2 Chapter Two – The Romans

Caterina Mordeglia

Chapter 2 -The Romans

The Roman drama: origins, developments, theatrical organization

As with the Greeks, the origin of theater for the Romans was linked to religious practices. The Latin historian Livy (Titus Livius) in his Annales (7.2.1-7) tells us that in 365 B.C. the Romans instituted ‘scenic games’ (ludi scaenici) to appease the gods so that they would put an end to a violent plague that had been vexing the city for some time. The Romans, therefore, brought in dancers from nearby Etruria, an Italic civilization that at that time was more culturally advanced than the Roman one, to dance to the sound of the flute. Gradually, dialogue and songs (Fescennini) began to be added to the music and dance, first in unconnected and improvised scenes to be performed by young Romans (saturae) and then gradually written with a full plot (fabulae) and performed by professional actors. This evolution really pleased the audience of the time.

The earliest evidence of such a performance, always according to Livy, is poet Livy Andronicus’ verse Latin translation of Homer’s Odyssey in 240 B.C. This work represents a turning point in the history of Roman theater. In fact, the performance blends different international and intercultural influences: the original Etruscan one and the Greek one, as the Romans had learned about Greek culture as they expanded their empire in the south of Italy. This new style of performance becomes entirely original for the choice of the subject matter, its setting, and its technicality.

Over time, different stage practices and performances developed, inspired by either the Italic and Roman traditions and/or by the Greek tradition, and sometimes being a combination of the two different influences, and they can be grouped as follows:

- The fabula palliata: a Latin comedy with Greek subject matter and setting. This genre is modeled after the so-called ‘new’ Greek comedy championed by Menander and other Greek comic poets of the 4th-3rd centuries BC. The name “fabula palliata” comes from “pallium”, which is the classic Greek word for cloak.

- The fabula togata: a Latin comedy with an original subject matter and set in Rome. It takes its name from the toga, the traditional Roman dress. This genre of performance had a very short and unsuccessful life.

- The fabula cothurnata: a Latin tragedy with Greek subject matter and setting, that is modeled after the Greek tragic poets of the 5th Century B.C., such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. It is named after the “cothurni”, the platform shoes worn by classic Greek actors when they performed tragedies.

- The fabula praetexta: a Latin tragedy of Roman subject and setting. Named after the ornate purple dress worn by all freeborn Roman youths.

- The fabula Atellana: a performance of a comic and farcical nature, probably shorter than a regular comedy. It featured a written plot that actors could improvise from and included stock characters. This kind of comedy can be compared to the later Italian Commedia dell’Arte. It is named after the town of Atella, in the current Italian southern state of Basilicata. The Fabula Atellana truly represents the Italic style in all of its features and will eventually greatly influence Roman comedy.

- Mime: a performance of popular and improvised nature, that arrived in Rome from Magna Graecia and Sicily during the 3rd Century B.C, after having originated in the 5th Century B.C. It eventually gets to be scripted, featuring stereotypical plots and characters similar to those found in comedy. After 73 B.C., mime was included in theater festivals and became very popular throughout imperial Rome. Much of its success is because it is the only kind of performance that allowed women to participate in, although their role often almost exclusively featured undressing (nudatio mimarum) and bawdy acts.

- Pantomime, this form of performance, is the forerunner of modern dance. It is mainly based on mythological and classic tragic subject matter. The actor, silent and wearing a mask, performs through movement alone the story as it is told by the chorus to the accompaniment of music, impersonating both male and female characters with his dance. The actor may also be joined by an ensemble of female dancers. This style of performance was introduced in Rome in 22 B.C. by Pilades of Cilicia and Batillus of Alexandria, and it became a staple form of entertainment of the imperial age, with great success. Pantomime was also performed in between the acts of a tragedy.

- Circus games: they are enormously successful, especially during the imperial age, when, together with mime and pantomime, they effectively supplanted traditional theater. They included gladiator combats, fights with feral animals (venationes), reproductions of naval battles (naumachiae), chariot races, and athletic contests.

As was the case in the Greek world, all plays and theatrical performances took place during the day as part of multi-day festivals that were produced by public officials and paid with public money. The following are the most important Roman festivals:

- Ludi Romani: since 367 B.C., this festival took place annually in mid-September in the Circus Maximus and was organized in honor of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. Because of their incredible popularity, they went from being three days long to a full nine days. They included athletic activities such as running contests, boxing, wrestling, and horse racing. In 364 B.C., they started including theatrical performances. Gladiator combats were added starting in 264 B.C.. The first Latin tragedy was staged in 240 B.C.; it was Livy Andronicus’ Odusia.

- Ludi Plebeii: this festival was dedicated to Jupiter and happened in mid-November in the Circus Flaminius. It initially only included sports, but later it hosted theatrical performances as well. During the imperial time this festival could last up to 14 days.

- Ludi Apollinares: this festival was held in July and was dedicated to Apollo. It was established in 212 B.C. and began to host theatrical performances starting the year 199 B.C. It originally took place in the Circus Maximus.

