9 Chapter Eight – English Restoration and 18 Century England

Chapter 8 – English Restoration and 18th Century England

Introduction

Brief historical background

After Queen Elizabeth died with no direct heirs in 1603, the throne was passed on to King James VI, who was the king of Scotland and the first king of the House of Stuart. He governed until he died in 1625, and was followed by his son, King Charles I.

King Charles I was not a popular king, and many scholars and historians believe he was the cause of his own demise. He didn’t accept and sided with the political power of the English Parliament and claimed he had the “divine right of kings” to rule the country according to his fancy, which basically made him an absolute monarch. His deliberations about taxes and his dubious religious views particularly angered the Parliament and the people, and eventually, the resentment culminated in the First English Civil War in 1642. The king’s army was defeated in 1645 by the New Model Army, which had been formed by the Parliament, which had recruited army veterans and soldiers with strong religious beliefs, such as the Puritans, and anti-royalists. King Charles I was imprisoned as he refused to abide by a constitutional monarchy (big mistake!). He briefly escaped his captivity, but eventually was imprisoned again on the inescapable Isle of Wight. After being tried and found guilty of high treason, King Charles I was executed in 1649. At that point, Charles I’s son, Charles II, was proclaimed king by the Scottish Parliament in a desperate attempt to save the monarchy. Yet the new king’s army was also defeated by the New Model Army, leading him to escape to France and leave both England and Scotland to be ruled by the English Parliament, who established a republican government under the name of the English Commonwealth. Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) was appointed Lord Protector (Head of State) and governed the country under an iron fist and very restrictive religious and social rules until his death. During this time, all theatrical activities were banned, theatres were closed, and actors were outlawed and persecuted. Theatre didn’t disappear altogether, but it surely kept a very low (and secretive) profile. Some artists managed to escape the Puritans’ regulations by advertising their productions as concerts and musical events, as music was not completely prohibited. Others, like William Davenant, used their own homes as the venue for their performances.

Oliver Cromwell died in 1658 as a result of malaria and a kidney-related disease. He had refused to use quinine, the only treatment for malaria known at the time, because it had been discovered by Jesuit missionaries. Cromwell’s son, Richard, came to power, but he didn’t last long since he had no support from either the people or the Parliament. Besides, the English people had grown weary of all the restrictions of this new form of government, which eventually led to the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 with the return from exile of King Charles II. As the new King of England and Scotland, Charles II immediately took it upon himself to limit the power of the Parliament, to avoid what had happened to his father. He was successful in his reign until his death, when the throne passed on to his brother, James II. Yet, James II converted to Catholicism and baptized his only son, which was perceived as a threat to the English Protestant Church by the English Parliament. The Parliament then reached out to James II’s protestant daughter Mary, who was married to William of Orange, and with the so-called Glorious Revolution, James II was deposed and William and Mary rose as the new monarchs of England in 1688.

Most historians and scholars believe this marks the end of the Restoration in the arts, while for theatre, it could potentially extend into the early 18th Century.

King Charles II was a strong supporter of the arts and theatre, so very early into his monarchy, all theatrical activities resumed and grew stronger than ever before… although the field was quite strongly regulated by the monarchy. First, companies could only perform legally if they received a license (or patent) from the king, who directly issued them, but only to two theatre companies. The first company was directed by William Davenant (1606-1668) and the second one by Thomas Killigrew (1612-1683). This patent provided Davenant, who was allegedly Shakespeare’s godson, and Killigrew with the monopoly of theatrical activities in London. Killigrew’s company was named The King’s Company because of his loyalty to the crown, even during the king’s exile, while Davenant’s sponsor was appointed to be the Duke of York, the king’s brother.

As the position of the Elizabethan Master of Revel was reinstated, the king allowed Henry Herbert to regain the position, as he was the last Master of Revel before the Commonwealth. Yet, he was only allowed to issue licenses to companies outside London, and when he died (1673), his position was taken by the same Thomas Killigrew.

In short, Davenant and Killigrew had complete control and monopoly of all theatrical activities within the city limits of London.

Killigrew’s The King’s Company was populated by the most famous and navigated actors, most of whom had been popular before the Civil War. Davenant’s company, on the other hand, mostly relied on younger actors and somewhat invested in training. Both companies were very prolific, but Killigrew didn’t have a good eye for the business itself, and his company struggled financially until the only way to survive was to merge with Daventat’s company.

A big change introduced by King Charles II was to allow women to act. He did it through a warrant dated 1662. Quite likely during his nine years in exile in France, Spain, and Holland, the king had seen several productions featuring women acting on stage, as most countries in continental Europe allowed that, and thought that England should do the same.

