advice and guidelines about how to rule and subdue the people. We owe the term “Machiavellian” to The Prince and to the strategies Machiavelli suggested a wannabe prince should adopt to gain and maintain power. Hint: they had nothing to do with ethics and morals. The treatise is still one of the most read and quoted works on politics to this day.

More leisurely, Machiavelli wrote The Mandrake, a five-act comedy in verse. The play was written around 1518, when Machiavelli had been excluded and banned from the political life of his hometown, Florence. For some, the play is subliminally criticizing the Medici Family, who ruled Florence and chased him off. Others consider it a practical/everyday life application of the political strategies exemplified in The Prince. Regardless, the play was very popular and is still widely produced today.

Machiavelli also wrote Clizia (1525), a comedy based on Plautus’ Casina. Clizia is an orphan girl who was raised by Nicomaco. As she grows up into a beautiful young lady, she attracts the affections of both Nicomaco and his son, who scheme to marry her off to a servant who would “share” her with them. Sofronia, Nicomaco’s wife, finds out about the outrageous plot and proceeds to dismantle it with subterfuge and ingeniousness.

The first tragedy to be written and performed in Italian is believed to be either Orbecche by Giambattista Giraldi Cinthio (1504-1574) or Sofonisba by Giangiorgio Trissino (1478-1550). While Trissino modeled his play on classic Greek tragedies, Cinthio’s Orbecche echoes the Roman playwright Seneca. Cinthio was quite a prolific playwright whose style changed over the course of the years in order to gain greater popularity with the general audience. He indeed became popular, in particular when he started providing happy endings to his tragedies, allegedly transforming them into melodramas. He also wrote other forms of fiction with great success and influenced several other playwrights and writers nationally and internationally. William Shakespeare, for example, based his Othello on a novella (a short story) written by Cinthio.

Pastoral plays are referred to as the Italian Renaissance “adaptations” of the Greek satyr plays, in the sense that they seldom feature mythological characters alongside a chorus, are set in rural environments, and do not showcase on-stage violence. The plotline usually revolves around a troubled love story, and there is always a happy ending. Differently from the Greek satyr plays and other forms of comedies of the Italian Renaissance, pastoral plays were not particularly bawdy.

The most famous example of a pastoral comedy is Aminta, by Torquato Tasso (1544-1595). Aminta is a shepherd who falls in love with Sylvia, but she doesn’t love him back, despite his saving her from an evil satyr. After a series of semi-tragic events, Sylvia gives in to secure the play its happy ending.

Torquato Tasso was famous for his epic poem La Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), published in 1591, which is a fictional reconstruction of the end of the First Crusade. The poem granted him fame and success, opening the doors to some of the most important courts in Italy. Yet, his weak health and troubled state of mind worked against him. He lived a wandering life, struggling financially almost until the very end. Pope Clement VIII had resolved to provide him with a pension and to crown him Poet Laureate – a great honor- in 1594. Yet, the ceremony was deferred, and Tasso died in 1595 without receiving that title.

Intermezzi were also very popular at the end of the 1400s and all throughout the 1500s. The term literally means “in between” as they were performed between the acts of a full-length five-act play; hence, they usually came in sets of six. Initially, the six intermezzi were self-standing, but later in the 1500s, they started to be connected by a throughline.

Intermezzi heavily relied on spectacle, with a strong emphasis on special effects, costumes, music, and dance. Plot lines represented mythological allegories, which allowed little to no dialogue.

It is believed that the spectacular nature of the Intermezzi is one of the elements that facilitated the development of new devices and techniques in scenic design and construction, which will become one of the most important, if not the most important feature of the Italian Renaissance in theatre, as we will discuss later in this chapter.

The popularity of the Intermezzi eventually led to the affirmation of a new genre, the Italian Opera.

In the late 16th Century, the Florence Academy, called Camerata Fiorentina, started working on a new kind of performance that was modeled after the great Greek tragedies. This new genre was meant to harmoniously blend music and drama.

Early Italian operas were based on historical characters or events and Classic – mostly Greek — mythology. Operas featured a musical score and a libretto – the script.

Music had the upper hand in operas, with greater emphasis and importance devoted to the “arias” (solo songs), to choral parts, and duets. Most of the text was to be sung, while the spoken dialogue merely served as connecting material.

Composers achieved greater fame than the librettists, which is something that is still true today. When mentioning operas, it is common practice to just mention the composer, as in Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata (Score: Giuseppe Verdi, libretto: Francesco Maria Piave).

The very first opera on record is Dafne (1597), scored by Jacopo Peri and libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini. The play was considered almost as an experiment, and it was produced during the Carnival festivities in the Palazzo Corsi, in Florence. Unfortunately, not much of the original opera has survived, and it was later heavily reworked by composer Marco da Gagliano. Another couple of more established early operas we should mention are Euridice (1600), once again by Jacopo Peri, and Orfeo (1605) by Claudio Monteverdi.

Later, it is worth mentioning composer Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725), a representative of the Neapolitan school, who perfected the “aria” and composed a great number of operas that were performed all over the country.

In the second part of the 1600s and into the 1700s, Italian opera became very popular, prompting the construction of new, bigger, and more advanced theatres almost everywhere in the peninsula. The popularity of the new genre trespassed Italian borders as well.

