6 Chapter Six – The Spanish Renaissance

CHAPTER 6 – The Spanish Renaissance

The Renaissance in Spain, also referred to as the Golden Age (El Siglo de Oro), covers about one hundred years at the end of the 16th Century. It coincides with the affirmation of the Spanish monarchy over the country, after the Moors, who had been ruling most of what is now Spain for over seven hundred years- were definitively defeated and Catholicism was established as the only religion of the country.

While Spain was under the Moor hegemony, theatrical activities were banned.

In 1469, King Fernando of Aragon married Queen Isabella of Castile and Leon, and this marriage assured them control over the whole country. In 1478, they instituted the Inquisition, a tribunal that was designed to persecute heresy and provide strong, absolute grounds for Catholicism. Anyone who didn’t convert to the state religion would be banned, and that was the best-case scenario, as torture and executions were the Inquisition’s common practice. By the end of the 16th Century, the Moors and the Jews were forced out of the country in a diaspora.

Spain gained an extraordinary political power with the new monarchs. In 1592, a Spanish expedition captained by Christopher Columbus led to the discovery of a new continent. After that, Spain slowly -and violently- established its hegemony in the Americas as a colonizer while affirming its political power in Europe as well, at least up until 1588, when the Spanish Armada was defeated at sea by the English navy.

When it comes to the arts, and theatre specifically, the Spanish Golden Age produced an incredibly high amount of plays, both religious and secular. It has been calculated that the number of plays written in Spain before the 18th Century is between 10,000 and 30,000!

Clearly, not all of those have survived, and only a fraction of those that have survived are still worth mentioning and producing today, but still, that is an incredible patrimony that by far exceeds what happened in other countries for the same period.

The early Spanish Renaissance, starting at the beginning of the 16th Century, marks the definition, development, and affirmation of the autos sacramentales, one-act (autos) religious plays that, while reminiscing the Medieval morality plays in some ways, also feature unique elements that speak to the Spanish cultural environment of the time.

These plays were performed for the Corpus Christi festival, first in Valladolid (the first capital of Spain) and then in Madrid.

The autos were extremely popular, and once they had been performed at the festival, they would tour the country. They focused on allegories, emphasizing morals and good Christian behavior. They had an almost fairy-tale-like structure, with characters that were not all necessarily “human” but would rather embody a vice, a virtue, death, justice, beauty, and so on. The ending established the triumph of good over evil and celebrated the birth of Jesus Christ.

The autos would be performed at the beginning of the festival, after the opening procession was over. The troupes had two very ornate wagons, called carros, that functioned as a sort of tiring house, providing scenery and allowing for costume changes. The carros could be up to two stories high, and they were made of wood. Some of the most sophisticated ones had machinery that allowed for “special effects”, such as flying an actor on and off the stage. A third carro was utilized as the stage, and typically “bridged” the other two wagons.

To add to the spectacle, actors wore impressive costumes, although those costumes were not “period”, but rather reflected the fashion of the time.

Autos sacramentales were controlled and produced by the City Council, who would then appoint and pay a professional theatre company to stage them. The demand for autos sacramentales was so high that virtually every Spanish dramatist had written several. All of the most well-known playwrights, such as Lope de Vega, Cervantes, and Calderon de la Barca, made a good living out of these plays.

When it comes to non-religious (secular) drama, it has to be said that there was a strong influence coming from Italian Commedia dell’Arte touring troupes, which were extremely popular all over continental Europe in the first half of the 16th Century and onward. In a way, those troupes set the tone for a non-religious style of performance.

Secular plays were called comedias. While it is true that the most successful ones were on the lighter side with happy endings, the term also applies to tragedies.

Comedias usually had three acts, did not follow the Aristotelian unities, and could be divided into “cape and sword” plays—with chivalric characters and a romantic underlying tone— pastoral plays, mythological plays, and machine plays, plays that need a deus-ex-machina effect to achieve their resolution.

The most popular themes for secular plays were love, honor, historical storytelling, and patriotism. Playwrights often shifted the tone within each play, so that there was always some form of comedic relief for the audience.

Plays were written in verse, although the Spanish language doesn’t have an English Blank verse equivalent when it comes to meter. The ability of each playwright determined the elegance of the verse, with Lope de Vega being considered one of the best writers ever to use verse.