Up until then, female roles had been played by young boys who underwent specific training and used stylized movement patterns that represented shared conventions with the audience. Clearly, with women playing female roles, productions became more realistic, yet the reputation of actresses often still suffered from social prejudice. In short, actresses were considered a little more than courtesans and a little less than prostitutes. For example, it was common practice to allow male patrons into the actresses’ dressing rooms for an extra fee so that they could see them changing…. And possibly for some other attention.

Coincidentally, the rise of actresses caused many of the “boy players” (the male actors who previously played female roles) to fall out of fortune, as most of them could not adjust to playing male parts. One notable exception is Edward Kynaston (1640-1706), who became famous in the upper circles of society for his ambiguous sexuality and stunning representations of female characters (on and off stage) to the point that Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), a British writer and politician who documented most of the social life of the time through his personal diary, described him as “the loveliest lady that I have ever seen in my life” as well as “the handsomest man.”

Kynaston was able to pursue his career playing male roles, and he retired in 1699.

Generally speaking, the acting style of both the Restoration and of the whole 18th Century was still far from realism. Actors relied more on rhetorical delivery, spoke directly to the audience, and utilized wide and over-the-top gestures to emphasize emotions and punctuate their lines, creating patterns in the staging that mirrored well-established conventions.

Theatre companies during the Restoration and the 18th Century featured more company members than had previously happened in the Elizabethan time, and instead of reprising the sharing plan, they opted for contracts that would specifically apply to each production and each actor. On several occasions and for some of the better-known actors, contracts were supplemented by the so-called “benefit performances”. A benefit performance would give all the box office money to the actors, thus increasing their earnings.

This shift in the management of the theatre would slowly but inevitably deprive the actors of exercising some control over the company. Theatre managers, like Christopher Rich (1657-1714), who managed both the Drury Lane and the Lincoln’s Inn (later the Covent Garden) theatre, became more businessmen than theatre artists, in a way resembling a modern-day producer. This trend would continue all throughout the century.

Playwrights were not usually part of the company. Instead, they were commissioned to write plays and paid a flat fee by theatre companies. Once the play was in performance, it fully belonged to the theatre company. At times, playwrights were included in the “benefit system” as a way to increase their earnings, but that wasn’t the norm, and, most importantly, there was little to no protection of the playwrights’ intellectual property. The Statute of Anne, also known as the Copyright Act of 1709, provided playwrights (and authors in general) with some leverage on their work, although it mostly addressed the rights over the manuscripts between the authors and the publishers.

An interesting evolution in the dynamics of theatrical companies happened in the second part of the 1700, when David Garrick (1716-1779) rose to prominence not only as a well known and respected actor but also as someone who would be involved in all aspects of a theatrical production – in a way resembling what would later become the role of the director.

Garrick starred in a multitude of roles, including several of Shakespeare’s plays. He became a company member at the Drury Lane theatre, where he also functioned as a manager and occasionally as a playwright, as he adapted many of Shakespeare’s plays for his contemporary audience. He would stay with the Drury Lane, on and off, for his entire career.

He came from a middle-class family of French origins. He grew up in Lichfield, where he attended the local Grammar School. Later, he enrolled in the esteemed Edial Hall School, directed by Samuel Johnson, where he learned Greek and Latin and discovered his passion for the theatre. He soon moved to London with his younger brother George and started a wine business, which didn’t flourish. Instead, his acting career took off, and he quickly became one of the most sought-after actors of the time. He “specialized” in Shakespeare, as he deeply admired him: his portrayal of Richard III is allegedly what got him into the Drury Lane. Garrick had several affairs but only really loved one woman, Eva Marie Veigel, whom he married in 1749. The couple lived a happy life, and Garrick acquired great wealth along with his popularity, which allowed him and his wife to have a high-end lifestyle.

He died possibly because of the consequences of a “bad cold” in 1779 at the age of 62. His wife would outlive him for another 43 years. Garrick was buried in the Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey, a demonstration of the fame and respect he had gained in his life.

Garrick is remembered for attempting to introduce a more realistic style of acting, which came from his consistent observation of human nature and society.

He advocated for more character and time-appropriate costuming and stated the importance of research to support the arc of the characters. As a manager and a “director”, Garrick introduced a more rigorous rehearsal process. Actors were asked to arrive on time, know their lines, and engage in rehearsals for several weeks. If they didn’t abide by these rules, they would be fined.

Aside from costumes, it is believed that Garrick also contributed to other aspects of theatrical design. For example, he introduced the use of masking to hide the lights (candles), and he completely banished the audience from the stage.

Finally, Garrick is responsible for really celebrating the works of William Shakespeare. In 1769, he organized the Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon, celebrating the 200th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. The event will become a milestone in the process of officially proclaiming the Bard as the English national poet.