In France, Jean Baptiste Lully (who was born in Italy) pursued the genre and developed it into a more complete form of performance, thanks to the addition of ballet.

In the second half of the 1700s in Austria, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart would perfect the genre and become the closest thing to a star by today’s standards. And in the following century, composers such as the German Richard Wagner and the Italian Giuseppe Verdi continued to develop and establish the popularity of opera.

Commedia Dell’Arte

The Italian Renaissance is most known for Commedia dell’Arte (literally, “Comedy of the Trade”, or “Comedy of the Professional Players”), a form of theatrical improvisation that thrived between 1550 and 1750. One of its peculiarities was that it did not exclusively target the wealthier, more educated audience; on the contrary, it really appealed to the general, less educated audience.

The origins of Commedia dell’Arte are really difficult to trace back. Some scholars believe it developed out of the mime traditions within Roman culture, while others believe it sprang out of Medieval religious theatrical practices. Regardless, Commedia dell’Arte is still one of Italy’s greatest theatrical achievements.

Commedia troupes featured up to ten performers, including women, and were often formed by family members. Troupes toured extensively throughout the country, crafting and carrying their costumes, props, and pieces of scenery.

We have mentioned how Italy was slowly developing its own national language, yet it has to be said that the affirmation of Italian as a unified language took centuries. Throughout the country, people spoke many different dialects, with each one functioning as its own language. Dante’s “Italian” was the dialect of Florence. It just happened that the most learned scholars and academies resided in or around Florence, which, as we have seen previously, led to the first educated form of theatre being written in that dialect. It is only in the 19th Century, with the formation of Italy as a unified country, that the dialect from Florence will officially become the national language.

This is important because it directly influences the development and the success of Commedia dell’Arte. Because the actors couldn’t rely on verbal communication alone (or at all), they had to be creative using narratives that were archetypical and immediately recognizable and digging deep into physical comedy and other forms of entertainment and spectacle.

Performances were heavily based on improvisation and relied on developing some fixed scenarios, with lazzi, music, and dance.

Scenarios (in Italian, canovaccio) provided the actors with an outline of the plot, establishing the characters and their dynamics. Usually, they featured a love story between two young characters, with older characters trying to undermine the lovers and a servant or a facilitator of sorts working to please one (or both) sides.

Lazzi are sequences of physical actions and gestures that enhance the comedic effect of the scene, along with its spectacle. They tend to be heavily choreographed and can be acrobatic. Each character, or group of characters, would have several lazzi they could resort to and utilize based on their specific features. For example, masters and servants would often engage in lazzi featuring beatings and a chase.

Both scenarios and lazzi have been passed on and have survived. There are several collections of them, often referred to as zibaldoni.

Commedia dell’Arte characters are divided into two main categories: the young characters and the old ones. Both of these categories are very archetypical, with no real psychological insight.

The young characters include the lovers and the servants, also called zanni.

The old characters are usually wealthy and corrupt in some way.

Because of the nature of Commedia dell’Arte, characters were often molded on the actors who played and originated them, which is why there are so many different servants.

Each character/actor developed a specific posture, physicality, and even a costume. The more unique and successful their character, the easier it would be for the audience to identify them and recruit them for further events.

Characters also reflected the geographical, cultural, and social peculiarities of the different Italian areas, cities, and countryside the Commedia troupes were originally from.

While language wasn’t the number one element in Commedia performances, actors often developed another unique idiom, which we now call grammelot, or emotional babble speech, to use in their performances. Grammelot is a totally “invented” language, with made-up words and grammar. Actors would utilize a wide range of sounds and onomatopoeias, combined with exaggerated gestures, to convey over-the-top feelings or situations. Now and then, they would “ground” the sentence with a real word to help the audience follow the storyline.

Here is a breakdown of some of the characters of Commedia dell’Arte:

Young Characters:

Zanni: Zannis are servants, and they are loud. They can have their own costume/individuality, or they can work as a group, in a way becoming somewhat of a chorus. They cause mischief and chaos, move very fast, and tend to have very complicated and acrobatic choreography. Their costume features white pants and a top with half masks. The mask is usually black with a red bump on the forehead and a crooked nose.

Arlequin – Arguably the most famous character of Commedia dell’Arte. He is a servant and is originally from the lower part of the city of Bergamo, which is the poorer part of town. He is always hungry and always looking for food. Out of desperation, he could be eating his own flesh….or poop. He is quite simple-minded and seldom pairs with another servant, Brighella. He wears pants and a jacket made of colored patches and carries a “batocio” or slapstick, a long wooden spatula originally intended to stir soup or polenta in a cauldron but here used as a weapon. He wears a half-face mask, usually black, with a red bump on the forehead – a result of previous beatings. Arlequin’s lazzi are very complex and acrobatic.

Brighella – Another servant from the Bergamo area, wittier than Arlequin and always looking for ways to socially advance himself, even if that means trying to pass for his own master. He is a trickster, as his name suggests: “briga” is Italian for “trouble”, which would make Brighella a “troublemaker.” While Arlequin has some form of ethics, Brighella would do anything to get what he wants. He sings and plays the guitar. Like all of the zannis, Brighella’s mask features the bump on the forehead, but it’s made unique by a mustache.