As a general rule, plays were very respectful of the Church, although taking liberties was not completely out of the question, and were not always persecuted, although censorship existed and was widely exercised.

Until 1587, female roles were played by men. However, soon after it became possible for women to act on stage, provided that their husbands were in the theatre troupe and that there was no cross-dressing.

1631 marks the birth of the Spanish professional acting guild, the Confadia de la Novena, which is still in existence today and has come to include all theatre artists.

By the mid 1650s theatre companies would have up to twenty actors on roster, along with a healthy crew working backstage, including apprentices, wardrobe crew, stage hands, money collector and, of course, a prompter – as the number of plays that each company had to keep in repertoire was such that made it challenging for actors to be fully memorized. A glimpse into the actors’ daily life is provided by a published work of the early 1600s, titled Entertaining Journey, and written by a contemporary actor of the time, Rojas Villandrando. It states that actors had an extremely tiring and full day, starting as early as 2 am for line memorization, and then would go into rehearsals at around noon for a 2 pm performance. Sometimes an afternoon performance followed, and then yet another early-evening show would go well into the night!

Professional theatre troupes needed to obtain a license from the Royal Council to be allowed to perform or to commission work.

There were two kinds of professional theatre companies. Some were very similar to the Elizabethan cooperatives, with actors being shareholders, managers, producers, and playwrights who occasionally hired other actors for lesser roles. Then, there were companies that were directed by a manager, who was in charge of hiring the actors along with everyone else, usually under two to three-year contracts.

By the first half of the 17th Century, there were twelve licensed companies in Spain, and all of them could operate in theatres (corrales) or the Corpus Christi festival.

Along with the professional companies, there were several Italian Commedia dell’Arte touring companies.

Initially, all theatrical activities had to take place on Sundays or major holidays, but that changed after 1580, allowing for daily performances and more structured theatrical seasons. During Lent, no theatrical activity was allowed.

FUN FACT

The Spanish equivalent of the Elizabethan groundlings were the mosqueteros, who usually attended performances in the patio. It has been recorded that mosqueteros could use whistles, rattles, and other noise-making devices to manifest their distaste for the production. Similarly, women were known to throw fruit and vegetables at the actors!

Theatrical Spaces

We mentioned how autos sacramentales were performed on wagons, and how that allowed the companies to tour and be part of the procession for the Corpus Christi. This was vastly different from secular plays, as a more structured theatrical space was needed.

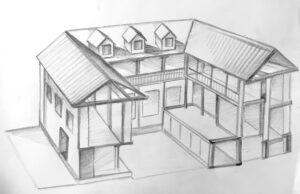

The typical space for professional production would be a corrales (a theatre), which in many ways resembled the Elizabethan public playhouse.