NELL GWYN

Thomas Wright, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nell Gwyn (1642 or 1650- 1687) was an English actress who is remembered for her beauty, her wit, and her “Cinderella story”. She rose in popularity for her comedic roles, eventually notably becoming King Charles II’s mistress, bearing him two sons, whom the king recognized and endowed with dukedoms.

Her early days and career are somewhat surrounded by mystery because of the lack of records and factual data, as opposed to a myriad of unverifiable sources. She is believed to have come from a poor family and to have lived in London all of her life, specifically in the slums of the Drury Lane area. In her younger years, it has been reported that she experimented with cross-dressing, picking up the name of William Nell. It has been speculated that her mother ran a brothel, although it has not been proved that Nell worked in it as a sex worker. According to some anonymous and unverified sources, she was a street vendor. She was in a brief and tumultuous relationship with a man named Duncan, who accommodated her in a modest room over a tavern.

Apparently, she was exposed to the theatre because at some point she sold oranges to the audience at the Theatre Royal, in Drury Lane, which was home to the King’s Men, the company led by Thomas Killigrew, who eventually hired her to act in his company.

During her first years in the company, Gwen – who was illiterate – learned the craft.

Her first official appearance on stage was in John Dryden’s The Indian Emperor, where she played the role of Cydaria, the daughter of the emperor. Yet, her fame came from playing comedic roles in the very popular comedies of the time alongside her partner, fellow actor Charles Hart.

In 1667, she charmed Earl Charles Sackville, who maintained her for a few years lavishly. The affair with King Charles II started a year later, after he had seen her act and invited her for supper. The story goes that the dinner turned “sour” as the king had forgotten his purse at home and Gwen had to pay the bill. Despite starting on the wrong foot, the king and Gwen became lovers, and she used to call him “Charles III” as he was the third “Charles” in her life (after Charles Hart and Charles Sackville).

She stopped acting around 1670, probably because she was taking care of her children and because she didn’t need it anymore: the king had granted her a stipend and a townhouse in Pall Mall, which stayed in her family until the end of her century. The king also gave her a house in Windsor, so that she could be there when the king was at Windsor Castle.

Her relationship with King Charles II lasted until his death, and the king’s successor and brother, James II, obeyed his brother’s wish not to let “poor Nelly starve.” She was assigned a yearly allowance of 1500 pounds.

In the last years of her life, despite the wealth and the notoriety, Neil Gwyn suffered several misfortunes. She had two strokes, the first one leaving her half paralyzed, and the second one a few months afterwards, confining her to bed. She died a few months later in November 1667 at the age of 37. The cause of death was apoplexy due to syphilis.

Nell Gwyn’s life has inspired countless plays, novels, short stories, documentaries, and movies.

RESTORATION DRAMA

The name “Restoration Drama” applies to all the theatre that was written and produced from the re-establishment of the monarchy in 1660 until the very beginning of 1700.

Due to the Civil War and the Commonwealth period that had seen theatrical activities reduced to the minimum, when theatres reopened, the first issue that they had to face was the lack of new plays being produced and staged. Clearly, there was plenty of previous material – including Shakespeare’s plays and subsequent re-arrangements – but there was nothing that spoke to the new sentiment of the time.

This led many authors and scholars to start writing almost compulsively, and for the first time, that included quite a few female playwrights. Some of these women include Katherine Philips (1632-1664) who is credited to be the very first to have a play, Pompey, being produced by a professional company (in Dublin); Frances Boothby (died 1669) who was the first woman to have her play Marcelia produced in London (by the King’s Company), Elizabeth Polwhele (1651-1691) and later and most notably, Aphra Behn (1640-.1689). Of course, there were also quite a few men writing plays, among whom the most prolific and successful was John Dryden (1631-1700), who excelled in writing all sorts of literature. Other playwrights of the time are Sir George Etherege (1634-1691), William Wycherley (1641- 1715), and William Congreve (1670-1729).

When it comes to serious drama, in the latter part of the 1600s, we have “heroic tragedies”, also known as “heroic drama.” Those plays were heavily influenced by Spanish and French Renaissance drama and focused on conflicted love stories and honor. They were often set in exotic environments and featured heightened language and verse. Characters were borderline stereotypical, with a hero (or heroine) who needs to overcome some tragic flaw that would otherwise bring dishonor to themselves and their legacy.

Michael Vandergucht, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

John Dryden wrote several heroic tragedies, like The Indian Queen and the Indian Emperor, yet this genre’s fortune declined quite fast in favor of more approachable plots and language. The Neoclassic principles were brought to the table again, although English writers didn’t abide by them in the strictest way possible – the way it was happening in France, for example. Dryden penned some of these new styles of tragedies, the most famous one being All For Love (1677), which is inspired by Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra.