Capitan – This character is at times part of the zanni/young category, and at times he joins the old characters; it would depend on the scenario he is in. Some scholars believe he is the Commedia dell’Arte version of Plauto’s Miles Gloriosus. The Capitan is also called Capitan Spaventa, because he is supposed to instill immediate fear in his enemies; instead, he gets easily scared by just about anything. The Capitan is usually bragging about his heroic activity in some far-away war to impress his love interest or to obtain the favors of wealthy and older characters. Some scenarios also see him as the young lover. At times, he is called the Spaniard, as a parody of the Spanish invader, and when that happens, he uses a few “Spanish” words here and there to color his speech.

His costume has yellow and red striped pants and a matching jacket with a big and elaborate white collar. He wears a hat with a feather, and sometimes he wears a shawl. The sword is also part of the costume, although he really doesn’t use it to fight…. As every time he tries to draw it, it either breaks or won’t come out of its sheath. The Captain doesn’t always wear a mask; when he does, it is a half-face mask with a very prominent, phallic nose and/or mustaches.

Pulcinella – this is another very famous zanni, who originated in Naples. The name “Pulcinella” comes from “chicks” because his physicality recalls the way chickens walk. He has a high-pitched, squeaky voice. He is portrayed with a slightly heavier build, but he is still very agile. He has a white, almost fluffy costume, and he wears a zanni mask, with the bump on the forehead and a beaked nose.

Colombina – she is a Venetian character, a servant and Arlequin’s girlfriend. She is very clever and flirtatious, which drives Arlequin crazy. Most of the old characters have scenarios in which they have a crush on her. Several female servants are similar to Colombina, but have different names, such as Ricciolina (from her curly hair) and Smeraldina. Female characters have less extreme-looking costumes and usually don’t wear masks.

Innamorata – the ingenue, the young daughter of one of the older, usually wealthier characters. She is in love with the Innamorato, also a young character, and their love is not supported by their parents. The innamorati would have names, such as Franceschina, for example, but they would change from scenario to scenario.

Old Characters:

Tartaglia – This character originated in Genoa, and his main feature is that he stutters, usually getting endlessly stuck on a difficult word. He is more on the heavy side and wears a green costume with yellow stripes. His costume is similar to Menego’s, a character from Padua, and at times, the two characters are interchanged. Yet, while Menego is a simple-minded old servant, Tartaglia has a higher social status.

Pantalone– This character originated in Venice and is one of the most popular among old characters in Commedia. He is often portrayed opposite to the lovers and Arlequin. He is nicknamed “Il Magnifico” (the magnificent) and speaks with a heavy Venetian dialect. Pantalone is a merchant and a very greedy and lusty person. He wears red, tight pants and a red jacket underneath a black cloak. His mask is black with a long, crooked nose. He often carries a leather pouch full of money attached to his belt.

Dottore (also known as Balanzone) – The Doctor comes from Bologna; he is a heavy old man with a prominent belly. He is as smart as a doctor should be. As Bologna was the first Italian town to have a university, this mask likely originated because of that. The Doctor often resorts to speaking “latinorum” – made-up Latin — or complex language to impress people, only to reveal his ultimate ignorance. He loves food. He wears black pants and a black jacket with a white ruffled collar underneath a black cape. His mask is unique: it covers his forehead, featuring bushy eyebrows, and has a very large, round nose, but it doesn’t cover the cheeks.

Gianduja – This character originated in Torino, and his name comes from a kind of chocolate that is typical of the area: the “gianduiotto” is a well-known truffle from Torino, still today. Gianduja is a jolly old man with a heavy build and an inclination for wine, food, and…. Beautiful ladies (who are usually younger than he). He has a girlfriend, Giacometta, who is quite jealous because of his flirtatious behavior.

When it comes to popularity, Commedia dell’Arte troupes really achieved it, and they traveled extensively because of the high demand coming from the audiences.

One of the most famous troupes was I Gelosi (The Zealous Ones), which was active at the end of the 16th century and into the beginning of the 17th Century. The company manager was Francesco Andreini (1548-1624), who started off playing the young lover (Innamorato) and, as he aged, moved into the role of the Captain. His young wife, Isabella Andreini (née Canalis), played the Innamorata opposite Francesco and then Colombina, and later became one of the most appreciated actresses of her time, along with being a scholar who wrote sonnets and poetry. I Gelosi toured France for several years and got to perform for King Charles IX as well. It has been said that they were an inspiration for Molière.

Other known troupes were I Confidenti (The Confidents), I Fedeli (The Loyal Ones), and I Desiosi (The Desired Ones). This last troupe, in particular, was directed by a woman, Diana da Ponti, and was active in the second half of the 16th Century. I Desiosi is remembered for actor Tristano Martinelli, who portrayed a remarkable Arlequin.

Commedia dell’Arte troupes usually performed outdoors or in non-dedicated theatrical spaces.

Commedia Dell’Arte Today

Commedia Dell’Arte is still taught in theatre schools all around the world, and it is an integral element in the training of actors in most conservatories.