- Ludi Megalenses: this festival was established in 204 B.C. as a tribute to the goddess Cybele, also known as Magna Mater. Her cult was strong in Asia Minor and was later introduced in Rome. Theatrical performances were added to the festival in 194 B.C. and took place annually in April.

- Ludi Florales: this festival was established in 238 B.C. and became an annual event in 173, taking place between late April and early May. Of all the festivals, this one is almost a parody of it all, featuring a “reinterpretation” of circus games. For example, gladiator combats became mock fights between prostitutes. They were a kind of parody of circus games: instead of gladiator fights, there were mock fights between prostitutes and hares or goats or particularly licentious mimes.

Theatrical performances took place on temporary wooden structures built specifically for events inside the circus (where the Ludi were held), usually near temples or other public buildings. To have a permanent theater building, we would have to wait until 55 B.C., when the Theatre of Pompey was built in Rome near the area known today as “Campo dei Fiori”. The theatre was named after the Roman general and triumvir who financed it, probably to please the Romans in view of the upcoming elections (nihil sub sole novum.., “nothing new under the sun”…). A few years later, Julius Caesar, in order to rival his enemy, had a new theater built in the Campus Martius under the Campidoglio (the Roman Capitol Building), but it was not completed until under the Principate of Augustus. The theatre was named Theatre of Marcellus, after Augustus’ nephew, and it was inaugurated in 13 B.C.. Its remains can still be seen in the Jewish Quarter. This theater, which underwent many restorations under different emperors, was probably used until the end of the Roman Empire (476 A.D.). The last known renovation of the Theatre of Marcellus dates to 421 A.D.

Interestingly, theatre buildings started to be built at a time when productions started to lose popularity, or at least experienced less success than in the previous century. The causes must be sought in the ideological resistance towards theatre coming from the conservative political class, in power in Rome in the 3rd-2nd Centuries B.C., and represented above all by Cato the Censor. He was adamant about discouraging theatre as he perceived it as a distraction from war-like activities and civic duties, which any good Roman citizen should engage in. Classic Greek works in particular were mistrusted for their philosophical content and ideology. Other forms of entertainment – mostly games of various forms – were seen more favorably. Therefore, it is apparent how the Roman social landscape was quite different from the Greek one, where theatre was perceived as an instrument of civic and social education.

Because the wooden theatre structures had to be disassembled and reassembled each time, necessarily, the stage itself, between the mid-3rd Century B.C. and the mid-1st Century B.C., had to be simple and essential. The only permanent element was the altar, which is further proof of the original sacral character Roman theatre. From what we can gather from reading the plays and some texts from contemporary scholars, the stage most likely had a backdrop with two/three doors representing a temple, a palace, a cave for tragedies, and one, two, or three houses for comedies. Usually, the stage was oriented so that on the audience’s right side, there would be the forum (or the marketplace) while on the opposite side, there would be the countryside. The main curtain (auleum) was not introduced until 133 B.C., but, unlike modern usage, it descended at the beginning of the play and rose at the end.

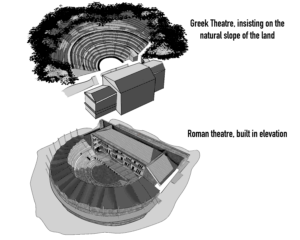

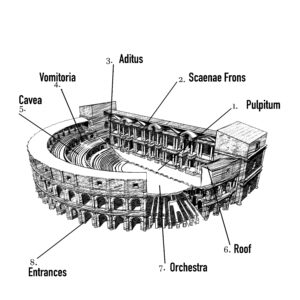

The permanent theatre building of the late republic and imperial ages, as we can learn from archaeological remains, is a semicircular self-standing structure, very much unlike the Greek theatre, which was built upon the slope of a hill. The Roman theatre features a narrower space dedicated to the chorus – as opposed to the Greek theatre – so that the tiers of seating areas (cavea) could be connected to the stage. While in the Greek Theatre, actors and audience would enter from the parodoi, open-air side passages between the seating area and the orchestra, in Roman theatres, these corridors were roofed. There were also more passages to access the cavea, which were called vomitoria. The stage (pulpitum) is closer to the ground than in Greek theatres and is overall much wider. The front of the stage sits on the diameter of the orchestra, which means that the orchestra itself is semi-circular rather than a full circle. Also, differently from Greek theatres, the orchestra at times provided seating for notable audience members. There was also a special box, facing the stage, for the emperor or for the organizer of the festival. When not used for seating, the orchestra was used by dancers, or for animal fights or other games..At the back of the stage, facing the audience, there would be a stone backdrop featuring several orders of columns and floors. At the stage level, there would be three doors; on the second level, there would be windows framed within columns and statues. The whole building was heavily decorated, to some extent, that was a way to counterbalance the cultural impoverishment and insignificance of the performances it hosted. As the seating area had no roof, large linen or silk tarps (velaria) were spread over the cavea to protect the spectators from the sun or rain starting at the end of the republican period. A detailed description of the theatrical buildings of the Imperial Age can be found in De Architectura (1st Century B.C.), a treatise written by Latin scholar Vitruvius.