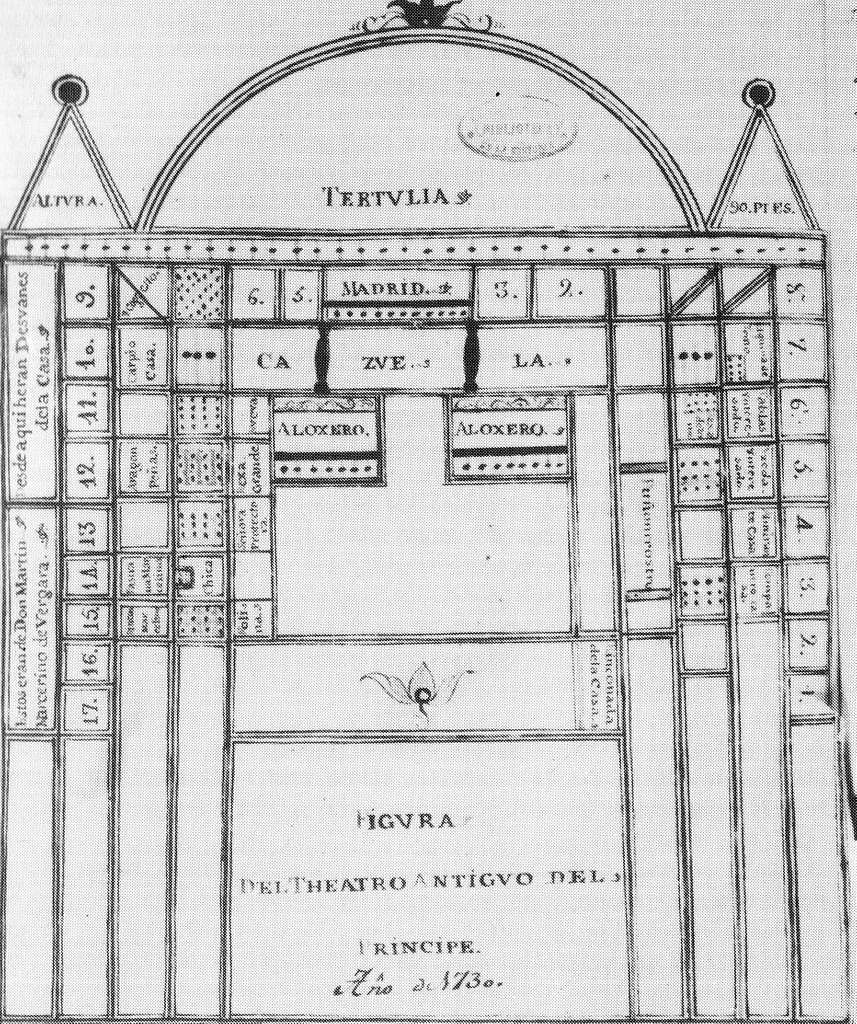

These buildings featured a combination of outdoor and indoor spaces, and were built around a square or rectangular courtyard. They featured an open-air (unroofed) pit (a patio), as well as several roofed seating areas in the galleries on the side. Boxes were also available. While the first known theatre was built in the city of Seville, the two most important ones were (of course) in Madrid, the Corral de la Cruz, built in 1579, and the Corral del Principe, which was built slightly later, in 1583.

The stage (encenario) was an elevated wooden platform, opposite to the entrance of the theatre, that featured several trapdoors and a multi-floored tiring house (vestuario) at its back.

Admission to the patio was quite inexpensive, and that is where the loudest of the audience would be. Closer to the stage, there were a couple of rows of benches – called taburetes – where the most notable citizens would sit. At the side of the patio, there would be wooden risers, called gradas, which provided roofed seating, above which you had two to three orders of galleries with boxes. The upper level was immediately underneath the roof, making for quite a claustrophobic space called desvanes.

The admission ticket price would change depending on the location in the house, the cheapest seats being in the patio and in the desvanes, followed by the gradas, and the boxes.

Opposite the stage, by the entrance of the theatre, there would be a concession booth (alojeria), above which there would be a gallery for unaccompanied women, called cazuela. Regulations strictly prohibited men from accessing the cazuela and solo women from walking into the patio. Of course, women could sit (or stand) in other areas of the theatre if they were accompanied by their spouses.

Above the cazuelas there could be an additional two orders of galleries with boxes for city officials and personalities.

The Corrales would seat between 1000 and 2000 people at the peak of their activity, around 1630.

The tiring house featured three different levels that were accessible to the actors from backstage through staircases. As for the Elizabethan theatre, scenic design elements were not much needed, as locations and scene descriptions were being embedded in the text or the actions of the actors.

The tiring house would provide a backdrop for the entirety of the play, with the occasional addition of curtains to facilitate “surprises” of some sort. The ground floor of the tiring house had three doors, the central one being the biggest one.

The upper levels had windows overlooking the stage. Those could be used for specific needs in a scene, to drop a curtain, or for the actor to have “discoveries.”

Some scripts required more complex backdrops and scenic pieces – potentially to showcase different locations. In that case, side structures were installed, functioning like the side wagons of a Medieval mansion.

Playwrights

It is believed that the first Spanish theatre artist who could be considered a professional in the field was Lope de Rueda (1510-1565), who started off his career as an actor and gained almost instant success at court, which secured him several appointments at the Corpus Christi Festival in Madrid. He is also credited for authoring several full-length and short plays, including Armelina, The Olives, and The Mask. He was most successful at writing comedic scenes and dialogue, and used characters such as fools and scoundrels – characters he also usually played himself.

Miguel Cervantes (1547-1616) is also an active playwright of this time, although he is mostly remembered for his novel, Don Quixote. He wrote several comedias, only a few of which have survived. His style was more learned and tended to a more aristocratic audience.

The two most important playwrights of this time, by a long shot, are Lope de Vega and Calderon de la Barca.