The Italian Piccolo Teatro of Milano (now Strehler Theatre) has probably the longest-standing tradition of teaching and performing Commedia dell’Arte characters, most notably the character of Arlequin. Italian director Giorgio Strehler (1921-1997) worked on a production of Arlequin first with actor Marcello Moretti in 1947 and later in 1959 with actor Ferruccio Soleri (born 1929). The production has been revived several times, and it is touring to this very day. Ferruccio Soleri performed in it until 2018 (he was 89), when the role was taken over by Enrico Bonavera.

Other reputable institutions teaching Commedia are the Accademia dell’Arte in Arezzo (Italy), the Scuola Internazionale dell’Attore Comico in Reggio Emilia (Italy), directed by Antonio Fava, and The Commedia School in Copenhagen (NL), where training combines Commedia dell’Arte with Jacques Lecoq.

In the USA, the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre in Blue Lake, California, is an important reference for training in Commedia.

The Neoclassical Idea in Theatre

Renaissance literature, architecture, and theatre are deeply influenced by the so-called Neoclassical Ideal, which is a concept that started to develop in the second half of the 16th Century after the rediscovery of classic texts. For theatre specifically, the most influential sources were Aristotle’s Poetics and Horace’s Art of Poetry for dramatic criticism and Vitruvius’ De Architectura (On Architecture) for the development of theatre buildings and scenery. These texts had been translated and made available after 1549.

The three scholars who can be considered responsible for the definition and implementation of the Neoclassical Ideal are Antonio Minturno (1500-1571), a Catholic bishop, Julius Caesar Scaliger (nee Giulio Bordon, 1484-1558), a philosopher and a physician and Lodovico Castelvetro (1505-1571), a scholar and the greatest advocate of Aristotle’s philosophy in Italy at the time.

The Neoclassical Ideals deeply influenced playwrights and scholars, particularly when it comes to the upper classes and the more elevated styles of drama.

What does the Neoclassic Ideal entail in theatre?

First off, following Aristotle’s principles, there were to be only two genres: comedy and tragedy. Ideally, to have a “good” play, there shouldn’t be any crossovers between the two genres. In other words, tragedies could not have a happy ending but must culminate in some sort of catastrophe.

Tragedy was considered the best genre out of the two, because it dealt with ideals and a higher scope, which was also educational for the audience. Tragedies needed to deal with historical matters or mythological stories, feature characters of higher social status, and be written in elevated language (poetry). All forms of violence need to happen off stage and be reported.

Comedies had to be about common people and common matters; they were written in prose and needed to have a happy ending.

According to the Neoclassical Ideal, theatre was supposed to teach and please – which is a concept that comes straight out of Horace’s Art of Poetry. This is a different approach from Aristotle, who believed that theatre (and tragedy specifically) should only teach and have nothing to do with “pleasing” the audience. Spectacle was certainly something that needed to be in a play, but according to Aristotle, its function was to draw the audience’s attention rather than to simply entertain them. Horace, on the other hand, believed that there is educational value in pure entertainment, as the audience tends to learn something by opposition or by experiencing it from a different perspective. So, for the neoclassic scholars, comedies had educational value as they showed how ridiculous behavior could lead to bad choices, while in tragedies, the outcomes of tragic mistakes tended to be self-explanatory.

Two key concepts of the Neoclassical Ideal are decorum and verisimilitude.

The principle of decorum stated that characters needed to behave appropriately, according to their given circumstances (social status, age, profession, sex, etc.).

Verisimilitude pleaded that theatre needed to be as “close to life” as possible, although our contemporary concept of “close to life” is quite different from that ideal.

In order to be “close to life,” a play needed to deal with matters that were of this world and include realistic situations and characters. In other words, supernatural elements or fantastic characters were to be avoided (unless they were of mythological or religious nature). Soliloquies were to be avoided, as it is unnatural for a person to speak their thoughts in the presence of nobody.

The play also needed to respect the three unities: the unity of time, of space, and action.

The unity of time requires that the action in a play needs to unfold, develop, and resolve in a reasonable time, because the audience would be attending the production for a limited amount of time, and they wouldn’t believe the character’s journey if it spanned too long a period. It was agreed that all the action in the play should develop within twenty-four hours.

The unity of space wants the main action to occur in the same place: the same building, the same room, the same city, the same geographical area. Once again, this was justified by the fact that it wouldn’t be believable for the action to happen in several places within the time restriction: characters wouldn’t believably have the time to move from one place to the other.

The unity of action wants the play to focus on one main plot element, involving a set (and usually small) number of characters. This would translate into having no subplots, which were otherwise particularly popular, for example, in Shakespeare’s works.

While the three unities were supposed to come from Aristotle, it has to be said that the Greek philosopher was never particularly strict on them, contrary to what would become the Neoclassical Ideal.

Finally, the Neoclassic Ideal wanted plays to use reality, story lines, and plots to disclose more universal and moral teachings, in terms of justice or religion.

Scenic Design

When it comes to design, it was considered important to provide information about space and time and to have characters dressed appropriately (according to decorum), yet that didn’t translate to what we would consider a realistic approach to set or costumes. Design had to be suggestive, rather than naturalistic.

Scenic Design and the introduction of perspective.