Examples of this type of theatre from the imperial age can still be found in France or Spain, as they were wealthy Roman provinces at the time. Examples include the theatres of Nimes and Orange (France) or the theatre of Mérida (Spain). The latter is still in use today and hosts a famous Spanish theatre festival. This type of theatre should not be confused with the amphitheater, which is a fully elliptical building mostly devoted to hosting athletic events, circus games, and gladiator fights. The most famous example of an amphitheater is the Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum, which was inaugurated in Rome by Emperor Titus in 80 A.D.

When it comes to the structure of the play, the Romans followed the Aristotelian “rule of the third actor”, although in a less rigid way. It meant that there couldn’t be more than three actors on the stage, which does not exclude the presence of other silent characters or “ensemble” scenes. As in Shakespeare’s time, only men could act; hence, they had to pick up female roles as well. We have to wait until the fourth century to find evidence of the presence of women on stage. Scholars are divided about the use of masks in Roman theatre. Likely, however, masks were used in those plays that relied on mistaken identities or similarity between characters (e.g., Plautus’ Amphytrio or Menaechmi where there are twin characters). Acting was characterized by an almost total absence of realism, and the ability of the actor (actor or histrio, an Etruscan term that harkens back to the origins of Roman theater) was measured mainly in his use of the voice and his gestures. A good actor also had to be able to sing – and sometimes dance too – since in traditional plays the dialogue (deverbia) was often accompanied by music and included songs (cantica). On stage, there was always a musician playing the flute (tibicen, tibia player, a kind of flute with two reeds), who was usually both composer and performer. Unfortunately, there is no record of the times that have survived. Quite likely, the music was never written down and was learned by the actors “on the go”. Scripts were written in verse, although the meter depended on whether it was a song (lyrical verse), dialogue (iambic verse), or dialogue accompanied by music (iambic or trochaic verse).

Actors were organized into theatrical companies (catervae or greges) managed by the dominus gregis (literally ‘the master of the herd‘. Remember! The Romans were originally a people of shepherds and farmers, and so many terms in Latin reflect these origins. However, the troupe only had a few performers, among whom the leading actor stood out for his special skills. Some actors achieved great success, such as Pellione, interpreter of Plautus’ Bacchides, Ambivio Turpione, who acted for Terence, or Roscio, who was defended in court by Cicero with his defense speech “Pro Roscio comoedo”. The second and third actors played parts that did not require specific skills.

Troupes were represented by guilds, such as the Collegium scribarum histrionumque, for playwrights and actors, which was established in 207 B.C., and the Collegium tibicinum, for musicians and founded at the time of Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome.

Because it was believed that the actor’s trade was not suitable for a good Roman citizen, professional actors were mostly foreigners and slaves. If a Roman man wanted to be an actor, he would lose his citizenship, a fact that shows how theatrical practices in Rome encountered quite a lot of political and cultural resistance – at least in the Archaic and Republican ages.

Roman plays have been handed down to us partly directly in the form of manuscripts from the 5th Century onward and then throughout the Middle Ages until the 15th Century, and partly through the works of grammarians, commentators, and scholars, who reported partial fragments of plays that had not been confirmed otherwise. It is important to note that, whatever the case, we only have plays that were written down to be read, not performed. Troupes had “working copies” of the scripts, which likely looked very different. Yet, none of those working copies has survived.

Comedy

Of all the types of Roman comedies, the only ones that have survived are the “palliatae”, which are the ones with Greek subject matter and setting. The only thing we know about the “togata” comedy, the comedy of Roman subject matter and setting, is that it was introduced late and was short-lived, possibly because the conservative Roman society of the times could not embrace the subversion of values and social roles promoted by that kind of comedy within the boundaries of a local environment.

Following the Aristotelian tradition, the characters in comedies could only be ordinary people and slaves. The point of attack of the play is a conflictual situation leading to the mandatory happy ending. The plot always follows the same pattern: a character (or a group of characters) tries to win/have access to “something” (usually the love of a maiden, but also money) and to do so, obstacles must be overcome, usually through subterfuge and deception. A decisive role in the resolution of the intrigue is undertaken by a servant (servus callidus), usually the poet’s alter ego, who is ultimately also the author of the hoax. Compared with the Greek models, Roman comedies are more focused on the development of mask characters (stock characters) and on the fast, farcical pace, both distinctive elements of the Italic tradition.

Most successful Roman comedies date between the second half of the 3rd Century and the first half of the 2nd Century B.C.. At this time, Rome gradually expands into the Mediterranean with the Punic Wars and comes into contact with the Greek culture, thus also importing Greek plays that will be imitated and contaminated with each other.

The first major Roman playwright was the Neapolitan poet Gnaeus Nevius (270-201 B.C.), who is mostly remembered for his comedies, although he penned tragedies and historical pieces as well. Nevius was highly successful until he fell into disgrace for attacking the powerful Metelli family. Metelli imprisoned him and sent him into exile. This is likely the cause of the loss of most of his works, as only a few fragments have survived.