Yet, what the English Restoration Theatre is really remembered for is the evolution of comedies, in all of their varieties. We have comedies of “humours” that followed and further developed Ben Johnson’s theories, comedy of manners, farces, and comedies of intrigue. All of these style of comedies have common elements, such as a more contemporary use of language, witty – but somewhat stereotypical – characters, fast pace, a widespread use of (sexual) innuendos, subterfuges and bawdiness, and, of course, a happy ending – which doesn’t necessarily re-establish the former social hierarchy. An interesting aspect of theatrical activities and audiences of the time was that this new and bold approach was mostly enjoyed by the same social classes that were the target of the theatrical satire, particularly at the beginning. Later, when the excitement for the end of Commonwealth restrictions cooled off, restoration comedies faced a moral backlash which would eventually lead to tamer and more “socially correct” comedies in the 18th Century.

John Dryden, once again, authored several comedies, mostly focusing on comedies of manners, where he targeted the vices and habits of the upper classes and viciously made fun of them. Some of his famous titles include The Marriage à la Mode and The Mock Astrologer. Another writer focusing on comedies of manners is Sir George Etherege (1634-1691), whose The Man of Mode (1676) represents the peak of this genre.

Aphra Behn wrote at least seventeen plays, alongside other forms of literature. She is mostly known for her comedies of intrigue, specifically for The Rover (parts 1 and 2), which is still popular to this day and which many consider to carry a feminist agenda.

The play features three very strong female characters who, unlike the trend of the time, take their future into their own hands in order to achieve their happiness.

The action is set in Naples, where two wealthy Spanish sisters, Hellena and Florinda, arrive with their families to participate in the local Carnival. Florinda is being married off by her father to a much older man. Alternatively, she could marry her brother’s friend. Yet, none of those options fancied her, so through her own actions, she succeeds at marrying her true love, Colonel Belville. Being the second daughter, Hellena was supposed to retire in a convent and become a nun again, which was not exactly her first choice. Instead, she manages to seduce the rover and gets him to marry her.

The third character represents the lower class: Angelica Bianca, a courtesan. A strong woman, Angelica picks her own customers and sets her own price, becoming her own manager. When threatened, she doesn’t hesitate to pull out a gun to “set things straight.”

The two plays that probably best represent this period and that are still frequently produced today are William Wycherley’s The Country Wife and William Congreve’s The Way of the World.

William Wycherley (1641-1716) was an officer who enjoyed writing plays and poetry, both activities he considered hobbies. He was from a middle-class family and was educated, first at home, and then sent to France to finish his military education. He served in the Royal army as a captain lieutenant, later promoted to full captain, and later resigned in 1674, going back to London. He engaged in the social life of the time, also gaining the favor of King Charles II, who hired him to tutor one of his illegitimate sons.

Wycherley’s most famous play is The Country Wife. The play was written between 1672 and 1673 and was published the year after that. It is a harsh satire of the lasciviousness and the hypocrisy of the British aristocracy, featuring very explicit sexual content. The most notorious “scandalous” scene being the “china scene”: where Horner and Lady Fidget are in the next room (off stage) supposedly admiring Horner’s china collection –code language for having very loud sex–, while the clueless Lady Fidget’s husband innocently waits outside their door (on stage) for his wife to come back.

The play is centered around Harry Horner (take notice of the last name….), who pretends to be impotent to be admitted into the private circles of Lady Fidget (another interesting last name), a married woman. Horner’s goal is to seduce as many “respectable” women as possible by cuckolding as many husbands as possible. His plan works quite well, also because of the “support” he receives from the women themselves, who are eager for a sex life outside their frequently unhappy and arranged marriages. In the end, Horner is almost called out by Lord Pinchwife. Yet, Horner explains to him that if he embraced the belief that Horner was not impotent, then he would be forced to consider the fact that his wife could have been cheating on him. So, to preserve his reputation, Horner advised Lord Pinchwife to go along with the lie. As you can see, the ending exposes the hypocrisy of Wycherley’s society about reputation and social norms.

Take note that most of the characters in the play have names that hint at the characters’ hidden (or not so hidden) desires and behaviors: Horner, Pinchwife, Lady Fidget, Lady Squeamish….

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William Congreve (1670-1729) belonged to the British upper class and served in Parliament, alongside being a respected playwright, poet, and satirist. His writings criticize the vices of his social class, although he distances himself from previous writers, such as Wycherley, for a more elevated style of writing and a tamer approach. Congreve’s work is often considered the “bridge” to what would become the style of the 18th Century, when comedy settles into more moral dramatic circumstances, more defined characters, and stylized language.

Congreve’s masterpiece is The Way of the World, which was written and produced in 1700, originally with little success. While the play still explores some of the more popular aspects of the Restoration – such as adulterous relationships and misunderstandings – it does provide a happy ending that restores the “greater good”, with evil characters being punished and the young lovers enjoying their earned happy ending.