Some of the greatest Italian theatrical achievements of the Renaissance pertain to scenic design and theatre architecture. The most influential works that document the Italian architectural and scenic “revolution” are: the re-discovered De Architectura, by the Roman architect Vitruvius, Sebastiano Serlio’s Architectura (1545), Nicola Sabbatini’s Manual for Constructing Theatrical Scenes and Machines (1638), Guido Ubaldi’s Six Books of Perspective (1600) and Fabrizio Carini Motta’s Construction of Theatres and Theatrical Machinery (1668).

In 1486, Vitruvius’ De Architectura was published, and by 1521 it was translated into Italian, making its circulation among Italian artists and architects much easier. Vitruvius devoted an entire section of his treatises to theatrical buildings and sets, and while he did not provide any kind of drawings, he wrote detailed descriptions. The Roman Academy and several architects attempted to reconstruct the ideal Roman theatre by coming up with illustrations and models for those descriptions. The most successful at it was certainly architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554), whose drawings for Vitruvius’ comic, tragic, and satiric scenes became the go-to illustration for their construction. For the tragic scene, Serlio envisioned a street with monumental, stately buildings; for the comedic scene, he drew a street with popular, common buildings, and for the satirical scene, he provided a pastoral, countryside setting.

In his drawings, Serlio imagines the theatre being enclosed in a rectangular room, with the stage occupying the shorter side. The performing area was flat, quite narrow, and positioned far downstage, close to the audience. Behind it, the floor pitched upwards significantly till it met the upstage wall, to provide the illusion of distance. On the side of the raked portion of the stage, there would be four sets of painted wings, the first three of which would be positioned at an angle, while the last one would be flat. Finally, the back wall had a painted backdrop. The painted wings and the sloped stage would follow the newly perfected rules of perspective, providing an illusion of depth and distance.

This arrangement of scenic elements was certainly a novelty and provided a much-appreciated improvement in scenic design. Yet, it was (intentionally) made very difficult, if not impossible, to accommodate scene changes, which is the issue that later architects and artists attempted to solve.

Nicola Sabbatini provided two options in his Manual for Constructing Theatrical Scenes and Machines. Alternate sets of wings could either be maneuvered in, upstaging the previous ones, or the existing wings could be covered with painted canvas. The backdrop would be painted on two panels, which could slide left and right off stage to reveal a new one.

Later, and with better knowledge of perspective, it became possible to substitute the angled wings with flat ones, allowing alternate sets of wings to be positioned directly behind the original ones, thus making scene changes much easier: the visible set of wings could just slide off stage. This system is often deemed “the groove system.”

The first recorded use of this method is credited to architect Giovan Battista Aleotti (1546-1636) in 1606, who designed the Teatro Farnese in Parma, the first theatre to introduce the proscenium arch.

Most of the perfected technique of painting flat wings to create a perspective picture is to be found in Guido Ubaldi’s Six Books of Perspective.

The ultimate solution for seamless scene changes will be achieved by Giacomo Torelli, also known as “the wizard” (1608-1678), who invented the famous “chariot-and-pole” system and installed it for the first time in the Teatro Novissimo in Venice around 1641.

The system featured the painted flats being mounted on poles, which would pass through the stage to be secured on small two-wheeled wagons below the stage. The wagons would move sideways on tracks operated by a complex series of pulleys, ropes, and winches. All of the wagons could be moved simultaneously, allowing all the visible flats to slide off stage, either revealing the new sets of painted wings behind them or having new sets also being wheeled in in the same fashion.

The pole-and-chariot system immediately became the number one solution for scene changes, and Torelli was often commissioned to install it in theatres all over Europe.

Fabrizio Carini Motta, who was an architect and the technical director of all theatrical activities in Mantua (Italy), later published Construction of Theatres and Theatrical Machinery, which includes the most accurate description and illustration of the pole-and-chariot system. His manual was widely utilized all across Europe during the Renaissance.

Unfortunately, today, there are very few theatres from that period that still have a functional pole-and-chariot system. The oldest one is the Ekhof Theatre in Gotha (Germany), then we have Drottningholm Theatre in Stockholm (Sweden), and another one is in the small Czech town of Český Krumlov (more about this theatre in Chapter 9).

Theatrical Spaces

Throughout the 16th Century, many performances would still take place in outdoor spaces, such as gardens or courtyards. On the other hand, indoor performances would become more and more popular, usually taking place in big banquet halls and ballrooms, and then the innovations in scenic design and the research on classic architecture led to the design and construction of theatres that would respond and accommodate the new aesthetic and theatrical vision.

As mentioned previously in this chapter, Serlio’s Architectura discussed theatre architecture and provided illustrations of what a theatre should look like. His drawings visually translated what Roman architect Vitruvius had described in his De Architectura while at the same time incorporated the new principles of perspective, taking inspiration from the sketches and drawings by a fellow architect and theatre artist, Baldassarre Peruzzi (1481-1536), who is credited to be the first to introduce the concept of perspective in painted theatrical scenery.

There was mention of a newly constructed theatre within the Uffizi Palace in Florence, dating 1586, named the Medici Theatre and designed by the famous architect Buontalenti. The theatre featured a sloped floor, which allowed the audience to have a better view regardless of how close they were to the stage, and there is mention of it having a proscenium arch, which would be the first one in history. The Medici Theatre had a short life, though, due to more theatres opening in town. It briefly served as the seat of the Senate when Florence became the capital of Italy (1865-1870), and after that, the whole building was remodeled, leaving only the entrance to the theatre in its original form.