The only works that are available to us in an overall complete form are Plautus’ and Terence’s plays.

Plautus (254-184 B.C.)

Titus Maccius Plautus was born in Sarsina, central Italy, between 255 and 250 B.C. and died in Rome around 184 B.C. The last name “Maccius”, along with “Titus”, was probably added after his death to conform to the Roman name system. It recalls the name of a mask of the Atellana, thus suggesting that Plautus was also an actor.

Plautus was very popular during his lifetime and beyond, in fact, in the 1st Century B.C., nearly 200 years after his death, more than 130 comedies were circulating under his name. In reality, the grammarian Varro narrowed the number of Plautus’ authentic comedies to just 21, and these are the ones we still consider his own today. Most of those 21 comedies are complete, while some of them are incomplete. Scripts have been passed down to us through the medieval tradition in the following order:

- Amphitruo (“Amphitryon”): The god Jupiter wants to “spend the night” with Alcmena, wife of the Theban general Amphitryon. To do so, he assumes the identity of Amphitryon and is accompanied by Mercury, who assumes the identity of Sosia, Amphitryon’s servant. From the mistaken identity comes a most amusing game of misunderstandings.

- Asinaria (“The Comedy of Asses“): a young man wants to set his sweat heart, a prostitute, free. He succeeds with his servants and his father’s help, although his father becomes his rival in love.

- Aulularia (“The Pot of Gold“): the protagonist is the old miser Euclio, who is robbed of his pot of gold.

- Bacchides (“The Bacchides“): the protagonists are twin sisters. The deceptions triggered by two young men in order to win their love interest are complicated by the resemblance of the two women.

- Captivi (“The Prisoners“): the protagonist is an old man who manages to recover the two sons he had lost, one kidnapped as a child and the other taken as a prisoner of war. This play has more serious undertones and doesn’t feature any kind of romance.

- Casina (“Casina“): an old man falls in love with the same slave-girl his son is in love with. He eventually finds himself tricked (by his wife) into bed with a handsome young man instead of the girl.

- Cistellaria (“The Casket“): A young man, forced by his father to marry a maiden he does not love, is in love with a young slave girl, who will later turn out to be of free birth.

- Curculio (“The Weevil“): the protagonist is a parasite slave who helps his young master who is in love with a prostitute to trick the pimp and free the girl.

- Epidicus (“Epidicus“): Epidicus, a slave, helps his young master, who is in love with two girls.

- Menaechmi (“The Two Menaechmuses“): the protagonists are two identical brothers who do not know each other because they were separated at birth. One of the two, having happened upon the other’s town, takes his place without knowing it, with misunderstandings ensuing as a consequence of mistaken identities. Shakespeare takes it as a model for The Comedy of Errors.

- Mercator (“The Merchant”): A young merchant’s rival in love is his old father, who will ultimately not win the girl.

- Miles Gloriosus (“The Braggart Soldier“): The protagonist is a boastful soldier who will be cheated and robbed of his concubine. It is the archetype for many future portrayals of the vainglorious soldier, including Shakespeare’s Falstaff.

- Mostellaria (“The Ghost Play“): The servant makes the old man believe that his house is inhabited by ghosts so that he could protect his young master and his friends who are mingling with their sweethearts.

- Persa (“The Persian”): A slave dresses up as a Persian to help another slave succeed in tricking the pimp and setting his beloved free.

- Poenulus (“The Little Punic Man“): the protagonist belongs to a Carthaginian family, and the lovers eventually discover they are cousins and are reunited by mocking the pimp.

- Pseudolus (“Pseudolus”): Pseudolus is Plautus’ most successful and famous depiction of the character of the servant/slave. It is an alter ego of Plautus himself and a champion of deception to the detriment of the pimp.

- Rudens (“The Rope“): The play is set on the beach right after a shipwreck.

- Stichus (“Stichus“): a man has two married daughters whom he wants to push into divorce because their husbands are always traveling; the husbands’ return brings joy back to the family.

- Trinummus (“The Three Coins“): the protagonist is a young man who squanders his wealth and is eventually rescued thanks to the trickery of his father’s friend.

- Truculentus (“The Surly“): the protagonist is a prostitute who crafts a series of tricks to deceive her three lovers.

- Vidularia (“The Trunk”). There are only about 100 verses of the play that have survived, although they make it possible to figure out its plot. A young victim of a shipwreck will be recognized by the objects contained in a trunk found at sea by a fisherman.

Stylistically, Plautus’ work adds to the Greek model of the New Comedy a greater farcical component and characterization of the comedic stock characters (the servant/slave, the parasite, the young lover, the horny old man, the bitchy wife, the young prostitute, the old drunkard). This is probably a heritage of the Atellan Farce and overall of the Italic spirit. Another distinctive feature is the variety of the meter (verse) and the presence of songs, which make the plays look more like variety shows (similar to a modern-day recital), where comedic scenes are intertwined by a common thread.