Lope Felix de Vega Carpio (1652-1635) wrote compulsively on top of an otherwise very active and adventurous life. He bragged about writing over 1500 plays in his lifetime. More realistically, he wrote about 800, and a little more than half of them survived.

He was from a middle-class family and was set to become a priest, until he left the Jesuit University to join the Spanish Armada. He worked for several noblemen, had several love affairs, married twice, and finally was ordained as a priest.

Aside from plays, he also wrote poems and other forms of literature.

Stylistically, his plays are written in elegant verse, using compelling and natural dialogue.

He was mostly famous for his comedies, although he wrote tragedies as well. He sourced his plots from almost anything: from Italian novellas and mythology to pastorals and chronicles. He is praised for his strong defining action that determines a tense rising action, as well as his female characters. Most of his plays had large casts of characters, quite similar to what happened in the English Elizabethan theatre.

Amongst his plays, it is worth mentioning The Sheep Well, a pastoral play, The Dog in the Manger, a “cape and sword” play, and The Foolish Lady, a romantic comedy with a few twists.

He was the most revered playwright of his time, in Spain and beyond. Felipe III appointed him as the director of the Court Theatre in Madrid, a position he held until his death. His plays were translated into several languages and had a profound impact on German Romantic writers of the 19th Century.

Pedro Calderon de La Barca (1600-1681) lived in the shadow of Lope de Vega’s popularity until his death, when he then rose as Spain’s most popular playwright.

He became a priest and he first authored autos for the Corpus Christi Festival in Madrid, gaining popularity at court. He started writing secular plays after 1622, and it is believed that he wrote about two hundred plays, out of which about half survived (mostly autos). His secular plays revolve around love and honor, “cape and sword” style.

Titles include The Phantom Lady, a romantic play based on misunderstandings, The Physician of His Own Honor, revolving around a physician who kills his wife because he suspects of her cheating on him, and his masterpiece: Life is a Dream, which is one of the most popular Spanish plays of all time, scoring several productions each year all around the world.

In Life is a Dream, the prince Sigismundo is locked up in a tower to prevent the prophecy that would see him committing terrible crimes. His father, King Basilio, feels remorse and sets him free, hoping to prove the prophecy wrong. Yet, Sigismundo does indeed commit several violent crimes, forcing King Basilio to sedate him and lock him back up. When he wakes, Sigismundo wonders if all that had happened was real or just a dream. As political turmoil sets in and turns into a civil war, Sigismundo is set free by the rebels. When the rebels get the upper hand in battle, he faces his father one more time. King Basilio is prepared to die, but Sigismundo spares him, which leads Basilio to abdicate in his favor. From that moment on, Sigismundo swears to act “God to God”, meaning that he will only strive for goodness.

Below you can read Sigismundo’s monologue at the end of Act 2, where he muses about life, the human condition, and reality. It is one of the most famous monologues of all time.

“I must control this savagery,

This wild ambition, this ferocity

Of mine in case I dream again.

For surely I’ll dream again

When this world seems so a strange place

That all our life is but a dream,

And what I have seen so far tells me

That any man who lives dreams what

He is, until, at last, he wakes.

The King dreams he is king, and so

Believing rules, administers,

Rejoices in the exercise of power;

He does not seem to know his fame

Is written on the wind and death

Will turn to ashes all his splendour.

O who would want to be a king

And have his power, when the dream

Of death must soon awaken him?

The rich man dreams in all his wealth,

Though riches cause him endless care.

The pauper dreams his suffering,

Complaining that the world’s not fair.

The man who has success dreams too,

And so does he who strives for more.

He dreams whose heart is full of spite,

Who, hurting others, claims he’s right.

The world, in short, is where men dream

The different parts that they are playing,

And no one stops to know their meaning.

I dream that I am here, a prisoner,

I dream that I am bound by chains,

When once I dreamt of palaces

Where I was king, where once I reigned.

What is this life? A fantasy?

A prize we seek so eagerly

That proves to be illusory?

I think that life is but a dream,

And even dreams not what they seem.

It’s important to mention the other two playwrights of the time: Guillen de Castro and Tirso de Molina.

Guillen de Castro (1569-1631) is remembered for his play The Youthful Adventures of the Cid, which will greatly influence Corneille’s Le Cid.