The oldest and most famous theatre of the Italian Renaissance is the Olympic Theatre in Vicenza, which was built between 1580 and 1584 by the Olympic Academy of Vincenza with the intent of creating a model of the “perfect” classic theatre.

The theatre was enclosed in a pre-existing, quite plain medieval building that had originally functioned as a prison and as ammunition storage. Since the building had been abandoned, the municipality of Vicenza allowed the Olympic Academy to use it for the construction of the theatre, which was inaugurated in 1585 with a production of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, and then, it was later used for classic stagings and recitals.

The Olympic theatre of Vicenza was originally designed to look like a Roman Odeon by Andrea Palladio (1518-1580), who unfortunately died before seeing it completed. Palladio gained notoriety within the Olympic Academy of Vicenza through his previous designs for classically inspired villas and for providing original illustrations to Daniele Barbaro’s Italian translation of Vitruvius’ De Architectura. When he died, the supervision over the building construction, along with the design and the build of the scenery, passed to Vincenzo Scamozzi (1552-1616).

The theatre features a semi-elliptical wooden seating area that surrounds a small semi-circular orchestra. The raised stage is rectangular, with a somewhat narrow downstage playing area backed by a monumental stone façade. There are five openings in the façade, three directly facing the audience and two side ones. The façade is very ornate, with three ordered columns, niches, and statues.

Scamozzi’s wooden painted scenery is positioned at the sides of the openings in the façade according to the laws of perspective, so that it could provide the illusion of depth and distance. The scenery represents the streets of Thebes.

The seating area is topped by two tiers of gallery, punctuated by columns and more niches with statues. The ceiling above the seating area is painted to represent the sky, while the space directly above the orchestra and the stage has a more complex pattern design.

Palladio mentioned using the archeological remains of the Roman Berga Theatre as an inspiration for the design of the Olympic Theatre.

The theatre has survived two world wars and still stands today, perfectly preserved. It is also still being used for recitals and award ceremonies.

The success of the Olympic Theatre in Vicenza prompted the commission of another theatre for the duke of Mantua and the Academia dei Confidenti. The theatre in question was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi and built in 1588 in Sabbioneta. It was smaller and simpler than the one in Vicenza and was intended to stage productions of comedies, which translated into a less monumental and ornate approach to the scenery.