Drama of the 18th Century

With the reign of William and Mary, the English society started to move away from the “explosion of liberalism” that had been a reaction to the Commonwealth, with this trend being reflected in the theatre as well.

The 18th Century saw the succession of several monarchs. After the co-reign of William and Mary, Queen Anne took the throne and reigned from 1702 until 1714, during which time Parliament gained more power. The following king would be a German prince, crowned as George I. He was the first of the house of Hanover… and spoke no English, which meant he left most of the ruling to the Parliament and specifically to Sir Robert Walpole (1676-1745). George I reigned until 1727 and was followed by his son, George II, who ruled in the same way until 1760. George III reigned for the rest of the century, witnessing and playing a significant part in some of the most important events of the century, such as the addition of Canada and Australia to the British colonies, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution.

When it comes to theatre, one of the most influential political actions of the time was the Licensing Act of 1734, which was enforced by the Parliament and that in many ways determined the fortunes and misfortunes of both theatre companies and playwrights by defining the tone and subject that could be developed into plays and by reiterating that only licensed companies could legally stay in business. Considering that there were only two companies that were granted the license (the Drury Lane and the Covent Garden), the number of plays that was needed decreased significantly.

The Licensing Act of 1734

The Licensing Act of 1734 was instituted by the British Parliament under the direct supervision of the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole.

It basically established government censorship over any theatrical piece, as it appointed an Examiner who was to read and evaluate all the plays seeking to receive a license. The examiner would then proceed to present the plays with his recommendation for licensing to the Lord Chamberlain, who ultimately would grant or deny the license. All licensed plays would be included in the Lord Chamberlain’s collection, which is now available at the British Library.

The Examiner was also tasked to visit the licensed theatres in order to make sure that the material was produced as it had been approved by the Lord Chamberlain.

While some form of government supervision had been in place previously during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the Licensing Act of 1734 exercised a stronger grip on theatre, mostly to shush political criticism and political satire.

The Licensing Act of 1734 was repealed by the Theatre Act of 1843.

The first half of the 1700s saw genres following more conventional and socially accepted themes. For comedies, there is a significant shift towards sentimentalism and the re-establishment of morals. Two playwrights who championed this trend were George Farquhar (1678-1707) and Colley Cibber (1671-1757). Farquhar’s style is a direct evolution of Congreve’s, with the attention being on the characters’ moral journey. Cibber instead focused on complex plots that generated a variety of obstacles to the characters and that culminated with a somewhat unearned resolution and happy ending. A slight shift in the genre is provided by Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729). While still heavily relying on sentimentalism, Steele moves the action to his contemporary days and locations and gives voice to middle-class or lower-class characters, who, because of their virtuosity, after going through a series of adversities, are socially and economically rewarded.

Later in the century, the sentimentalist trend fades away and playwrights embrace a more immediate style of comedy, often referred to as the “laughing comedy”. Masters of this style are Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) and Oliver Goldsmith (1730-2794).

Goldsmith is remembered for the play She Stoops to Conquer, which is still very popular today. The comedy banks on all possible comedic devices, including mistaken identities, misunderstandings, violation of social hierarchy, trickery, and bawdy, everyday language. Sheridan tended to abide by more uplifting and morally satisfying plots and characters, his strengths being a great use of wit through the characters’ dialogue, language in general, and an outstanding portrayal of the English society of the time.

Tragedies and other forms of theatre

Other forms of theatre didn’t disappear during the 18th Century, although comedies still won the popularity contest.

For the entire century, tragedies also rode the sentimentalist vibe, mostly relying on “underdog” characters or pathetic heroes/heroines. Characters more and more represented the middle and working classes rather than the upper class and the nobles, in an attempt to make the plays more relatable for the audience. Tragedies were still tasked to carry an educational message; therefore, some playwrights – most notably George Lillo (1693-1739)- believed that it was imperative to craft stories that were closer to the audience.

Because of the Licensing Act of 1734, genres that didn’t (or wouldn’t) fall directly under the category of “theatrical performances” gained popularity, as they could be performed by unlicensed companies in unlicensed spaces. This determined the rise of the popularity of pantomimes and the Ballad Opera.

English pantomime is an evolution of Commedia dell’Arte as experienced by the English through the work of the Italian touring troupes. A good representation of it is given by the work of John Rich (1692- 1761), whose pantomimes often revolved around typical commedia stock characters, such as Arlequin.

Ballad Opera echoed the popularity and the style of the Italian Opera Buffa. The most famous ballad opera is certainly John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera – which will later become the inspiration for Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera (1928). The greatest difference between the Italian Opera Buffa and Gay’s Ballad Opera is the greater use of dialogue between popular melodies and the depiction of middle and lower class characters rather than upper class ones.