Tirso de Molina (1584-1648) was very prolific, writing over 400 comedias of a variety of subjects and genres. He did not shy away from discussing political matters in his plays, which stirred some controversy and led him to be exiled from Madrid. He wrote some of the most compelling female characters of his time. His most famous play, The Trickster of Seville, was the first ever play to deal with the character of Don Juan.

TAKEAWAYS

EL Siglo de Oro (The Spanish Golden Age) produced the greatest number of plays of the Renaissance.

Plays were either an evolution of Medieval morality plays, with a religious intent (the autos sacramentales), or were secular (comedias).

Plays were written in verse, although meter was not defined.

Aristotelian unities were not followed.

Women were allowed to act.

Italian Commedia dell’Arte traveling troupes were very popular in Spain and influenced Spanish secular plays in terms of themes and style.

All playwrights wrote both kinds of plays.

Autos sacramentales were performed as part of the Corpus Christi festival.

Theatre troupes would travel and needed to be licensed.

Professional theatre troupes worked under a shareholding system or were managed by a director.

The Spanish professional theatre guild was called Confadia de la Novena, and was instituted in 1630.

The most important playwrights of the time were Lope de Vega and Calderon de la Barca.

Autos sacramentales would be performed on carros (wagons), while comedias were performed in corrales, theatrical spaces that had similar features to the Elizabethan public playhouse.

ACTIVITY FOR THE CLASSROOM

The instructor should assign the class to read Tirso de Molina’s The Trickster of Seville, and then students should be divided into small groups – 4 students per group max.

Each group will research the evolution of the character of Don Juan and prepare a short (10 minutes) presentation on a later version of the story and of the character.

Students should provide a historical comparison and a style comparison.

All forms of media could be included in the research. Actually, the more the merrier!

Examples could include novels, other plays (modern or contemporary), adaptations, movies, TV shows/series, comic books, etc.

Each presentation should provide an examination of the similarities with the original material and character, a historical and artistic background, and an excerpt from the “new” material.

Vocabulary

El Siglo De Oro

Inquisition

Spanish Armada

Autos sacramentales

Corpus Christi

Carros

Comedias

“cape and sword”

Pastoral plays

Mythological plays

Machine plays

Confadia de la Novena

Royal Council

Corrales

Mosqueteros

Patio

Corral de la Cruz

Corral del Principe

Encenario

Vestuario

Taburetes

Gradas

Desvanes

Alojeria

Cazuela

Lope de Rueda

Miguel Cervantes

Lope de Vega

Calderon de la Barca

Life is a Dream

Guillen de Castro

Tirso de Molina

| Time Period | Event | Significance |

| 1478 | Establishment of the Spanish Inquisition | Political and religious control deeply impacts themes in Spanish art and theatre. |

| 1492 | Expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain | Marks the beginning of a highly Catholic, centralized Spanish monarchy. |

| 1500s | Early development of religious drama (Autos sacramentales) | These allegorical plays tied to Catholic doctrine were performed during Corpus Christi festivals. |

| 1558-1561 | Lope de Rueda tours Spain | Often seen as the founder of Spanish professional theatre, he wrote and performed simple farces and pasos. |

| 1579 | Opening of the Corral de la Cruz in Madrid | One of the first permanent theatres (corrales), an open-air courtyard theatre. |

| 1583 | Corral del Príncipe opens | Another major corral in Madrid advances the urban theatre scene. |

| 1588 | Defeat of the Spanish Armada | Marks the decline of Spanish naval dominance but not its cultural influence. |

| 1590s | Emergence of comedias and capa y espada (“cape and sword”) plays | Popular three-act plays blend honor, love, and action. |

| 1598 | The reign of Philip III begins | Court support for the arts increases during this period. |

| 1600s | Tirso de Molina writes ‘The Trickster of Seville’ | Introduces Don Juan, a legendary figure in Western drama. |

| 1605 | Miguel de Cervantes publishes Part I of ‘Don Quixote’ | A landmark literary work that also critiques theatre and chivalric ideals. |

| 1610s | Rise of Lope de Vega | Called the ‘Phoenix of Wits’, he wrote over 1,000 comedias and helped shape the three-act structure. |

| 1605-1615 | Guillen de Castro writes ‘Las Mocedades del Cid’ | Source material for Corneille’s famous French adaptation. |