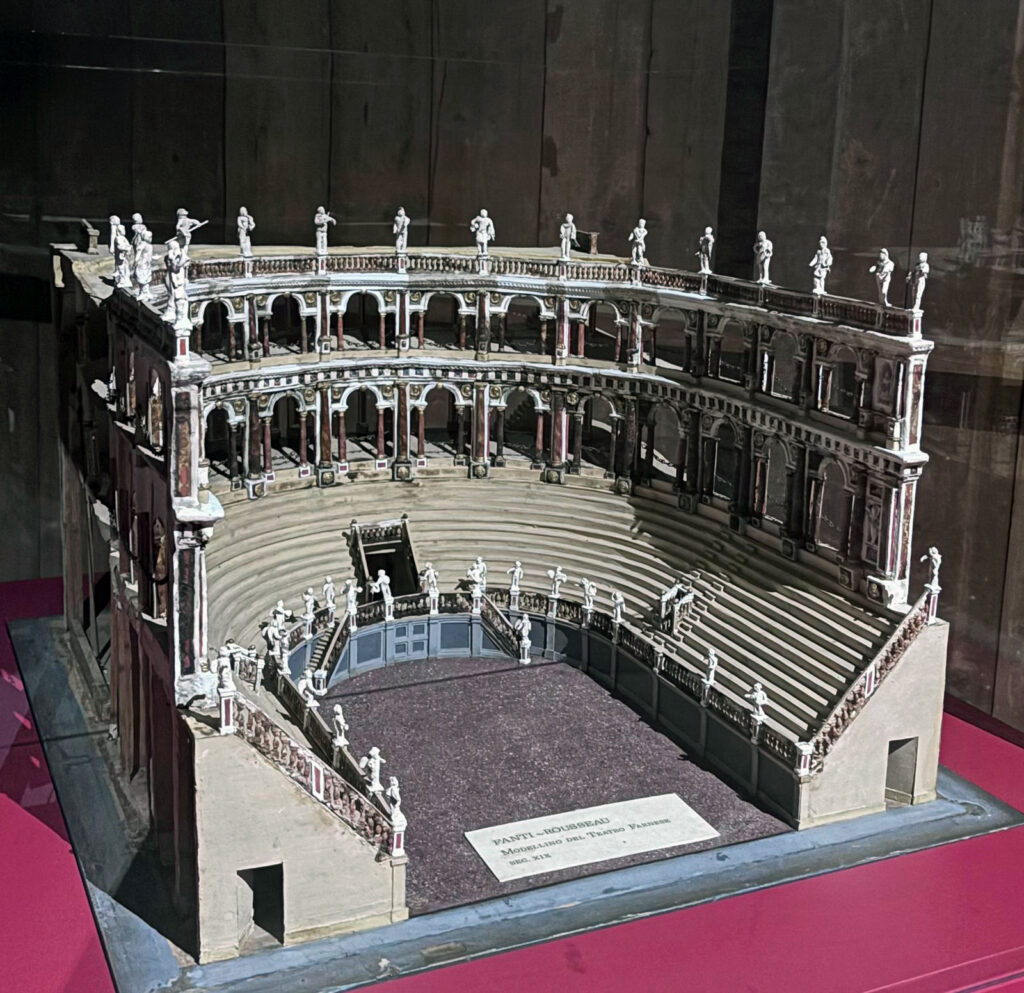

Another theatre that must be mentioned is the Teatro Farnese, in Parma, which was completed in 1618 and is the oldest surviving theatre featuring a permanent proscenium arch. The proscenium arch will become a standard feature of most theatres in the 17th Century, because it allows to “frame” the stage in a way that, combined with a careful arrangements of flat wings, allows to cover the audience’s site lines, hiding all the technical elements that would interfere with the “magic” of the production happening on stage.

The Farnese Theatre was designed by Giovan Battista Aleotti (1546-1636) and it was enclosed in the Great Hall of the Palazzo della Pilotta, which was the home of the Duke of Parma, Ranuccio I Farnese. Aleotti took inspiration from the other two existing theatres: the Olympic Theatre and the Teatro all’Antica in Sabbioneta.

Surprisingly, it didn’t get used much in the first ten years of its existence, as it was inaugurated only in 1628 for the wedding of the Duke’s son, Odoardo, with Margherita de Medici.

The theatre has the usual horseshoe seating configuration surrounding the orchestra. It has been determined that the theatre could seat 3,500 people. The entire building is in wood, although the decorations and the architectural details – including the two orders of semi-columns— are covered in thick and levigated stucco to provide the illusion of marble.

The theatre was badly damaged during the Second World War, but a 1962 careful and patient reconstruction based on the original drawings has returned it to its original appearance, making it a popular tourist attraction in the city of Parma. While it is not used for theatrical performances any longer, it still occasionally hosts concerts and recitals.

The Olympic Theatre, the Teatro all’Antica di Sabbioneta, and the Farnese Theatre were all private theatres: they were not used for public performances. Moreover, they were almost exclusively used to stage classically inspired plays – either tragedies or comedies.

In other words, the regular theatre goer would not have been able to “buy a ticket” to attend a performance in any of those three theatres. Instead, the general audience would attend less ornate and elaborate public theatres, which started to be built all around Italy more or less at the same time. Those venues would mostly produce operas.

These theatres borrowed some of the characteristics of the Farnese Theatre, mainly concerning the stage, the off-stage area, and the proscenium arch, but they developed a new and more structured space for the audience. The drawings for the Venetian SS. Giovanni and Paolo Theatre show the area surrounding the pit being divided into five tiers of balconies, featuring twenty-nine boxes each. The cost of the ticket would decrease from the lower to the upper tier. Boxes became popular because they could accommodate families and small groups of people. The pit area was the overall cheapest and could accommodate standing audience members. The S.S. Giovanni and Paolo Theatre was built in 1639 and had a very short life, as it was closed in 1715 and then demolished in 1748.

As theatrical performances moved more permanently into indoor spaces, lighting acquired greater importance. For the most part, theatres used oil lamps and candles for both the auditorium area and the stage. Candles were preferred, as they carried less smell and produced less smoke. They were usually mounted on chandeliers and wall sconces in the auditorium.

The stage was lit by footlights, placed downstage close to the edge of the stage, and masked by a small parapet. Oil lamps were also hung above the stage and mounted on poles, to be concealed by masking pieces. Rudimentary ways to increase the light and to give it some direction included placing a reflecting surface directly behind the light source. For light changes or blackouts, the lamps could be extinguished altogether– which was the most effective way to obtain a black out, although this method made it quite difficult to go back to a lit scene – or a metal cylinder could be lowered to conceal the flame, or – if the lamps were mounted on poles – the pole could rotate upstage.

Clearly, the use of live flames in theatres could have dreadful consequences; several fires broke out and damaged the theatres, at times, quite severely.

When it comes to scenic design, opera houses made great use of painted panels mounted on tracks that would slide in from the wings. Otherwise, the panels could be rigged above the stage to be lowered and lifted up when needed. Painted canvases were also popular. These could also be rigged above the stage and made to collapse with a series of ropes and pulleys. Last but not least, the use of trap doors allowed for a sudden apparition/disappearance of a character.

If the production required sound effects, the off-stage crew had to get creative and find ways to reproduce a sound live, utilizing whatever was available. Basically, they achieved what much later was called the Foley Table. For example, in order to reproduce the sound of thunder, big stones would be run inside a metal channel.

TAKEAWAYS

The Renaissance started way earlier in Italy than in other European countries.

The rediscovery of Classic material led Academies and scholars to try to emulate the Greek and Roman style in plays (tragedies and comedies) and architecture.

The Neoclassic Ideal heavily influenced the writing of plays.

Theatrical performances included tragedies, comedies, pastoral plays, and intermezzi.

Opera started to gain popularity.