The end of the 18th Century will mostly see English theatre steer towards melodrama, which will constitute a major player in the following century.

Theatrical Spaces

During the Restoration, theatrical buildings in England, and specifically in London, blended some of the elements of the Elizabethan theatre with those of the Italian style theatre.

The most famous theatres of the time were the Drury Lane, Lincoln’s Inn (which was a converted tennis court), and the Dorset Garden.

The biggest difference between these theaters and those used during Elizabethan times was that open-air theatres gradually disappeared in favor of indoor spaces. The proscenium arch was consistently implemented, perspective painting was applied to the scenery, and the stage and the house floors were raked to allow better sightlines for the audience. The stage was divided into two parts by the proscenium arch, a downstage one (towards the audience) called the apron, and an upstage one that was used almost exclusively for the scenic design. The apron was the area where the actors would be performing, and it was very deep. On its sides, two to four doors opened (one or two doors on each side) to the stage, and at times, there would be balconies above the doors. The doors were used for the entrances and exits of the actors, while the balconies added options for levels and “special appearances”.

The upstage area was also very deep to accommodate the scenery. Differently from what was happening in continental Europe, England did not implement Torelli’s pole-and-chariot system and preferred to use the “grove system”, where the painted flats were stacked in front of one another. Stagehands and crew would operate them so that when a scene change needed to happen, the flats would be pulled into the wings, revealing new ones on stage.

Because the scenic needs of the theatrical pieces of the time were quite similar, all the painted wings, flats, and shutters represented standard places, such as the garden and the drawing room, and were utilized for all plays according to need.

As for the seating area, there were three distinct areas: the pit, close to the stage, boxes, and galleries. The pit was now furnished with wooden benches, so the audience was able to sit.

Over the 18th Century, English theatres found a more balanced compromise between the depth of the apron and the upstage area of the stage: the apron became narrower while the area behind the proscenium arch started to become a shared space for scenery and acting. This new arrangement of the space implies that the side doors to the apron have been reduced from four to two, one on each side.