Plautus has the goal of making his audience laugh, a goal he achieves perfectly even today. He makes people laugh with his use of language: he invents many words, uses puns, innuendos, the same names of the characters, and hyperbolic metaphors. Yet, it must be noted that Plautus is never crassly vulgar in language and does not use profanity or explicit references to sex and bodily functions. His comedy comes from caricaturizing his characters: the braggard s soldier, the miser. But he makes people laugh most of all because of the situations he crafts: the tricks, the misunderstandings, and the beatings. With Plautus, the stock character of the servant, already experimented with by Nevius, is brought to its maximum comic and expressive potential and ends up representing the playwright himself, in a metatheatrical way.

Most of the comedic elements Plautus banks on come from the society he lives in. He makes fun of the mercenary soldiers who fought in the Punic wars, the women who deceive their husbands, the fathers who fall in love with their sons’ lovers, the sons who squander their fathers’ wealth, and the foreigners – mostly the Greeks, but the Carthaginians as well – who compromise the Roman youth and society. Yet Plautus is perfectly integrated into the Roman society of the time, and he shares its conservative ideology. His comedies don’t aim at attaining an alternative reality, which is, on the other hand, exactly what Aristophanes tried to do with his works in the 5th Century B.C. Greece. Plautus’ comedies don’t want to subvert the existing social hierarchy: while the slave is the undoubtedly the protagonist of many of his plays and the women – mostly prostitutes, who are also slaves – deceive and trick the male characters, this does not mean that Plautus wants to advance an alternative social model or that he identifies as a rebel who wants to revolutionize his society. He is not interested in reforming gender inequality either. Plautus jokes about the vices and the obsessions of the Rome of the time, of which he feels a part, and keeps a conservative stance, which is why he is liked by his audience. He is recognized as someone like them.

Plautus’s work would go on to influence comedies of the following centuries. His works were translated as early as the mid-15th Century in Italy and throughout Europe. They were produced, adapted, and reworked. William Shakespeare read his works in Old English, and Plautus became a source of inspiration for many of his works, including The Comedy of Errors, which is a remake of Plautus‘s Menaechmi. Aside from that play, which is a true adaptation, many comedic devices Shakespeare uses come directly from Plautus, who indeed was the first to introduce them in Western Theatre. Such comedic devices include the comic duo (and the twins), which trigger mistaken identities, the use of the aside, and the compulsive beatings.

Terence (195/185-159? B.C.)

Publius Terentius Afer (Terence) was born in Carthage, North Africa, around 190 B.C., which is a generation after Plautus. Terence was of Berber ethnicity, which would make him the first non white Latin poet. We have this information thanks to Roman Imperial historian Suetonius, who writes De Viris Illustribus (On Famous Men) and dedicates the section Vita Terenti (The Life of Terence) to Terence. In this section (chapter 5), Suetonius describes Terence as colore fusco (of dark complexion). He arrived in Rome as a slave and, thanks to his beauty and talent, soon became a free man. He mingled with the Roman upper classes and the nobles, particularly with the Scipiones family, who were strong advocates of Greek culture and had more progressive views in politics. The Scipiones still represented a minority when it comes to social/political and cultural views, as the greatest change would occur later.

Terence died in 159 B.C. at a young age while he was traveling in Greece and Asia Minor. He wasn’t even 30. This implies that there are only very few plays he left behind that have survived. The following six plays are all that we have, and they were probably written between 166 and 160 B.C.:

- Andria (“The Woman from Andros“): the protagonist is a young woman from the Greek Island of Andros, who is loved by young Panfilo, whom she doesn’t love back. Yet, thanks to the servant Davo, Panfilo succeeds in winning her love and marrying her.

- Hecyra (“The Mother-in-law”): The protagonist is a mother-in-law who goes out of her way to resolve the disagreements between her son and his sweetheart.

- Heauton Timoroumenos (“The Self-Tormentor“): Old Menedemus self-punishes by condemning himself to hard labor because he had opposed his son’s marriage, which led the young man to enlist in the army and be deployed in Asia.

- Eunuchus (“The Eunuch”): The protagonist pretends to be a eunuch to get the custody of the woman he loves from the soldier who owns her.

- Phormio (“Phormio“): Phormio is a parasite who, through a series of controversies, will help two cousins marry the women they are in love with.

- Adelphoe (“The Brothers”): Two brothers are at odds over educational methods for their children, one being more liberal, the other more strict.

Terence draws his plots from the Greek New Comedy, similarly to Plautus. Some of the features he used are: complicated love stories, deceptions, misunderstandings, and reconciliations. Yet, Terence is less popular than Plautus among the Roman audience, who criticize him and would rather attend circus games than see one of his plays – we learn that from Terence’s own words in the prologues of some of his plays. Terence’s comedies are deeply influenced by the new values settling in Rome after the increasing cultural exchanges with the Greek world as a consequence of the colonization wars of the 2nd century B.C. Terence embraced the new concept of the “man-to-man” respect, the respect for the different, a liberal approach to the education of children, and a greater sensitivity to women. In a way, he was too much ahead of his time to be fully appreciated by his contemporaries. He provided greater psychological and human depth to his characters and addressed social issues rather than being preoccupied with just making people laugh. And indeed, even today, Terence’s comedies still don’t read wildly funny.