Theatres were built according to the classic ideals. The Olympic Theatre in Vicenza, the Teatro all’Antica in Sabbioneta, and the Farnese Theatre in Parma are the only three theatres of the Italian Renaissance still in existence and still functioning.

The use of perspective provided a new approach to scenic design, while mechanisms to rapidly change scenery were developed and implemented in Italy and beyond.

The proscenium arch is introduced – the oldest one still in existence being in the Farnese Theatre.

Commedia dell’Arte troupes became very popular and traveled extensively throughout Italy and beyond.

Vocabulary

Dante Alighieri

Divine Comedy

Manuel Chrysolares

Petrarch

Fall of the Byzantine Empire

Sacre Rappresentazioni

Commedia Erudita

Commedia dell’Arte

Pastorals

Intermezzi

Opera

Ludovico Ariosto

Lena

Niccolo’ Macchiavelli

The Mandrake

The Prince

Giambattista Cinthio

Giangiorgio Trissino

Torquato Tasso

Aminta

Alessandro Scarlatti

Jacopo Peri

Dafne

Claudio Monteverdi

Scenarios

Lazzi

Slapstick

Zibaldoni

Characters of Commedia dell’Arte

Zanni

Grammelot

I Gelosi

Isabella Andreini

Neoclassical Ideal

Decorum

Verisimilitude

Unities of time, space and action

Vitruvius

Sebastiano Serlio

Perspective

Giacomo Torelli

The chariot-and-pole system

The groove system

Giovan Battista Aleotti

Olympic Theatre – Vicenza

Teatro all’Antica – Sabbioneta

Farnese Theatre -Parma

Baldassarre Peruzzi,

Andrea Palladio

Vincenzo Scamozzi

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

Let’s write a lazzo!

The instructor should divide the class into small groups – no more than 4 students per group.

Students should be familiar with the characters/masks of Commedia dell’Arte and with the concept of grammelot (emotional babble speech).

Students should work in class on devising a 3-minute scene (lazzo). The scene should have a clear beginning, a development, and an end, and it should feature at least one of the old Commedia characters and one of the young ones. Students should come up with a situation and a basic plot, and then they should improvise the scene.

First, they should use modern-day English. When they have the dialogue down, they should “translate” it into grammelot, making sure to ground it with a few English words here and there to make it easier to follow the story.

The students should focus on the themes of Commedia and on the nature of the characters, rather than on the specific physical qualities of each character.

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 1308–1321 | Dante Alighieri wrote The Divine Comedy | Landmark literary work that blends Christian theology with classical influence; marks the beginning of Renaissance humanism. |

| 1304–1374 | Life of Petrarch | Considered the “Father of Humanism,” his revival of classical texts laid the foundation for Renaissance culture. |

| 1397 | Manuel Chrysoloras begins teaching Greek in Florence | Reintroduces Greek literature and philosophy to Western Europe, spurring Renaissance humanism. |

| 1453 | Fall of the Byzantine Empire | Greek scholars flee to Italy, bringing classical knowledge that fuels the Renaissance. |

| Late 1400s–1500s | Sacre Rappresentazioni flourish | Religious drama was performed in vernacular Italian, precursors to secular drama. |

| 1518 | Niccolò Machiavelli wrote The Mandrake (La Mandragola) | Satirical Commedia Erudita that critiques corruption; an example of secular humanist theater. |

| 1520s | Machiavelli’s The Prince circulates | A political treatise that defines pragmatic rule; it influences themes of power and politics in Renaissance drama. |

| 1531 | Ludovico Ariosto writes Lena | An important example of Commedia Erudita, using classical models and contemporary Florentine dialect. |

| 1550s–1600s | Rise of Pastoral Drama | Idealized rural settings and mythological themes; precursor to opera. |

| 1580 | Torquato Tasso wrote Aminta | A landmark pastoral play blending poetry and music. |

| 1550–1600s | Popularity of Intermezzi | Lavish, allegorical performances between acts of plays; merge music, dance, and visual spectacle. |

| 1580s–1700s | Development of Opera | The first operas combine music and drama; Jacopo Peri composed Dafne (1598), considered the first opera. |

| 1607 | Claudio Monteverdi composed Orfeo | Establishes opera as a major art form. |

| 1500s–1700s | Growth of Commedia dell’Arte | Improvised popular theater using stock characters like Zanni; performed lazzi, physical comedy, and grammelot; supported by Zibaldoni (notebooks of scenarios). |

| 1568 | I Gelosi commedia troupe was founded. | Famous traveling company; includes actress Isabella Andreini, who becomes an icon of female theatrical skill. |

| 1500s | Rise of the Neoclassical Ideal | Based on Aristotle and Horace, emphasized decorum, verisimilitude, and unities of time, space, and action. |

| 1st century B.C. (rediscovered c. 1486) | Vitruvius’ De Architectura was published | Treatise inspires Renaissance stage design and theater architecture. |

| 1440 | Gutenberg’s printing press was introduced in Italy | Roman and Greek works began to be published, and could circulate in the country. |

| 1537 | Sebastiano Serlio publishes Architectura | According to the date listed, Serlio’s work focused on five architectural orders |

| 1600s | Giacomo Torelli invents the chariot-and-pole system | Transforms scenic shifts; supports spectacle in opera and intermezzi. |