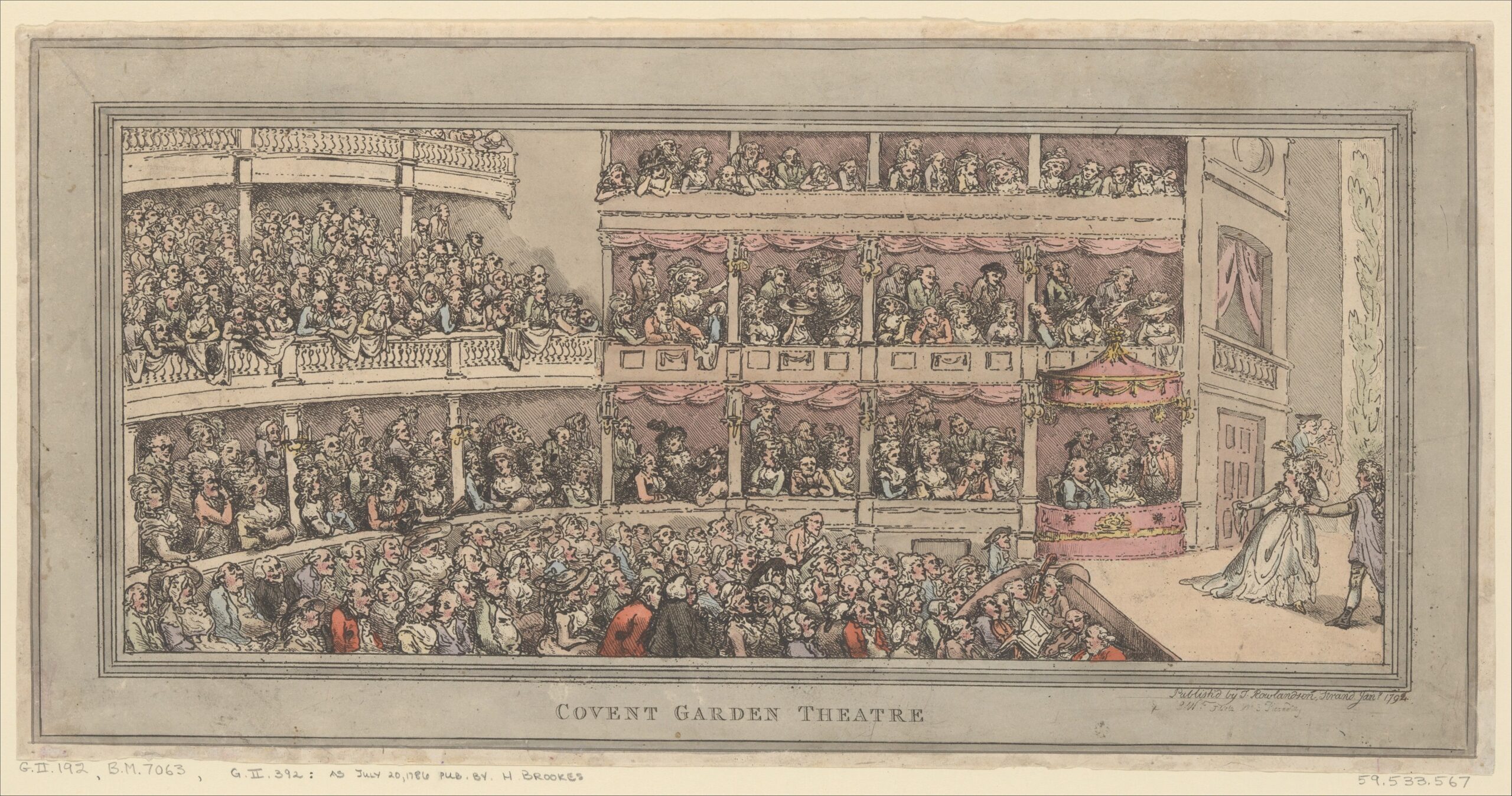

Because the Drury Lane and the Lincoln’s Inn were the only two official/legitimate (aka, licensed) theatres in London, they underwent several renovations to accommodate a wider audience, as originally they were both fairly small, seating around 600 people.

For example, as the Covent Garden theatre replaced Lincoln’s Inn in 1732, it was designed to seat around 1,400 people. Later in 1784, it underwent a renovation that brought the house to seat 2,500 people, and finally, in 1792, the theatre was completely redesigned and built to accommodate 3,000 people.

CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

TAKEAWAYS

Charles II restored the monarchy and reopened theatres.

Both theatres and theatre companies needed to receive the royal license to legally be allowed to work.

The only two legal companies were William Davenant’s and Thomas Killigrew’s ones and they resided in the Drury Lane and the Lincoln’s Inn Theatres.

Women were allowed to act.

The acting style was still non-realistic, although some attempts at greater realism were pursued by a few actors, such as Nell Gwyn, Charles Mackin, and David Garrick.

Theatre companies abandoned the sharing plan in favor of a contract system.

The most popular genre of the Restoration and the 18th Century was comedy.

Restoration comedies set themselves apart for their bawdiness and explicit sexual content.

The most popular playwrights of the Restoration are Wycherley and Congreve.

During the second half of the 18th Century, both comedies and tragedies tended to become more sentimental, up until the works of Sheridan and Goldsmith at the very end of the century.

Tragedies were not exceedingly popular.

Pantomime and Ballad Operas reflected the influence of Italian touring troupes.

The Licensing Act of 1734 marked a significant shift in the trajectory of plays and the theatre in general.

Theatrical spaces became exclusively indoor and somewhat merged features of the Elizabethan theatres and of the Italian style theatres.

While perspective drawing was introduced in scenery, English Theatres still relied on the grove system rather than on Torelli’s chariot-and-pole system for scene changes.

Actor and theatre manager David Garrick could be considered one of the early fathers of modern theatre directing.

Vocabulary

King Charles I

Oliver Cromwell

First English Civil War

The New Model Army

Commonwealth

King Charles II

Restoration

William Davenant

Thomas Killigrew

Drury Lane Theatre

Lincoln’s Inn Theatre

Covent Garden Theatre

Boy players

Edward Kynaston

Benefit performances

Charles Macklin

Pantomime

Ballad Opera

Statute of Anne

Nell Gwyn

David Garrick

Aphra Behn

John Dryden

Sir George Etherege

William Congreve

William Wycherley

The Country Wife

The Way of the World

The Rover

The Licensing Act of 1734

Sir Robert Walpole

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Oliver Goldsmith

She Stoops to Conquer

John Gay – The Beggar’s Opera

Apron

Grove system

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

This activity focuses on better understanding the topics and the themes of Restoration theatre in England, and it should be done after the instructor has introduced the period.

The instructor should divide the students into small groups (3 to 4 students per group).

Each group should be assigned a theme to research and further develop.

Examples include: a playwright, the advent of female actors, the changes in theatre design and architecture, the changes in costume design, the political and social satire embedded in the plays, and the nature of the audience.

Groups should be given access to the internet to do some in-class research and should prepare a 5-minute presentation about their assigned topic, which should include a grounding in history, such as some historical facts that might have influenced (and how) that particular topic/development in theatre.

Each group should also reference some source material OTHER than the textbook (or Wikipedia). The instructor should be available for consultation about possible sources.

Finally, each group should investigate and provide a supported opinion on whether and what still resonates in modern platforms that might be similar or derived from the Restoration style.