Terence’s new sensibility, along with his simpler and more elegant use of language (as opposed to Plautus), made him a very popular read in the Middle Ages, when he was considered a model for the Medium Style.

Tragedy

Latin theatre, along with all the Latin literature, originated with Livy Andronicus’ tragedy Odusia, a Latin translation in Saturnian verse (a typically Roman verse) of Homer’s Odyssey, which was produced in 240 B.C.. However, Romans were never too fond of tragedies, being more inclined to indulge and develop farcical comedies, which in the end are more akin to the Italic culture.

True to the tradition of the genre, the characters in Roman tragedy include gods, heroes, kings, and mythological characters, while the plot develops from a prosperous beginning into a dramatic ending. The Latin poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known as Horace (65-8 B.C.) in his Ars Poetica – a treaty in verse about the rules of poetic composition- while reviving the Aristotelian theoretical regulations, also provides a long dissertation about theatrical compositions (vv. 153-294), with a specific focus on the genre of tragedy. Horace confirms the cathartic goal of tragedy and provides its composition and staging features, including the five-act structure. Such detailed descriptions and instructions seem to indicate that Horace meant to guide new dramatists and playwrights in the hope of a revival of the genre during the reign of Augustus.

Rome witnessed a flourishing season for the tragic genre during the republican period, featuring playwrights such as Naevius and Ennius in the archaic age and Pacuvius and Accius in the late republic. Naevius invented the tragedy of Roman subject matter (praetexta), while Ennius (239-169 B.C.) established the canons of style and content for the tragedy of Greek mythological subject matter (cothurnata), which stayed true until tragedists Pacuvius (220-130 B.C.) and Accius (170-86 B.C.). Not much has survived of the works of these playwrights, aside from a few fragments and titles, and maybe that is not so unfortunate.

The only Roman playwright writing tragedies whose body of work has survived in its completeness is the philosopher Lucius Anneus Seneca (4 B.C.-65 A.D.).

Seneca (4 B.C.-65 A.D.)

I, Calidius, CC BY-SA 3.0

Lucius Anneus Seneca was born in Cordova, Spain, at the very beginning of the 1st Century A.D. He was the son of the rhetorician Seneca the Elder. He was educated in Rome, where he lived under the reigns of Emperor Claudius (who sent him into exile in Corsica for 8 years, from 41 to 49 A.D.) and Emperor Nero, serving as his tutor for the first 5 years of the empire. In 62 A.D., he was forced to retire to private life, and in 65 A.D., he was forced into suicide on Nero’s orders. He was one of the greatest philosophers of Antiquity and a follower of the Stoic doctrine, which made him a popular reading for the early Fathers of the Christian Church, which were sympathizers of the Stoic ideals, in particular in regards to the providential concept relating the wordily matters and the existence of one and only god.

Of all his works, what remains today are philosophical treatises and dialogues, a collection of letters addressed to his friend Lucilius, and 8 tragedies of Greek subject and setting (cothurnatae), based on Greek myths:

- Agamemnon (“Agamemnon”): The play tells the story of the Greek hero Agamemnon, who returns home victorious from the Trojan War with his slave Cassandra and is killed by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus.

- Hercules Furens “The Mad Hercules”): Juno casts a spell on Hercules, making him insane. When he comes back from the underworld, he kills his wife and children. When the spell fades away and he returns to his senses, he finds out what he had done and attempts to kill himself, but he is stopped by his father and a friend.

- Medea (“Medea”): the sorceress Medea kills the Corinthian King Creon, his daughter Creusa, and her children to punish her husband Jason, who had rejected her to marry Creusa. Medea leaves Corinth by flying away on her father’s chariot of the Sun.

- Phaedra (“Phaedra”): Phaedra, the wife of King Theseus, is made to fall in love with her stepson Hippolytus by Aphrodite. Hippolytus rejects her, and she proceeds to accuse him of assaulting her. Her husband, Theseus, is outraged and asks the god Poseidon to help him punish his son. Hippolytus is thus killed, but Phaedra also kills herself out of remorse.

- Phoenissae (“The Phoenician Women“): the title alludes to the Phoenician women who were held captives and were destined to serve the god Apollo. They were the protagonists of Euripides’ tragedy by the same title. This play has come to us in a fragmentary form. We only have two complete scenes: in the first Oedipus one, accompanied by his daughter Antigone, intends to return to Mount Cytheron where he had been abandoned as a child; in the second one Jocasta, aided by Antigone, succeeds in averting a war between her two sons but he fails at restoring peace between them.

- Thyestes (“Thyestes“): Mycenae’s king, Atreus, takes revenge on his brother, Thyestes, who is guilty of taking his kingdom away from him, by killing his children and having them served to him as part of a meal.

- Troades (“The Trojan Women”): The play is about the Trojan women, particularly Hecuba, Polyxena, and Andromache, after the defeat of Troy by the Greeks.

- Hercules Oeteus (“Hercules on Mount Oeta“): Hercules is poisoned by his wife Deianira, who is jealous of Iole, her young rival in love. He climbs Mount Eta and, in excruciating pain, sets himself on fire after learning that Deianira kills herself.

Aside from Thyestes, all of Seneca’s tragedies follow the Greek model. There is another play, Octavia, whose manuscript bears the name of Seneca, yet scholars believe that it is more likely the work of an anonymous rhetorical master, past Nero’s reign. The play is inspired by the tragic end of Nero’s young wife, and it is interesting to us because it is the only tragedy of Roman subject matter (praetexta) that has survived in a complete form.

The timeline of Seneca’s tragedies is not known to us. Quite likely he wrote them after he retired from Nero’s tutelage, alternating them with his philosophical treaties, in which is mostly discusses his Stoic views and how he wishes to implement them within the Roman society. Specifically, he advocates for the implementation of virtue (virtus) and the exercise of free will as a defense against the violence of the passions (furor), such as wrath, the blind desire for revenge, wild eros, and the craving for power.

Seneca’s tragedies retain the verse type and structure of the classic Greek tragedy, being divided into episodes and choruses. Likely, they were not written to actually be performed, but rather to be read in public gatherings. By Nero’s time, traditional theatre was declining in popularity in favor of mime performances, circus games, and gladiatorial combats. Because of this kind of “competition,” Seneca’s works tend to be quite gruesome, with many “splatter” scenes that include massacres, cannibalistic banquets, and blood baths, very much in the style of Quentin Tarantino’s movies. He likely did that to “challenge” his competition and appeal to the taste of his audience.

Although Seneca didn’t specifically write for production, his plays do retain strong theatrical features despite the sometimes excessive use of rhetoric. Because Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides’ tragedies didn’t have much (or any) exposure until the Renaissance, because of the language barrier (the Greek language was not well known in Rome), we owe the birth of the “modern” tragedy to Seneca’s works.

Modern theatre owes Seneca for the invention and implementation of some of the tragic devices, such as ghosts, revenge, subterfuge, power dynamics, incestuous passions, murder, and poisonings. Yet, the most relevant achievement in Seneca’s work is the creation of a much more modern tragic character. In classic Greek theatre, the hero is a one-dimensional, never-yielding character, and he is always a man. Instead, in Seneca’s works, the hero – man or woman – is much more conflicted, has inner struggles and emotional insecurities and second thoughts, particularly in the most climactic moments – when they are close to committing the crime.

Seneca’s tragedies have inspired many famous later playwrights, such as Shakespeare, Sarah Kane, and Caryl Churchill.

The Classics on Broadway

Because of the blending of music and dialogue, Plautus’ plays could remind us of modern musical theatre. Indeed, several contemporary musicals took inspiration from his works, the most famous being “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” a musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and libretto by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart, which is loosely based on Plautus‘ comedies Pseudolus, Miles Gloriosus, and Mostellaria. The musical premiered on Broadway in 1962 and ran for 964 performances. Then it toured to London (West End) and even to Australia. It won seven Tony Awards and was so successful that in 1966 it was also adapted into a movie starring Zero Mostel and directed by Richard Lester. Although some of the satire and the depiction of female characters are not in line with today’s social sensibilities and appropriateness, the musical continues to be extensively produced.

Plautus is not the only author from ancient Rome whose works have been adapted for the Broadway stage. The musical Hadestown, with music and lyrics by Anais Mitchell, is inspired by Virgil’s poetic depiction of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The musical tells the indie-punk tale of Orpheus’ journey to the Underworld to get his beloved Eurydice back, in a post-apocalyptic setting loosely inspired by the Great Depression. The musical debuted Off-Broadway in 2016 under the direction of Rachel Chavkin and, after numerous revisions, moved to Broadway in 2019. It was nominated for 13 Tony Awards and won 8 of them, including Best Musical.

Takeaways

- Roman theatre, like Classic Greek theatre, originated in the context of religious practices and was performed as part of public festivals, often dedicated to the gods.

- In early plays, especially in comedy, the Italic cultural component merges with the Greek. Italic cultural components include the taste for farce, the introduction of stock characters, and the introduction of songs.

- The permanent theatre building in Rome was built only in 55 B.C. (Theatre of Marcellus) because there was ideological resistance to theatrical activities. Earlier, performances were held in wooden theatres that were assembled and disassembled when needed. The stage of these theatres was very simple.

- In Rome, theatre is seen as entertainment and distraction, not as a means for social growth and civic insight for the citizens, as it was in ancient Greece.

- Alongside traditional theatre, which flourished mainly in the 2nd and 1st Centuries B.C., there were other forms of entertainment in Rome that were more popular, even in the imperial age, such as mime, Atellana (a kind of Commedia dell’Arte), pantomime (ballet), circus games, and gladiator fights.