Each group should present its work to the class.

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 1603 | Death of Queen Elizabeth I | Ends the Tudor dynasty; James VI of Scotland becomes James I of England, beginning the Stuart reign. |

| 1625 | King Charles I* becomes King* | Advocates of divine right monarchy; his reign led to tensions with Parliament, eventually impacting the theatre. |

| 1642 | *Start of *First English Civil War | Conflict between Royalists and Parliament’s New Model Army; all public theaters are officially closed. |

| 1649 | *Execution of Charles I; establishment of the *Commonwealth | Theatre is outlawed under Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan rule; underground performances begin. |

| 1650s | William Davenant stages musical dramas secretly | Uses his home for performances; he evades restrictions by framing plays as concerts. |

| 1658 | Death of Cromwell; brief rule of son Richard | Political instability leads to calls for monarchy restoration. |

| 1660 | Restoration of the monarchy under Charles II | Theatres re-open; royal support rejuvenates theatrical culture. |

| 1660s | William Davenant and Thomas Killigrew granted patents | Exclusive legal control over the theater in London; establish Drury Lane Theatre and Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre. |

| 1662 | Women are allowed on stage | A milestone; boy players begin to phase out; Edward Kynaston is a notable exception who adapts. |

| 1660s–1670s | Nell Gwyn becomes a celebrated actress | Former orange seller becomes stage star and mistress to Charles II. |

| 1660s–1680s | Growth of satire and audience interaction | Restoration theatres reflect class divides (pit, boxes, galleries); social satire aimed at the aristocracy resonates with audiences. |

| 1660s–1690s | Rise of Comedy of Manners | Witty, satirical comedies emerge that mock aristocratic behaviors and social norms; key playwrights include Wycherley, Etherege, and later Congreve. |

| 1670s | Rise of benefit performances | Actors receive proceeds from designated shows; introduced contractual compensation. |

| 1675 | Premiere of The Country Wife by William Wycherley | Exemplifies bawdy, satirical Restoration comedy. |

| 1677 | All for Love by John Dryden | Signals the emergence of neoclassical tragedy influenced by Shakespeare. |

| 1679–1689 | The work of Aphra Behn gains prominence | One of the first professional female playwrights, author of The Rover, known for strong female leads. |

| 1688 | Glorious Revolution: William and Mary ascend | Ends the Restoration era politically; begins a shift in theatrical themes. |

| 1700 | The Way of the World by William Congreve | Peak of Restoration comedy; signals transition to sentimental drama. |

| 1702–1714 | Reign of Queen Anne | Parliament’s power expands; theater licensing becomes stricter. |

| 1709 | Passage of the Statute of Anne | First law protecting authors’ rights; impacts playwright ownership. |

| 1714 | Accession of George I (Hanoverian dynasty) | The theater was influenced by Parliament; Sir Robert Walpole became de facto ruler. |

| 1734 (enforced 1737) | Licensing Act enforced | Censorship of plays begins; only Drury Lane and Covent Garden Theatre are licensed to perform. |

| 1730s–1760s | Sentimental comedy dominates | Writers like Colley Cibber, George Farquhar, and Sir Richard Steele focus on moral themes and virtue. |

| 1740s–1770s | The career of David Garrick flourishes | Reforms acting and rehearsal processes; promotes historical costuming and realism; revitalizes Drury Lane Theatre. |

| 1760s–1770s | Charles Macklin innovates realistic acting | Especially known for portraying Shylock in Merchant of Venice without caricature. |

| 1769 | Shakespeare Jubilee hosted by Garrick | Celebrates Shakespeare’s legacy; solidifies him as the national poet. |

| 1773 | She Stoops to Conquer by Oliver Goldsmith | Embraces “laughing comedy,” contrasting sentimentalism. |

| 1777 | The School for Scandal by Richard Brinsley Sheridan | Classic example of wit and social satire in late 18th-century theatre. |

| 1728 | The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay premieres | Launches the Ballad Opera genre; critiques society using popular tunes and dialogue. |

| Mid–late 1700s | Pantomime and Ballad Opera gained popularity | Unlicensed genres thrive under the restrictions of the Licensing Act. |

| Mid–late 1700s | Rise of the middle class | Theater content begins to reflect middle-class values, especially in comedy and sentimental tragedy. |

| Late 1700s | Enlightenment ideals influence theatre | Focus on reason, character development, and individual agency shapes dramatic storytelling. |

| Late 1700s | Expansion of printed texts | Increased access to plays and actor memoirs builds celebrity culture and spreads theatrical tastes. |

| 18th century | Shift to indoor theaters; architectural change | Use of apron stages, grove system for scenery; larger auditoriums, e.g., Covent Garden Theatre, rebuilt multiple times to expand capacity. |