- The actors were only men, mostly foreigners or slaves. Women were allowed to act only in mimes.

- Most of the complete plays that have survived are mainly comedies on Greek topics (palliatae): 21 by Plautus, 6 by Terence, for a total of 27 comedies, which featured a combination of dialogue and songs.

- The only complete tragedies that have survived are Seneca’s, for a total of 8, and all of which were inspired by Greek models (cothurnatae).

- Octavia, which for a long time was falsely attributed to Seneca, is the only tragedy on a Roman subject that we know of (praetexta).

- All of the other playwrights of the time are only known by their names or because of a few fragments of text, as nothing else has survived.

- Plautus is credited with introducing most of the comedic devices and mechanisms that are still in use for that genre in modern theatre.

- Seneca is credited with introducing most of the tragic devices and mechanisms that are still in use today for that genre in modern theatre.

- William Shakespeare was inspired by Plautus for comedies and by Seneca for tragedies.

Vocabulary

Atellana

Etruscans

Greeks

Palliata

Togata

Cothurnata

Praetexta

Mime

Pantomime

Circus games

Gladiator combats

Marcellus Theatre

Colosseum

Choirs

Cantica

iambic verse

Livio Andronico

Nevius

Plautus

Terence

Seneca

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

Let’s investigate the stylistic connections between Seneca’s tragedies and splatter/horror movies.

Seneca’s tragedies feature scenes of extreme violence and psychological intensity, which anticipate in many ways what will be the key elements of splatter horror movies. Let’s analyze the cultural, philosophical, and emotional functions of that kind of graphic violence in both traditions.

Students should read the banquet scene in Seneca’s Thyestes and the infanticide scene in Seneca’s Medea.

Students should watch splatter scenes from movies such as Evil Dead, Saw, and Hostel (the instructor and the students could suggest other titles as well).

Students should then discuss the specific features of both Seneca’s style and the horror movies to find similarities, differences, and outcomes.

A follow-up discussion should focus on how students reacted to READING the violence as opposed to SEEING it on screen. (Remember! Seneca’s work was likely read out loud rather than performed!)

The instructor should divide the class into two different groups, the first including those students who preferred READING the violence, and the second including students advocating for seeing it on screen.

Both groups should make their arguments, trying to contextualize their reactions in order to make them more objective.

Students should discuss whether Seneca’s tragedies -such as Thyestes and Medea- would lend themselves to a screen adaptation.

If time allows it, in a second session, students should be divided into two new groups.

Group 1 should read Thyestes as homework, while Group 2 should read Medea.

When in class, the two groups should work together to create a storyboard – a sequence of vignettes of the scenes of the play- so that they could visually tell the story of the play to the other group.

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 509 B.C. | Founding of the Roman Republic | Transition from monarchy to republic; Rome begins to expand politically and culturally, setting the stage for future artistic and theatrical developments. |

| c. 364 B.C. | Etruscan performances | Early form of ritual performance introduced to Rome; marks the beginning of theatrical activity tied to religious festivals. |

| 240 B.C. | Livius Andronicus wrote the first Latin play | Adaptation of a Greek play into Latin; recognized as the beginning of Roman literary drama. |

| c. 205–184 B.C.

(approx.) |

Plautus Writes Popular Comedies | His plays use slapstick, music, and stock characters; shape Roman comedy and influence future playwrights, including Shakespeare. |

| c. 170–160 B.C.

(approx.) |

Terence wrote and staged literary comedies | Introduces refined language and complex characters; emphasizes moral themes and education. |

| 146 B.C. | Roman Conquest of Greece | Roman exposure to Greek drama and aesthetics increases; Hellenistic influence on Roman theater architecture and literature grows. |

| 55 B.C. | Pompey Builds First Permanent Stone Theater in Rome | A major turning point—transition from temporary wooden stages to permanent venues; the theater becomes central to Roman public life. |

| 27 B.C. | Start of the Roman Empire Under Augustus | Augustus uses theater to promote state ideology; he funds lavish spectacles and performances as part of imperial propaganda. |

| 13 B.C. | Theatre of Marcellus Dedicated | State-of-the-art venue commissioned by Augustus, an enduring model of Roman theater architecture. |

| 1st–2nd Centuries A.D. | Height of the Roman Empire | Public entertainment dominates; pantomime and mime rise in popularity as literary drama declines. |

| c. 100–200 A.D. | Pantomime Becomes the Primary Theatrical Form | Lavish solo performances with music and dance attract large audiences; spectacle overtakes storytelling in public favor. |

| 313 A.D. | Edict of Milan: Christianity Legalized by Constantine | Theater begins to decline as Christian leaders condemn it; actors and performances are associated with immorality and paganism. |

| c. 400–476 A.D. | Fall of the Western Roman Empire | The collapse of the empire leads to the end of Roman theatrical institutions; theater largely disappears to re-emerge as liturgical drama in the Middle Ages. |